Monty Python animator Terry Gilliam finally came into his own with 1981’s Time Bandits, a film which put him on the map as a cinematic fantasist to be reckoned with. But it took a few attempts. Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), which he co-directed with Terry Jones, was crudely made but looked great, and soared on the basis of the script and performances; Jabberwocky (1977), his first solo feature, was an interesting but uneven experiment to make a darker medieval satire, but if it’s considered a failure, it’s a failure that looked even more great. His filmmaking skills were developing, gradually, into the ability to translate his psychedelic Python cartoons into live action widescreen grandeur. And his third film hit the sweet spot.

Monty Python animator Terry Gilliam finally came into his own with 1981’s Time Bandits, a film which put him on the map as a cinematic fantasist to be reckoned with. But it took a few attempts. Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), which he co-directed with Terry Jones, was crudely made but looked great, and soared on the basis of the script and performances; Jabberwocky (1977), his first solo feature, was an interesting but uneven experiment to make a darker medieval satire, but if it’s considered a failure, it’s a failure that looked even more great. His filmmaking skills were developing, gradually, into the ability to translate his psychedelic Python cartoons into live action widescreen grandeur. And his third film hit the sweet spot.

It’s a children’s movie, ostensibly, co-written with fellow Python Michael Palin and featuring cameos by celebrities large and small. But the starring role, and the crucial point of view, lies with newcomer Craig Warnock, playing Kevin, a child with a vast imagination that one day literally blows out the walls of his confining bedroom. There’s plenty of evidence that the two hours of adventure which follow take place entirely in his own head, from the fact that the drawings and toys cluttering his bedroom are subsequently brought to life in the time-and-dimension spanning vignettes, to the child’s-logic plotting…even the theme song, by producer George Harrison, is entitled “Dream Away.” But it’s a bit of a moot point. We are within young Kevin’s head, and it’s fruitless to try to distinguish what is real and what is not; we’re experiencing both his wonder and his fear, barreling forward through the fantastic worlds like passengers on a theme park ride. It shouldn’t be too big a surprise that the film won over audiences, but has there ever been a darker, more bizarre box office hit? (Gilliam wouldn’t get that lucky with paying customers again until 1991’s The Fisher King.)

It’s a children’s movie, ostensibly, co-written with fellow Python Michael Palin and featuring cameos by celebrities large and small. But the starring role, and the crucial point of view, lies with newcomer Craig Warnock, playing Kevin, a child with a vast imagination that one day literally blows out the walls of his confining bedroom. There’s plenty of evidence that the two hours of adventure which follow take place entirely in his own head, from the fact that the drawings and toys cluttering his bedroom are subsequently brought to life in the time-and-dimension spanning vignettes, to the child’s-logic plotting…even the theme song, by producer George Harrison, is entitled “Dream Away.” But it’s a bit of a moot point. We are within young Kevin’s head, and it’s fruitless to try to distinguish what is real and what is not; we’re experiencing both his wonder and his fear, barreling forward through the fantastic worlds like passengers on a theme park ride. It shouldn’t be too big a surprise that the film won over audiences, but has there ever been a darker, more bizarre box office hit? (Gilliam wouldn’t get that lucky with paying customers again until 1991’s The Fisher King.)

Kevin has been abducted out of his room by the Time Bandits; or, more precisely, he flees with them as none other than the Supreme Being (a giant animated Oz-like head, cloaked in mist and light) invades from behind his bed, and the Bandits are forced to push at one of the bedroom walls until it slides forward, and forward, and forward, revealing a long dark corridor. (“It’s never done that before,” Kevin admits.) Then they fall into a pit, escaping down a hole in space and time, which drops them into 1796 Italy and the Battle of Castiglione. The Time Bandits are six dwarves who once served the Supreme Being, and were responsible for creating all the Earth’s trees. They were demoted, as Bandit leader Randall (David Rappaport) explains, because they made the Pink Bunkadoo. “Lovely tree…six hundred feet high, bright red, and smelled terrible.” Sent to the Repairs Department to fix the fabric of the universe, they instead elected to steal the map of all the holes, so they could dip in and out of history to become “stinking rich.” So Kevin becomes their unwitting accomplice as they rob Napoleon (Ian Holm), and then escape through one of the time holes into Medieval England, long before Napoleon is born. But unbeknownst to the Time Bandits, Evil (David Warner) is making plans to steal the map for his own nefarious ends.

