There are bad movies, there are movies that are so bad they’re good, and then there are movies that seem to have arrived from another dimension entirely, completely untranslatable to humankind. Such is the beautifully inexplicable Night Train to Terror.

If you go into this film knowing nothing about it (recommended), it takes a very long time to get acclimated to what you are actually seeing. And even then, each scene seems to arrive without any particular connection to the scene before it. There is a narrator who attempts to be helpful, but it quickly becomes apparent that his descriptions are clumsily trying to assemble the disparate images and scenes with masking tape and chewing gum, and the effort only adds to the disorientation. It’s an anthology film – that much is clear – whose framing device is a train occupied by Satan (as interpreted by a poor man’s Ricardo Montalban) and God (played by, according to the credits, Himself…talk about a casting coup). Out the window is the cosmos, so apparently they’re riding Galaxy Express 999. The only other passengers are…well, perhaps you’d better see for yourself, since words are genuinely inadequate here:

Okay, so there’s an 80’s rock video inside the train. But never mind, let’s switch moods and go immediately to our first story, told by Satan to God as a way of explaining how far Man has fallen. Over a scene of a couple losing control of their car – a car which looks like a Mini that’s been crushed into the width of a matchbox car – and plummeting off a bridge, we hear this E.C. comics-style narration:

This is the case of Harry Billings, a hard-working salesman during the day, at night a man who enjoys cars, women, and booze – sometimes a little too much. It is his wedding night, but his wife lies dead at the bottom of the river, and Harry lies in a sanitarium ward, about to enter a new life…of terror.

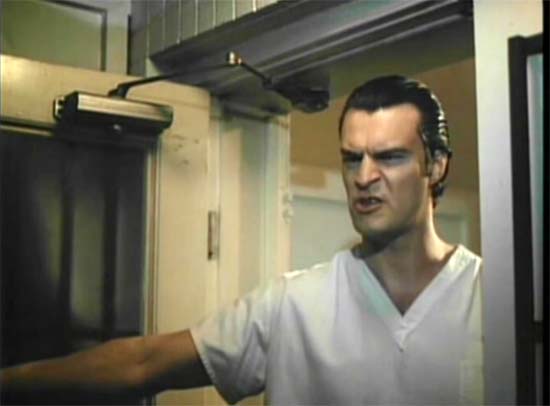

We see Harry Billings (John Philip Law of Barbarella and Danger: Diabolik), inside a padded cell, introduced to his warden, who is none other than Night Court‘s Richard Moll. His doctor and nurse are mad scientists, apparently, and within the space of a minute or so Billings is out doing their bidding, drugging women and delivering them back to the hospital, where they’re strapped nude to an operating table and cut into bloody pieces. We’re about five minutes into the film, and even the narrator is starting to sound a little winded explaining all of this. Incidentally, that whiplash sensation you’re experiencing will gradually lessen over the next 90 minutes; the film does not slow down one iota, but as you adjust to the pace, it will all begin to feel like a caffeine high as the film charges inexorably forward.

I suppose the more apt comparison would be that each of the film’s three segments plays like a trailer for a grindhouse film (or, oddly enough, even closer to the fake trailers in 2007’s Grindhouse, so over-the-top is the material). It’s evident that what you are seeing was not meant to play like this, and that you’re viewing, instead, a film that’s been edited down just past the point of coherency. According to the IMDB, the first segment is an unfinished film called Scream Your Head Off. It may have been unfinished, but they certainly got all the key scenes in: that is, as many naked women and general carnage as an entire motion picture could possibly contain, plus a humorous sequence in which John Philip Law spikes a woman’s communion cup without her noticing. The purpose of this evil hospital, we learn, is to provide organs to sell on the black market. But that’s not enough plot. We need more. So we’ve barely been introduced to the female mad scientist before she’s cheating on her husband (the other mad scientist person) with Law; and then, a few frames later, she’s drugging and lobotomizing her husband. Not to worry, the husband gets loose, and, with another shambling lobotomy-case, they perform the bloody operation on his wife. Satan declares victory in this segment, but God is unshaken. The film decides to take a breather, and we’re treated to some more sweatband-and-tights dancing, cinema’s ultimate palate cleanser.

