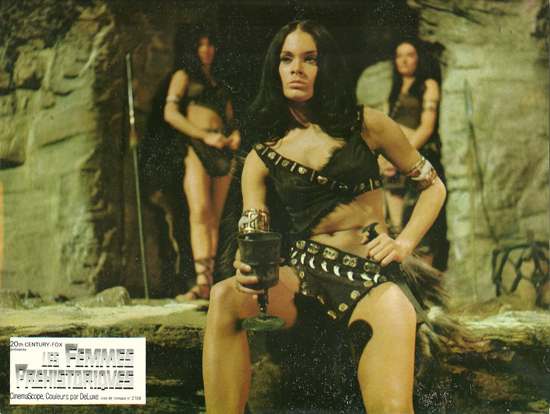

There is a single brief scene in Slave Girls (1967) which perhaps explains why the film exists. Martine Beswick, the Jamaican-born actress who posed, strutted, and wrestled her way through From Russia With Love (1963), Thunderball (1965), and One Million Years B.C. (1966), writhes upon her animal-skin-covered bed in nothing but her itty-bitty underwear, making looks toward our white hunter hero (Michael Latimer) that are not so much “come hither” as they are “I want to devour you by my gnashing white teeth.” There is a film surrounding this little moment, ninety minutes of it, but you probably won’t remember it.

There is a single brief scene in Slave Girls (1967) which perhaps explains why the film exists. Martine Beswick, the Jamaican-born actress who posed, strutted, and wrestled her way through From Russia With Love (1963), Thunderball (1965), and One Million Years B.C. (1966), writhes upon her animal-skin-covered bed in nothing but her itty-bitty underwear, making looks toward our white hunter hero (Michael Latimer) that are not so much “come hither” as they are “I want to devour you by my gnashing white teeth.” There is a film surrounding this little moment, ninety minutes of it, but you probably won’t remember it.

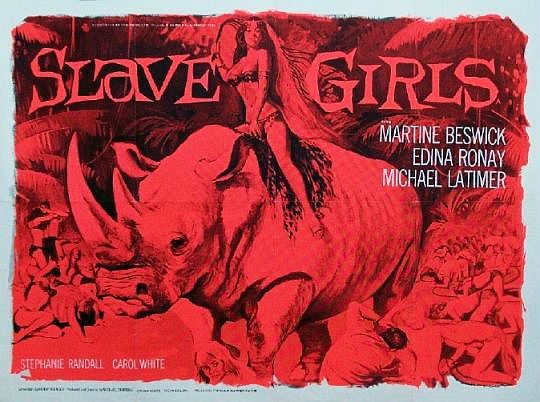

Hammer Studios filmed this B-picture hastily after the big-budget One Million Years B.C., utilizing the same fur-bikini costumes, in hopes of stretching their dollar. It’s an impoverished production, filmed on sets that look like sets, behind backdrops that look like flat and unconvincing. The special effects aren’t so special, either, unless you’re counting Ms. Beswick herself. Studio honcho Michael Carreras both wrote and directed the film, and although his efforts for Hammer were often ham-fisted, this is one of his clumsiest. The dialogue and plot are hopelessly outdated, the politics are questionable, and the direction is, at times, amateurish. Perhaps attempting to make his sets seem grander than they are, he shoots in CinemaScope, and physical and spatial distortions abound. When he lets the camera pan, the sets and actors seem to become two-dimensional and queasily stretch and ripple across the screen. This would be fine if the entire film was meant to be a dream, and I suppose you could argue that it is, since the plot features a character thrown backward in time. But I would counter-argue that the film does not know what it wants to be.

