This is my favorite of the Val Lewton-produced films, a very curious mixture of horror and film noir that fans of either genre should embrace with equal zeal. Mark Robson was not as naturally gifted a director as Jacques Tourneur, and he even steals from Tourneur’s Cat People (1942) for a scene late in this film (a Lewton trademark: a girl walking alone down a shadowy street)–but even Tourneur stole from Cat People, and it cannot be denied that The Seventh Victim is so strange that ultimately it’s a complete original. In fact, it’s a wonder that the film ever got made.

This is my favorite of the Val Lewton-produced films, a very curious mixture of horror and film noir that fans of either genre should embrace with equal zeal. Mark Robson was not as naturally gifted a director as Jacques Tourneur, and he even steals from Tourneur’s Cat People (1942) for a scene late in this film (a Lewton trademark: a girl walking alone down a shadowy street)–but even Tourneur stole from Cat People, and it cannot be denied that The Seventh Victim is so strange that ultimately it’s a complete original. In fact, it’s a wonder that the film ever got made.

The plot, on the face of it, is a very simple mystery. Mary (Kim Hunter of A Matter of Life and Death) ventures forth from the Catholic school she attends to find her older, sophisticated and worldly sister Jacqueline (Jean Brooks, with a Bettie Page haircut and a sultry pout). Jacqueline’s gone missing, but it seems that everyone is after her, including her husband Gregory Ward (Leave it to Beaver’s Ward Cleaver, Hugh Beaumont) and some menacing types who urge a detective hired by Mary to mind his own business. More characters than are absolutely necessary are added to the mix: Dr. Judd (Lewton mainstay Tom Conway), who claims to be Jacqueline’s new lover; Jason Hoag (Erford Gage), a poet and acquaintance of Judd’s who tries to help Mary out; the proprietors of a cafe called, significantly, The Dante; the terse Miss Redi (Mary Newton), owner of a perfume business of which Jacqueline was once co-owner; and a mysterious, exclusive society to which Jacqueline belongs. It is revealed, after a fairly long wait, that this society worships the Devil. Jacqueline betrayed their trust, and now they want her to die.

On certain matters–those not related to a major theme which I’ll get to in a moment–the film feels just slightly undercooked, and one suspects that either significant scenes of exposition were cut, or the script was rushed too hurriedly into production. The presence of many male characters suggests an attempt to develop a love triangle a la Cat People or I Walked with a Zombie (1943); but little time is spent developing the relationships, and more often we’re told who is in love with whom rather than feeling it. And why does Dr. Judd know telepathy (used in only one scene)? And who is that mysterious woman next door who claims to be dying? And isn’t it odd that the secret society claims to worship the Devil, yet we see them do nothing of the sort? (I assume the Hays Code has something to do with that last point.) It might take multiple viewings to see how seemingly random elements connect. For example, late in the film Dr. Judd tells Jason, “That girl you loved, that other patient of mine. She didn’t disappear. She’s in an asylum, a horrible, raving thing.” It’s very easy to forget that much, much earlier in the film, a brief exchange between these two revealed that this was their connection: Jason loved one of his patients. That this character arc should be introduced and concluded in two curt dialogue scenes strikes me as bizarre. They could just as easily have been discarded altogether, except that Dr. Judd’s last words on the subject are so callous and so invaluably haunting.