Kevin has been abducted out of his room by the Time Bandits; or, more precisely, he flees with them as none other than the Supreme Being (a giant animated Oz-like head, cloaked in mist and light) invades from behind his bed, and the Bandits are forced to push at one of the bedroom walls until it slides forward, and forward, and forward, revealing a long dark corridor. (“It’s never done that before,” Kevin admits.) Then they fall into a pit, escaping down a hole in space and time, which drops them into 1796 Italy and the Battle of Castiglione. The Time Bandits are six dwarves who once served the Supreme Being, and were responsible for creating all the Earth’s trees. They were demoted, as Bandit leader Randall (David Rappaport) explains, because they made the Pink Bunkadoo. “Lovely tree…six hundred feet high, bright red, and smelled terrible.” Sent to the Repairs Department to fix the fabric of the universe, they instead elected to steal the map of all the holes, so they could dip in and out of history to become “stinking rich.” So Kevin becomes their unwitting accomplice as they rob Napoleon (Ian Holm), and then escape through one of the time holes into Medieval England, long before Napoleon is born. But unbeknownst to the Time Bandits, Evil (David Warner) is making plans to steal the map for his own nefarious ends.

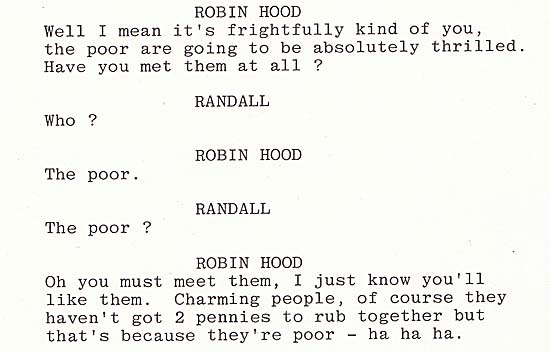

The premise provides a vast, convenient playground for screenwriters Gilliam and Palin. It allows them to indulge in Pythonesque sketches (such as John Cleese playing a Prince Charles-like Robin Hood), satirize religion and philosophy, and serve up some eye-popping fantasy setpieces, particularly when they reach the Time of Legends and Evil’s towering black castle, which foreshadows Peter Jackson’s take on Tolkien’s Orthanc…though Gilliam’s seems taller. If nothing else, Time Bandits succeeds as a classic fantasy film simply by providing one indelible image after another, from the knight and horse which launches straight over Kevin’s bed at the film’s outset, to a desert duel between Agamemnon (Sean Connery) and a club-wielding minotaur, to the galleon that rides the bald head of a giant. This last sequence most successfully recreates Gilliam’s animation in its pure stream-of-consciousness trippiness: our heroes are fished out of the ocean by a giant ogre (Peter Vaughan), and after they steal his ship and dump him and his wife (Katherine Helmond) into the water, he coughs some wind into the sails, blowing the ship onward…before it’s revealed that the ship is actually riding a giant, who rises out of the water and stomps onto the land, crushing some trolls in the midst of a domestic dispute. So what’s the sense of having the ogre seem to propel the ship forward, since it’s actually stuck on the head of a giant? It doesn’t matter. We’re in Gilliam’s (or Kevin’s) imagination, and the logic only works forward, not backward.

