Wizards is a film that only seems to make some kind of logical sense when viewed as part of a Ralph Bakshi marathon. Placed in context within his body of work, sandwiched between the radically cartoonish, venomously indignant Coonskin (1975) and the rotoscoped, literate, epic fantasy The Lord of the Rings (1978), Wizards feels like a natural transitional work, a fantasy with elements of both films knitted into its DNA. I believe that Coonskin and LOTR are better pictures, though each are flawed. Nevertheless, Wizards is undeniably fascinating, a film that could be made in no other year: psychedelic, violent, sexy, political, eager to offend, and yet a “children’s film” (Bakshi’s words) rated PG presumably because it has elves and fairies in it.

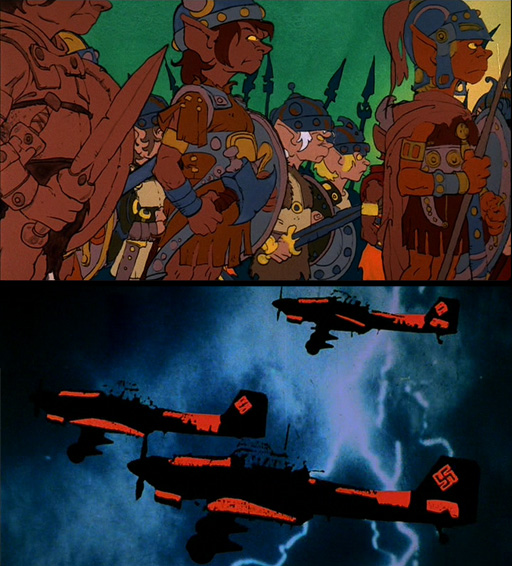

Technically, the film is actually science fiction. An introduction explains this through live-action footage that segues into illustrations drawn by comic book artist Mike Ploog and narrated by Susan Tyrrell (Forbidden Zone‘s Queen of the Sixth Dimension, and the voice of Juliana in Bakshi’s later fantasy Fire and Ice). Wizards takes place in a post-apocalyptic Earth thousands of years in the future, in which man is extinct through nuclear war, and new races have taken dominion. Avatar (Bob Holt) and Blackwolf (Steve Gravers) are twins born from the Queen of the Fairies, though Blackwolf is born disfigured, with skeletal arms and bulging eyes. Both have inexplicable magical powers, which Avatar uses for good and Blackwolf for evil. When their mother dies, never having recovered from their difficult birth, the two brothers duel for rights to rule in her seat over the kingdom of Montagar. Avatar wins, and Blackwolf retreats into the desolate land of Scortch. As the film begins (“3000 years later”), it is in his exile that Blackwolf uncovers Nazi war propaganda, as well as tanks, planes, and guns, and leads an army of goblins and demons against the peaceful inhabitants of Montagar.

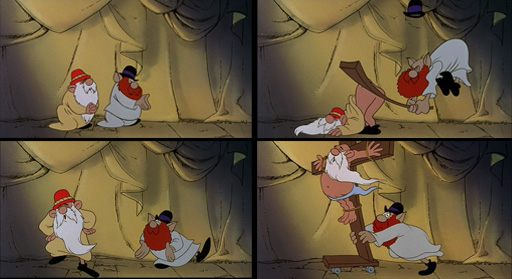

The theme of the film is explicitly stated at the film’s outset: “An illuminating history bearing on the everlasting struggle for world supremacy fought between the powers of technology and magic,” as Tyrrell reads to us off a memorial standing erect upon a parched earth. So aging, weary, cigar-chomping wizard Avatar reluctantly sets out on a quest to destroy his brother once and for all, joined by a hot-tempered young warrior, Weehawk (Richard Romanus), a large-breasted fairy, Elinore (Jesse Welles), and an amnesiac assassin who was once their enemy (David Proval). But Bakshi seems uncomfortable, or at least disinterested, in a traditional quest narrative. He likes to cut away to vignettes of a style closer to his earlier, adult animated films: semi-improvised dialogue, featuring different characters who appear nowhere else in the film, delivering comedy bits wedded to sometimes crude, sometimes interesting social comment. Such as a scene in which two gas-mask-wearing soldiers in Blackwolf’s army bicker about the horrors of war before one accidentally shoots the other mid-argument, or an interminable bit as two local priests engage in an elaborate pantomime while praying to God for guidance.

This particular sequence can be taken one of two ways. (1) Bakshi is saying “religion is silly and stupid,” which is hardly incisive satire. (2) Bakshi is saying “religion is silly and stupid” in a film marketed toward young audiences, which is something more remarkable. So although the trailer is eager to tell us that the movie is like “Tolkien,” the film’s author is clearly Bakshi, happy to lob bombs wherever he can.

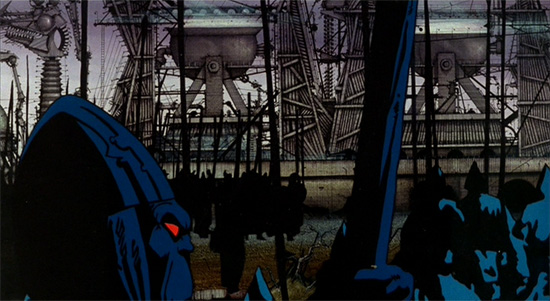

Meanwhile, interludes in Scortch show Bakshi developing a new technique to save time and money in his animation. In their book Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi, authors Jon M. Gibson and Chris McDonnell describe how the process was accomplished: by feeding 35mm film taken from Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky (and other war pictures and newsreels) through new-to-the-market photocopy machines. This process resulted in “high-contrast graphical shapes on long spools of paper that had to be manually cut, aligned, pasted onto punched animation paper in just the right location, and finally photocopied onto cels in order to work.” The result is oddly haunting, mainly because it looks so weird. It is quite evident that one is seeing live action footage incorporated into the animation, however, and leaning on this technique too heavily kills the effect. It happens in Lord of the Rings, and it happens in Wizards. (Bakshi had been blending the two worlds in one way or another ever since Fritz the Cat, and this aesthetic reached its height in the semi-autobiographical Heavy Traffic. Bakshi would never again integrate live action footage and cartoon characters with such resonance.)

There are some traditional fantasy sequences of the 70’s sword-and-sorcery variety (the genre was in vogue): the heroes encounter some wicked fairies, battle a monster, and briefly Avatar and Elinore are exiled through sorcery into a vast and snowy wilderness. But Bakshi hadn’t yet learned how to sustain a traditional narrative; it sometimes feels like more of a cartoonist’s sketchbook than a proper movie. Indeed, like many of his films, there are individual sequences in Wizards which are fantastic, and perhaps the film holds up best when limited to brief clips posted online. Or viewed under the influence of certain substances (legally obtained, of course)…which, to be sure, helped make it a midnight movie staple in the first place.

I’ve revisited this picture several times, usually leaving with a certain amount of frustration. I saw it as a child, when the film was completely indigestible to me. Cartoon characters swearing and shooting bloody holes in one another? What was this? I watched it a few times as a teenager, and as a college student reacted to the film by drawing my own psychedelic sword-and-sorcery comic book satire, as a creative reaction, but also determined that I knew how this sort of thing really ought to be done. Now I’ve owned the DVD for some years and occasionally will still watch it, just recently to see how it would look on a big-screen TV, for a more “theatrical” experience. The film is still what it is. Beautiful, ugly, radical, messy. It is, at the least, an experiment in stretching both animation and genre out of their traditional boundaries, and for that, it will probably be worth revisiting again.