For almost three straight decades, Hammer Studios garnered a wide following for their horror pictures. Famously, these movies were, on the whole, literate, well-acted, colorful, sexy, and just bloody enough. At the forefront of Hammer’s brand, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee rapidly became marquee names, and they fronted the studio’s two key franchises: one for Dracula, one for Frankenstein. Both series traced the same trajectory. In the late 50’s and early 60’s, these pictures were at their zenith, usually directed by Terence Fisher (who brought an elegant kineticism), and with scripts (frequently by Jimmy Sangster or Anthony Hinds) that paid homage to the original novels while compressing their most famous elements into efficient 90-minute tales. But by the early 70’s, a sense of creative exhaustion touched the Dracula and Frankenstein pictures both, and as newer, edgier horror films began to dominate the market, the Hammer Horrors saw their budgets slashed and their profits decline; the end came slowly but inevitably. Still, for a while, “monster kids” on both sides of the ocean had it very, very good, and to this day Hammer has such a cult following, and is still such a recognizable name, that it was resurrected for a new string of horror films (beginning with the superb Let Me In last year). Revisiting the classic Hammer run, it’s fascinating to see that their two tentpole series could sustain this many installments. Dr. Frankenstein and the Count competed with James Bond nearly every year for the attention of genre fans. In film after film, Lee’s Dracula would rise from the grave, only to be staked back down again; Cushing’s cunning doctor would find a new laboratory, a new assistant, and commit more blasphemies in the name of science. Each series had its lows: in my opinion, Dracula had more than Frankenstein, perhaps because the Count’s scripts required less inspiration. But both series also reached a point where, on the verge of becoming numbingly repetitive, a script arrived to upend the usual cliches and provide an adventure very different for its singular characters. In the Dracula line, that was Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), the last really good entry in that series, but also atypical and thematically intriguing. For all the same reasons, I’m fascinated by Frankenstein Created Woman (1967).

The title character barely figures into Taste the Blood of Dracula, and, although the good doctor gets some delicious lines and moments, Frankenstein is also a bit sidelined in Created Woman. Instead, for nearly half the film’s running time, we’re following the tale of Hans and Christina, two young lovers fated for a tragic end. Hans (Robert Morris) is one of Frankenstein’s two assistants (the other is Dr. Hertz, played with an endearing daffiness by Thorley Walters); and Christina (Susan Denberg) is the daughter of the local tavernkeeper. Half of her face is disfigured, so – in an unusually sensitive and observant touch for a Hammer programmer – she lets her long hair fall over that side, as she shyly keeps to the kitchen. When three entitled village bullies cruelly insult the girl, Hans flies into a rage, attacking them. Later that evening, the three men return to the pub to steal some liquor. Christina’s father discovers them, and they retaliate by beating him to death. The passionate and violent Hans is assumed to be the culprit, for he has no alibi – he was spending the evening in bed with Christina, and refuses to admit it, even though doing so would save his life. (I noticed a Hammer fan posted his disbelief of this plot point on a message board, but it’s important to remember that the film is set in the 19th century, not the 20th. Hans is trying to uphold Christina’s name, an extension of how fiercely protective he has become of her.) Although Dr. Frankenstein testifies on behalf of the boy’s good character, Hans is convicted of murder, and sentenced to the guillotine…the same fate suffered by his father years before. Indeed, this theme of grim, inescapable fate will become more prominent as the story progresses.

Distraught, and wracked with guilt, Christina drowns herself in a river. We’re about halfway through the film, and both of our protagonists are dead. The narrative refocuses itself upon Victor Frankenstein, first by highlighting his unusual reaction upon learning the news: not grief, but an eager enthusiasm for the opportunity to put his latest experiments to their ultimate test. And this is what really puts the Frankensteins a notch above the Dracula pictures: by having the doctor, and not the monster, be the recurring character in the series, the stories become more dynamic and inventive, and tend to focus on moral dilemmas rather than conflicts of good vs. evil. Frankenstein is not a monster, though he can be. He’s amoral, placing science and the spirit of discovery above the lives of everyone around him. There’s a delightful scene in Frankenstein Created Woman when he’s called into the courtroom, and pages through the witness stand Bible with mild disinterest, before impatiently reporting his praise of Hans, and the stupidity of everyone else in the courtroom, as though nothing were more obvious, and how irritating it is to have to be asked. We’ve been stuck with the inexorably unfolding tragedy of Hans and Catherine for so long that this triumphant return of our (anti)hero might have you cheering. But, of course, he’s not terribly put out by Hans’ subsequent execution either, since the body’s left unguarded. When life gives you lemons, and all that.

Despite his diminished presence, Frankenstein is still the star of the show. We witness the casual way he dominates – albeit tenderly – the scatterbrained Dr. Hertz, a man who was once a capable physician, but whose faculties have retreated with age, leaving him to trust Victor’s brilliance unquestioningly. In one scene, Frankenstein actually coaches Hertz on how to properly blackmail someone, and Hertz obediently lets wickedness blossom. Admittedly, Frankenstein’s latest experiments are a wee bit convoluted, not to mention absurd. First he goes to great lengths to prove a man’s soul survives death for a certain interval (the doctor is introduced being unthawed from lethally low temperatures, and then has his soul safely restored to his body). Next, he creates a sort of invisible and impenetrable force field which can stop a bullet. Never mind potential military applications; such thoughts wouldn’t occur to the doctor. He wants to use this force field to trap the soul of a dead man for an indefinite period until it can be transplanted into a new body. And this is exactly what he’ll do with Hans and Christina, the dead young lovers. He will restore them to life by joining them: placing Hans’ preserved soul in Christina’s body, reanimating her.