The premise provides a vast, convenient playground for screenwriters Gilliam and Palin. It allows them to indulge in Pythonesque sketches (such as John Cleese playing a Prince Charles-like Robin Hood), satirize religion and philosophy, and serve up some eye-popping fantasy setpieces, particularly when they reach the Time of Legends and Evil’s towering black castle, which foreshadows Peter Jackson’s take on Tolkien’s Orthanc…though Gilliam’s seems taller. If nothing else, Time Bandits succeeds as a classic fantasy film simply by providing one indelible image after another, from the knight and horse which launches straight over Kevin’s bed at the film’s outset, to a desert duel between Agamemnon (Sean Connery) and a club-wielding minotaur, to the galleon that rides the bald head of a giant. This last sequence most successfully recreates Gilliam’s animation in its pure stream-of-consciousness trippiness: our heroes are fished out of the ocean by a giant ogre (Peter Vaughan), and after they steal his ship and dump him and his wife (Katherine Helmond) into the water, he coughs some wind into the sails, blowing the ship onward…before it’s revealed that the ship is actually riding a giant, who rises out of the water and stomps onto the land, crushing some trolls in the midst of a domestic dispute. So what’s the sense of having the ogre seem to propel the ship forward, since it’s actually stuck on the head of a giant? It doesn’t matter. We’re in Gilliam’s (or Kevin’s) imagination, and the logic only works forward, not backward.

It’s often been said that Gilliam’s weakness is dealing with actors, a lie frequented as often as the notion that all his films go over-budget. The idea goes like this: any director who pays particular attention to visuals must be giving short-shrift to the performances. It’s true that after Holy Grail Gilliam decided against directing further Monty Python films, since he had such difficulty directing his teammates. But it’s pretty evident in the entirety of his filmography that he adores his casts, and if you’re not too distracted by the superb effects work then you might care to notice that he’s given fantastic character actors some of their signature, showcase roles: think Jonathan Pryce, Ian Holm, Michael Palin, and Katherine Helmond in Brazil (1985), Pryce, John Neville, Oliver Reed, and Eric Idle in Munchausen (1988), Jeff Bridges and Robin Williams in The Fisher King (1991), or Johnny Depp and Benicio del Toro in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998). In Time Bandits, one of the chief joys in the structure is being able to move from one tour-de-force performance to the next. Holm, for example, as a height-sensitive, Punch-and-Judy-loving Napoleon Bonaparte (“That’s what I like – little things, hitting each other!”). Or Connery as benevolent warrior-king Agamemnon, providing the parental surrogate Kevin sorely needs, but can’t keep. But best of all: Rappaport as the would-be criminal mastermind Randall, at one point accidentally flicking cigar ashes on Kevin’s head and then casually dusting them off; Warner as the scenery-chewing Evil, offering one venomous line after another (“[The Supreme Being] created slugs! They can’t speak, they can’t hear, they can’t operate machinery. I mean, are we not in the hands of a lunatic?”); and the late surprise cameo by Sir John Gielgud as God, an efficient, reasonably fair-minded CEO. God saves the day, as it happens, but he’s a deliberately disappointing incarnation, wearing a white business suit and not particularly caring too much about what happens to Kevin. That’s Gilliam’s worldview: the world is just a flat backdrop, and behind it are just ordinary men working pulleys and rope.

It’s often been said that Gilliam’s weakness is dealing with actors, a lie frequented as often as the notion that all his films go over-budget. The idea goes like this: any director who pays particular attention to visuals must be giving short-shrift to the performances. It’s true that after Holy Grail Gilliam decided against directing further Monty Python films, since he had such difficulty directing his teammates. But it’s pretty evident in the entirety of his filmography that he adores his casts, and if you’re not too distracted by the superb effects work then you might care to notice that he’s given fantastic character actors some of their signature, showcase roles: think Jonathan Pryce, Ian Holm, Michael Palin, and Katherine Helmond in Brazil (1985), Pryce, John Neville, Oliver Reed, and Eric Idle in Munchausen (1988), Jeff Bridges and Robin Williams in The Fisher King (1991), or Johnny Depp and Benicio del Toro in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998). In Time Bandits, one of the chief joys in the structure is being able to move from one tour-de-force performance to the next. Holm, for example, as a height-sensitive, Punch-and-Judy-loving Napoleon Bonaparte (“That’s what I like – little things, hitting each other!”). Or Connery as benevolent warrior-king Agamemnon, providing the parental surrogate Kevin sorely needs, but can’t keep. But best of all: Rappaport as the would-be criminal mastermind Randall, at one point accidentally flicking cigar ashes on Kevin’s head and then casually dusting them off; Warner as the scenery-chewing Evil, offering one venomous line after another (“[The Supreme Being] created slugs! They can’t speak, they can’t hear, they can’t operate machinery. I mean, are we not in the hands of a lunatic?”); and the late surprise cameo by Sir John Gielgud as God, an efficient, reasonably fair-minded CEO. God saves the day, as it happens, but he’s a deliberately disappointing incarnation, wearing a white business suit and not particularly caring too much about what happens to Kevin. That’s Gilliam’s worldview: the world is just a flat backdrop, and behind it are just ordinary men working pulleys and rope.