Because of the costumes, and its alternate title Prehistoric Women, the film is often grouped with Hammer’s other prehistoric adventures: its Ray Harryhausen predecessor, as well as When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) and Creatures the World Forgot (1971). But it fits more comfortably into Hammer’s H. Rider Haggard fantasy series She (1965) and Vengeance of She (1968), and earlier colonialist adventures like The Stranglers of Bombay (1959). I like some of those films, but by 1967 the formula was feeling increasingly out of time. While the civil rights struggle was still raging in the United States, over in London’s Elstree Studios Hammer was dressing black actors in generic African native costumes and making them sing and dance in choreographed numbers straight out of the 1933 King Kong. There’s also the unfortunate fact that the plot, such as it is, spirals inevitably toward a groan-worthy climax of racial panic as black men in costumes of shaggy black fur try to rape white women. This might be more troubling if the entire film weren’t so absurdly naive, as though Carreras hadn’t read anything but 1930’s pulp fiction his entire life, and regurgitated those themes into a script, with no apparent desire to modernize the sensibilities. Indeed, there are more genuinely offensive Hammer pictures in the fold (Terror of the Tongs). We can, I think, just dismiss this one as silly and dated. After all, it’s a film in which women worship a white rhino statue, a dull prop standing proudly in the center of the set as though proclaiming that money was spent on it and so we will look at it. It’s a film in which every few minutes we’re treated to a dance sequence, until one female Amazonian complains to Beswick that she just can’t dance anymore, because her heart isn’t in it (her friend was just murdered). Beswick is unmoved, so another dance begins, this to a much more downbeat tune. It’s a film in which our white-male-hunter-hero-clod-fellow becomes inexplicably smitten with just one of the many, many blonde tribeswomen, and firmly rebuffs every advance Beswick makes, even though those advances are made in overtly sexual dance numbers. In short, this is a movie that wants to be a musical. A musical directed by John Waters. Instead, it takes itself very, very seriously.

Because of the costumes, and its alternate title Prehistoric Women, the film is often grouped with Hammer’s other prehistoric adventures: its Ray Harryhausen predecessor, as well as When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) and Creatures the World Forgot (1971). But it fits more comfortably into Hammer’s H. Rider Haggard fantasy series She (1965) and Vengeance of She (1968), and earlier colonialist adventures like The Stranglers of Bombay (1959). I like some of those films, but by 1967 the formula was feeling increasingly out of time. While the civil rights struggle was still raging in the United States, over in London’s Elstree Studios Hammer was dressing black actors in generic African native costumes and making them sing and dance in choreographed numbers straight out of the 1933 King Kong. There’s also the unfortunate fact that the plot, such as it is, spirals inevitably toward a groan-worthy climax of racial panic as black men in costumes of shaggy black fur try to rape white women. This might be more troubling if the entire film weren’t so absurdly naive, as though Carreras hadn’t read anything but 1930’s pulp fiction his entire life, and regurgitated those themes into a script, with no apparent desire to modernize the sensibilities. Indeed, there are more genuinely offensive Hammer pictures in the fold (Terror of the Tongs). We can, I think, just dismiss this one as silly and dated. After all, it’s a film in which women worship a white rhino statue, a dull prop standing proudly in the center of the set as though proclaiming that money was spent on it and so we will look at it. It’s a film in which every few minutes we’re treated to a dance sequence, until one female Amazonian complains to Beswick that she just can’t dance anymore, because her heart isn’t in it (her friend was just murdered). Beswick is unmoved, so another dance begins, this to a much more downbeat tune. It’s a film in which our white-male-hunter-hero-clod-fellow becomes inexplicably smitten with just one of the many, many blonde tribeswomen, and firmly rebuffs every advance Beswick makes, even though those advances are made in overtly sexual dance numbers. In short, this is a movie that wants to be a musical. A musical directed by John Waters. Instead, it takes itself very, very seriously.

The women rule over the men, you see, and Beswick wants her new time-traveling guest to be both her lover and her servant. If he refuses, he’ll be thrown in with the other males, all chained up in a cave somewhere. But to accept means being the one who will fetch her robe after she’s done taking a prehistoric bubble bath (I’m not kidding), grind up her perfumes, and allow her to ravish him. All of this seems far too much to demand of his dignity, even though there doesn’t seem to be a great deal else to do in this far-flung land beneath the rhino-shaped mountain painted onto that backdrop over there. Meanwhile, Beswick is making one sacrifice after another to the rhino statue, passing off some of her slave girls to the aforementioned black tribesmen, who hide behind rhino masks that look like something from Julie Taymor’s Lion King musical.

So I’m not sure what this is, precisely. Time travel fantasy? Jungle adventure, prehistoric survival story, pulp fiction wet dream? Hammer was often old-fashioned, but what makes its better films so well-loved is that they would find ways to bring them up to date: make them bloody, sexy, exciting, classy, and intelligent. (Slave Girls was released on a double bill with The Devil Rides Out, which is all of those things.) Carreras’ film throws everything into the mix except for what it really needs to spark everything to life, and as a result, it tumbles over into unintentional hilarity. Which might not be such a bad thing.