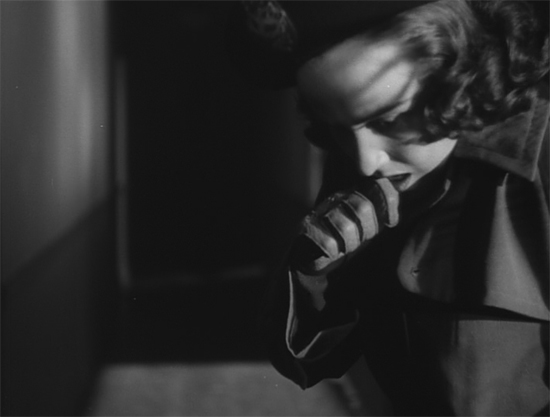

All of Lewton’s films seem to toss their characters into a whirlpool. They’re swimming around an abyss that’s about to swallow them, and it’s this existential despair, so unfaked, that sets his string of horror films apart from your Universals and your Hammers and your giallos. The Seventh Victim has its weaknesses, including the strangely underdeveloped script, but those weaknesses are also its strengths. The random, isolated scenes become like moments in a fever dream. Subsequently, The Seventh Victim, of all the Lewtons, feels the most unhinged. It’s “a horrible, raving thing.” That Mary leaves a holy place to find her sister, and almost immediately heads for a cafe called The Dante, explicitly outlines that she is on a journey into the Inferno. (In the cafe she finds the poet Jason lurking below a painting of another poet, Dante Alighieri–right under his feet.) The proprietors of The Dante rented a room to Jacqueline, Room Number Seven, and it’s here that Mary sees the most horrifying image in the film: there is nothing in the room but a stool and a noose hanging above it. Later, Gregory Ward explains that Jacqueline rented the room without the intention of using it. She wanted to know that she could die, that it was an option she was not choosing. He seems to find it harmless. But a glance at Dante’s Inferno reveals that those who commit suicide, a mortal sin, are destined for the Seventh Circle, where they are transformed into thorny trees and torn at by Harpies. Here, then, is The Seventh Victim’s true subject: suicide. Jacqueline, hounded by the devil-worshippers, feels that she has nowhere to run. In her panic, she kills the detective hired by Mary when he discovers her hiding place. This is one of the film’s most memorable scenes, as Mary and the detective gaze down a pitch-black hallway, the Abyss Itself. Mary cannot bring herself to walk down it, even if her sister is lurking at the other end, so she urges the detective to go alone. He emerges from the darkness a moment later, staggering, before collapsing dead.

Significantly, the film opens and closes with a quote by John Donne, first glimpsed written upon a stained-glass window: “I run to death, and death meets me as fast, and all my pleasures are like yesterday.” Just as Mary directly confronts death in that black hallway, and sends the detective as her surrogate to meet it, death pursues her: a few moments later she is riding a train through the city, and sees two men pretending to hold up a drunken third–but as she stares, she realizes it’s the detective, and the two men are moving the body so they can dispose of it. Yet the dance with death is primarily Jacqueline’s: when she is finally brought back into the posh sanctuary of the cult, they urge her to drink a cup of poison placed before her. This has been their voted-upon compromise: their society has a strict rule against violence, yet, in a seeming contradiction, any who defy them must die. Now if only Jacqueline would drink the poison, it would be suicide, not murder. Jacqueline, her hands extended upon the arms of the chair and tapping one finger anxiously, says “No, no, no,” like a child refusing to eat her vegetables. Nevertheless, she doesn’t run, panic, or scream. As we’ve been told, as the film has driven home determinedly, she has a longing for death. This longing, and her weak resistance to it, is the central conflict of the film. Only hours later, when her young friend breaks down in tears and begs her to drink does Jacqueline finally relent and pick up the cup, placing it to her lips, before that same friend knocks it out of her hand–she doesn’t want to be the one responsible for her friend’s death. Jacqueline is sent away, and told by the leader of the group that there will be another vote, and this time there might be violence. She leaves the tenement building and begins to walk down those familiar Val Lewton nighttime streets, waiting for a murderer to appear–and so he does, as though she had wished him into existence, and there follows a deadly chase.

What makes The Seventh Victim so shattering are its last scenes. Jacqueline fatalistically approaches Apartment #7. Another woman emerges from Apartment #8 in a bathrobe. She says, “I’m Mimi. I’m dying. I’ve been quiet, oh ever so quiet. I hardly move. And yet it keeps coming all the time, closer and closer. And I rest and I rest, and still I’m dying.”

JACQUELINE: And you don’t want to die. I’ve always wanted to die. Always.

MIMI: I’m afraid, and I’m tired of being afraid–of waiting.

JACQUELINE: Why wait?

MIMI: I’m not going to wait! I’m going out. I’m going to laugh and dance, and do all the things I used to do.

JACQUELINE: And then?

MIMI: I don’t know. (She goes back into her apartment.)

JACQUELINE: You will die.

In a way, this mirrors a minor moment earlier in the film when Jason is asked by The Dante’s proprietor to go and cheer up Mary and Gregory, to tell them jokes and make them happy. As soon as he arrives at their table, he apologizes that their very presence and demeanor has made him sad again. There seems to be no escape from despair. In the very last moment of the film, we see Mimi a second time, emerging from #8 dressed in her finest, ready to have a good time and to cast aside her worries. As she passes the closed door of #7, we hear the thumping sound of a stool toppling against the floor.

[This essay originally appeared in 2009 at my website jeffkuykendall.com.]

You can purchase the Val Lewton Collection from Amazon at the link below.