But is it for children? I shouldn’t spoil the ending, but it’s…memorable. Controversial, perhaps, but so gleefully unexpected, random, and pitch-dark that it manages to evoke the unsanitized versions of the Grimm fairy tales. (More successfully, to be sure, than his later, compromised film The Brothers Grimm.) Yet it’s not traumatic or even all that disturbing. It’s palatable and mysteriously satisfying. In an interview on the Image BluRay disc, Gilliam explains how he got away with it: due to sound problems at a test screening, audiences were so eager for the experience to be over that they claimed on the comment cards that “the ending” was their favorite part. This was interpreted without irony by the studio. One doubts that the finale will remain intact in the supposedly-upcoming remake; this original work will remain unique. Time Bandits is just a little dangerous, just a little adult, portraying a world full of possibilities but bordered by darkness. So, yes, it’s perfect for kids, because it reflects how they already see the world around them.

But is it for children? I shouldn’t spoil the ending, but it’s…memorable. Controversial, perhaps, but so gleefully unexpected, random, and pitch-dark that it manages to evoke the unsanitized versions of the Grimm fairy tales. (More successfully, to be sure, than his later, compromised film The Brothers Grimm.) Yet it’s not traumatic or even all that disturbing. It’s palatable and mysteriously satisfying. In an interview on the Image BluRay disc, Gilliam explains how he got away with it: due to sound problems at a test screening, audiences were so eager for the experience to be over that they claimed on the comment cards that “the ending” was their favorite part. This was interpreted without irony by the studio. One doubts that the finale will remain intact in the supposedly-upcoming remake; this original work will remain unique. Time Bandits is just a little dangerous, just a little adult, portraying a world full of possibilities but bordered by darkness. So, yes, it’s perfect for kids, because it reflects how they already see the world around them.

Unsurprisingly, given Gilliam’s notorious luck, the remake is moving forward while his own follow-up script, written a decade ago or more, gathers dust. But Time Bandits is actually the first of an informal series of films, already completed: the so-called Dreamer Trilogy. Gilliam has said in interviews that it continues with the dreamer in middle age (Brazil, in which Sam Lowry is like a grown-up Kevin), and in the twilight years (Baron Munchausen, which equally confuses dreams with reality). So those are the sequels and the remakes: let’s keep it that way. Time Bandits is best left alone, a relic of a time in the early 1980’s when such a film might slip through the cracks, or the holes left unrepaired. Appropriately released by “Handmade” Films, it’s unadorned by CG, IMAX 3-D, or intangible greenscreen environments. It’s gritty, sometimes awkwardly paced, black-humored, philosophical, cosmic, and messy. It’s the stuff of life, the universe, and everything; even the Pink Bunkadoo.

Unsurprisingly, given Gilliam’s notorious luck, the remake is moving forward while his own follow-up script, written a decade ago or more, gathers dust. But Time Bandits is actually the first of an informal series of films, already completed: the so-called Dreamer Trilogy. Gilliam has said in interviews that it continues with the dreamer in middle age (Brazil, in which Sam Lowry is like a grown-up Kevin), and in the twilight years (Baron Munchausen, which equally confuses dreams with reality). So those are the sequels and the remakes: let’s keep it that way. Time Bandits is best left alone, a relic of a time in the early 1980’s when such a film might slip through the cracks, or the holes left unrepaired. Appropriately released by “Handmade” Films, it’s unadorned by CG, IMAX 3-D, or intangible greenscreen environments. It’s gritty, sometimes awkwardly paced, black-humored, philosophical, cosmic, and messy. It’s the stuff of life, the universe, and everything; even the Pink Bunkadoo.