But God and Satan are having a serious discussion here, people. The presence of the rock band, and its ungodly musicality, understandably leads Satan to the hypothesis that all musicians hate God. And so we are treated to my favorite exchange in the film:

Satan: “I’ve never heard one of them pray.”

God: “That’s because you don’t listen to their music.”

Satan: “You call that music, what they’re playing?”

God: “Some of it is quite touching.”

Satan: “It never touches me.”

God: “You have no tears. You don’t know how to cry.”

Satan: “Well, I can laugh. Ha, ha! That’s better than tears.”

God: “I can laugh and cry at the same time.”

This mind-boggling metaphysical debate encapsulates the style of Night Train to Terror, with each statement outclassed, and out-WTF’d, by the one which follows. And so the train rockets forward into further uncharted territory, which other genre films would not dare approach…

This is a strange love story, the case of Gretta Connors, a young musician from a small town. To support her piano playing, she worked in a carnival. She came to the big city to find success and love. Instead, she found George Youngmeyer. And as so often happens to the young, they are so desperate, they’ll believe anything or anyone. Gretta gave herself completely to Youngmeyer. He promised to make her famous, but used Gretta for his own purposes. She wanted to be a movie star, so – he made her a star. This is Glenn Marshall, college graduate, enrolled in medical school. He stopped by his fraternity house for a beer one day…a day that would change his life. He saw Gretta in one of Youngmeyer’s movies. It was love at first sight. Glenn had to find her. Glenn’s obsession finally brought him to George Youngmeyer’s Manhattan club where Gretta was playing…

As this narration is read, we’re treated to a collage of scenes which must represent at least half an hour of the original source material (a 1983 film called Carnival of Fools). We see Gretta selling popcorn at a carnival, the popcorn display strapped around her neck as though she were a cigarette girl in a 1930’s jazz club. She meets Youngmeyer, who shoves dollar bills down her blouse until she decides to come with him (he tosses the popcorn aside with a lustful grin). While the narrator describes how much Gretta loves the piano, we only see Youngmeyer playing, while she sits beside him and lasciviously devours an ice cream cone. “He made her a star!” the narrator proclaims, and so we see Gretta writhing nude in a porno, in this film’s idea of ironic understatement. And Glenn is watching the porno at the frat party, so naturally: “It was love at first sight!”

With this set-up, we expect to see a tale of revenge, with Glenn trying to win Gretta away from Youngmeyer, and the old man destroying the young couple, and destroying himself in the process, et cetera, et cetera. It’s a little less easy to predict that the three will rapidly join a “Death Club,” a strange little cult of wealthy nihilists, taking thrills out of overly-elaborate variations on Russian Roulette. First they sit around a table, a jar containing a giant stop-motion wasp in the center. When they release the wasp, they all remain perfectly still to see which victim it claims (its sting will kill both the wasp and its prey). But the window is left open, for the same reason, we’re told, that a gun in Russian Roulette must have one empty chamber. (Actually, I thought the game involved all empty chambers except for one bullet, but never mind.) The wasp flies about the room, looking like something Ray Harryhausen might have created at the age of four or five. After teasing everyone by landing on their shoulders or their hands, it zips out the window, and the cultists, drenched in sweat, grin at each other, euphoric from their brush with death. Then the wasp attacks an innocent couple walking by outside, killing one of them. C’est la vie.