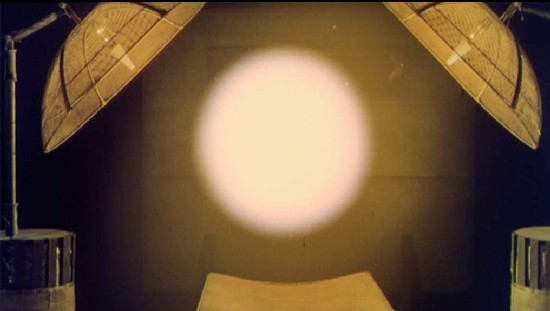

What exactly a “soul” is, by the film’s definition, is a bit unclear. Well, let me restate that. We can see precisely what a soul is, courtesy special effects: it’s a bright glowing sphere of light. (Martin Scorsese has called this moment of the film “sublime,” making it one of his favorite Hammer horrors.) The question the film asks is: of what import is a soul? In any other Frankenstein film, he’s handling more tangible grue. Consider how much simpler it would have been if he merely placed Hans’ brain in Christina’s body. Yet by having his doctor conduct the world’s first soul transplant, screenwriter Anthony Hinds (as “John Elder”) nudges this, the fourth film of the series, from the realm of science fiction into the metaphysical (if not theological). A brain transplant would be so very uninteresting, straightforward and, as far as the mad scientist subgenre goes, commonplace. What happens to Christina would lose all its mystery and much of its peculiar impact.

Because Christina undergoes a most unexpected transformation. We expect Dr. Frankenstein to create hideous monsters. In a complete reversal of the cliche, the doctor makes the resurrected Christina beautiful, curing her of deformity. (And, humorously, he also makes her a blonde. Cushing covers for this with a throwaway line implying it’s a predicted side effect.) At first it’s uncertain just what the new Christina will be: will her personality be hers, or Hans’? What about her memories? Or is the “soul” something less easily definable? Soon enough, and rather late into the film, the murders begin. One by one, she seduces and then slaughters the three boys who killed her father and ushered Hans to the guillotine. This, the most traditionally “horror” element of the entire film, occurs only in the last half hour or so. What did audiences think of a horror film that so withheld its exploitation elements? Regardless, it’s not the killings, but the transgendered-fantastique twist that gives these scenes their charge. Is it Hans who is seducing the men (homoerotically), or Christina (who might have been raped by them if Hans hadn’t intervened)? Or is it a third personality with elements of both lovers, but more base, more primal – more hateful – let loose by the doctor’s experiment? In one of the film’s most electric images, and its most authentically horror, we see that Christina actually keeps Hans’ severed head – carries it around in a hatbox – and converses with it before committing the murders.

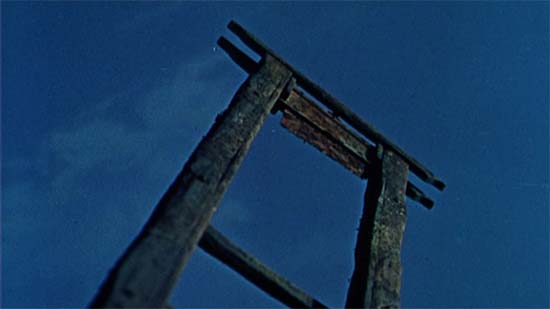

The doctor does catch up with Christina, after she has claimed all her intended victims. But she runs from him, and willfully plunges again into the river, to commit suicide a second time. This circular or echoing resonance is horrifying, largely because it’s been so foreshadowed that we’ve subliminally dreaded it. It’s like the recurring image of the guillotine, first with the film’s prologue, in which Hans, as a child, witnesses his father’s execution (after he implores his son to leave and hide his eyes), and then with Hans’ own demise, when he also implores Christina – another accidental witness – to turn away from him before the blade drops. We know history will repeat itself with Christina, and that Frankenstein never should have brought her back to life…but it’s wrenching to see her drop into the water.

Hammer films always end abruptly, and Frankenstein Created Woman is no exception. Peter Cushing looks down at the water desperately, and then resignation sweeps quickly over his face. It’s left to the viewer to wonder if he regrets Christina’s death, or merely that another experiment has come to an end. He turns his back and the credits roll.

Hammer tried to sell the film on its sexy starlet, and publicity stills were taken of Cushing carrying a bikini-clad Denberg about the lab. Like so many stills of the day, the pictures lied. Even when Christina begins to seduce, she’s pretty damn clothed. Director Fisher was absolutely right to focus on the Shakespearean qualities of the tale, without accentuating exploitation (despite the title – which was written before the story was – that spoofs Roger Vadim’s famous film). This is one of the most subtle and poetic entries in Hammer’s catalog, building upon themes introduced in 1958’s Revenge of Frankenstein (the second of the series, in which the doctor tries to transplant the brain of his deformed assistant into a muscleman, with similarly tragic results). It’s a richly satisfying work, and stands taller on multiple viewings. Another fascinating sequel followed – Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed – but that’s a grisly tale for another day.