A few decades after its release, it might be a bit easier to consider how terribly rare and valuable a film like Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Strains truly is. A musical about the rock industry directed with dollops of cynicism by Lou Adler, himself the founder of two record labels (and partially responsible for Monterey Pop), the film is a satire that keeps itself bottled tightly at all times into the confines of reality. There are countless other films that take swipes at the music business, from Phantom of the Paradise to Nashville to Josie and the Pussycats and even Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. The Fabulous Stains stays focused upon an emotionally accurate portrayal of its protagonist, the teenager Corinne Burns (a very young Diane Lane)–which firmly grounds the film’s somewhat bitter critique.

At the story’s outset, Corinne is already a minor celebrity in Charlestown, Pennsylvania, after being fired as a fry cook while the local news crew was shooting inside the restaurant. (To the cameras, she declares melodramatically, “This town died years ago!” Freeze frame on her scowl.) The opening credits play over an interview of Corinne conducted by the news station; we learn that her father was killed in the Army, and her mother has just died of lung cancer. She’s not going to school, but concentrating instead on her band, the Stains, whose other members include her sister Tracy (Marin Kanter) and cousin Jessica (Laura Dern).

We follow Corinne as she attends a concert headlined by The Metal Corpses, a washed-up, coke-addicted band that might have had a minor hit five or six years earlier. She–and the audience–are more infatuated by the opening punk rock act The Looters (think Sex Pistols without the success). The Looters–from England, and presumably a bigger deal there–are led by Billy (Ray Winstone), a frontman so cool that after his band’s performance, he stands in the wings to yell insults at the headliners. Corinne goes backstage and asks to audition for them, but, predictably, Billy ignores her.

Nevertheless, and for just this leg of the tour, they earn a position as an opening act for The Metal Corpses on the strength of their reputation as a known local band. Joining the tour bus, the Stains find themselves reaping equal parts loathing and condescension from both of the touring bands. And all signs indicate that the Stains have joined just as the tour is about to self-explode.

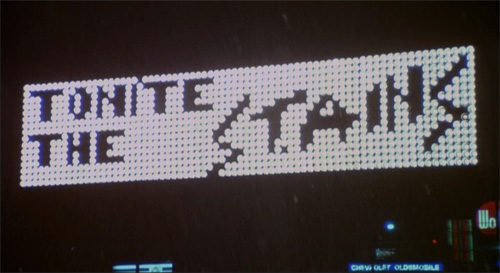

The Stains’ first performance on the road is utterly disastrous. The audience jeers Corinne’s performance, both of her bandmates subsequently abandon her onstage, and she strips down to her panties and slip and gives a slightly peculiar but genuinely enraged punk-rock-rant at a randomly-selected member of the audience. This might end the Stains’ presence on the tour, except for two distractions: backstage, one of The Metal Corpses dies of a drug overdose; and when the news crew follows up with Corinne to get her side of the story, she bullshits proudly that she was having an affair with the man. This salacious fiction, coupled with footage of Corinne’s onstage rant, make the Stains an overnight Pennsylvania success. With the Looters now leading the tour, the Stains opening, groupies begin to show up dressing as Corinne, spraying their hair with a white stripe like hers, and calling themselves “Skunks.” The Stains are becoming a phenomenon, and easily overtaking the Looters in popularity.

Billy can no longer ignore Corinne, nor does he want to. He sees potential in the Stains to be a quality punk band; but his awkward efforts to take Corinne under his wing are complicated by his growing attraction to her. Corinne, for her part, is wary of his intentions. Where The Fabulous Stains excels is in its identifying both characters as essentially naïve beneath their self-conscious punk-rock put-ons. For all his claims of experience (professionally and sexually), too frequently Billy looks and acts the lost child; and Corinne is in awe of fast-approaching stardom and all its trappings. She doesn’t resist the opportunity to merchandise the band, and soon their shows are hawking white hairspray and red transparent tee-shirts so every teenage girl can unload their allowance to look just like a Stain.

Corinne also begins imitating Billy’s moves onstage, and steals one of his songs. Ironically, her own music has an endearing simplicity and a Velvet Underground-style monotone that doesn’t seem out of place in a modern indie rock context. The Looters’ song, which she turns into a hit, becomes a more generic New Wave number, and also begins to lose its original punk intentions, subsumed under the gloss. Corinne can see this happening but seems both helpless and unwilling to prevent it. She witnesses the throngs gathering to imitate her, and can only be delighted. It’s finally Billy who mucks it up for her–as much out of simmering jealousy as his laboriously recited ethical qualms.

Parallels to Joan Jett and the Runaways are surely intentional, though Adler is more interested in the early days of an ephemeral rock sensation, when sudden fame is both euphoric and terrifying. Corinne is pressured into signing contracts before she understands what they mean–a cliché, but admirably understated here. Adler also hangs his story on the relationship between Corinne and Billy, how their conflicts both inform and threaten the development of the Stains, what it means to be punk and what it really means to be a sell-out. And whether being a sell-out is such a bad thing after all.

Adler lays it on the line that the Stains might be a shallow and disposable rock act. By the end of the film, their hit is only a cover song, and their emphasis on fashion statements has been absorbed into an MTV aesthetic, losing its original context as a statement of feminist independence. Yet he leaves the audience with a willingness to root for Corinne’s success; by this point, we’ve empathized with her too much to want to see her returned to a dead-end life. When she declares in an interview that “every girl should receive a guitar at the age of sixteen,” it’s simultaneously a canned sound bite and a sincere declaration. It’s finally left to the audience to draw that boundary between the authentic and the manufactured.