The death games continue: they wire themselves to a giant computer which will randomly select one of them for death (or not; “empty chamber” and all that). One of their members is violently electrocuted. Finally, they all lie in sleeping bags while a giant wrecking ball sweeps in a circle over their heads. When it’s released, it will crush one of them (or not…”empty chamber”). The mechanism is described in great detail by Youngmeyer, with excited interjections from a death club member who sounds like he’s been dubbed by Mike Meyers in one of his less successful SNL characterizations. With the cultists in place, the ball swings, is released, and SPLAT! goes the head of the contessa who is not actually relevant to the plot of this story. Cut to God, back in the train, looking either disgusted or confused, or both.

Obviously it’s time for another exciting dance number. But the band has been dancing and playing that song for so long that they’re slowly starving to death. “How about some hamburgers and beer?” Sorry, friend: as the conductor will tell you, there’s no food on this train. Only colored spotlights and smoke machines.

The case of Claire Hansen: a highly respected surgeon, a devout Catholic, and wife to Nobel prize winner James Hansen. It is midnight, time of dark dreams…and Claire Hansen is about to begin a living nightmare.

The final (and longest) segment is crudely edited down from a film called Cataclysm (1980), and judging from the material shown here, it easily outdoes Omen III: The Final Conflict for unhinged Apocalyptic madness. I kind of love it. There’s a large cast of characters, scrambling for the editor’s attention. Richard Moll (again) plays the author James Hansen, who has just written a book called, subtly, God is Dead. He gets his own television special, in which he sits at a table with a glass of water and a white lacy tablecloth, and declares, “What I have to say to you tonight may cause you pain. It may disillusion you. It may even make you hate me.” Then he proclaims that Jesus is a myth and never actually existed. We don’t see much more of this special, but presumably it’s about half an hour more of this. Veteran character actor Cameron Mitchell plays Lieutenant Sterne, overacting wildly as he tries to convince an old Jewish gentleman that handsome socialite Olivier is not really the immortal incarnation of the Devil. At a party so debauched that it has a belly dancer with a python, Olivier sits observing from a throne, beautiful women to either side of him, until he selects a girl from the crowd who will pleasure him for the evening. She goes home with him, where he seductively begins to remove his shoes, revealing cloven feet.

Meanwhile, James Hansen, a man so brazenly atheist that he won the Nobel prize, is approached first by a shaggy-looking monk-like fellow, who declares that the Devil walks among us. The stranger is laughed away. Then Hansen is approached by the Devil, who seems to confuse atheism with Satanism. No, Hansen has to answer with great exasperation: I don’t believe in the Devil either. To which he’s immediately attacked by a stop-motion demon, transformed into a Gumby-like character himself, and thrown into an abyss. Did I mention there’s a lot of stop motion in Night Train to Terror? Unfortunately, it manages to look like this:

More stuff happens. The monk-like fellow meets a succubus-like woman in a tower, and then he, too, is destroyed by the evil powers of Claymation. Lieutenant Sterne attends bodies in the morgue with 666 scrawled on the tops of their heads (Damien-style), and threatens Mr. Olivier with stock phrases like “I’ve got lots of time. Time is all I have. And I’m going to spend an awful lot of it checking on you.” But Olivier outwits Sterne, and even murders his aged fellow officer in what must be the biggest car explosion of all time:

So yes, the Devil can make a car blow up like the Bridge on the River Kwai.

The climax seems to combine the bloody hospital madness of Segment 1 with the diabolical body-swapping conclusion of The Exorcist. Suffice it to say, evil wins. You would think that when we return to our indelible framing device, God would be demoralized, having witnessed Satan triumph in tale after poorly-edited tale. But God seems delighted, and the rockers next door breakdance on, as the train collides with destiny:

So listen. If you don’t have the chance to witness Night Train to Terror in a beautiful print on the big screen (and let’s face it, you probably won’t, unless you were one of the lucky members in attendance at the 2011 Wisconsin Film Festival), do all in your power to track down a copy so you can experience the full 90 minutes in all of its choppy, incoherent glory. Exploitation filmmaking has never been so accidentally masterful.