During the 70’s, satirical, irreverent, and mildly smutty sketch comedy movies glutted the marketplace. Woody Allen’s Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask (1972) and the John Landis/Zucker Brothers collaboration The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977) are the two that everyone remembers, but they’re also among the few that anyone is still willing to watch. More hazily recalled are The Groove Tube (1974), The Boob Tube (1975), Tunnelvision (1976), and Can I Do It ‘Till I Need Glasses? (1977), just a few of the many disposable entries in this subgenre whose apex, it seems, was actually the TV series Saturday Night Live in 1975, which made further sketch comedy films feel somewhat unnecessary. Still, you couldn’t say “fuck” on SNL (well, Charles Rocket did, but he got fired), so I guess someone needed to keep making these things, and here’s American Raspberry.

During the 70’s, satirical, irreverent, and mildly smutty sketch comedy movies glutted the marketplace. Woody Allen’s Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Sex But Were Afraid to Ask (1972) and the John Landis/Zucker Brothers collaboration The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977) are the two that everyone remembers, but they’re also among the few that anyone is still willing to watch. More hazily recalled are The Groove Tube (1974), The Boob Tube (1975), Tunnelvision (1976), and Can I Do It ‘Till I Need Glasses? (1977), just a few of the many disposable entries in this subgenre whose apex, it seems, was actually the TV series Saturday Night Live in 1975, which made further sketch comedy films feel somewhat unnecessary. Still, you couldn’t say “fuck” on SNL (well, Charles Rocket did, but he got fired), so I guess someone needed to keep making these things, and here’s American Raspberry.

The premise is that one day every TV channel begins to air outlandish and offensive programming (the many, many skits and parodies, of course). Some Americans are amused, others are outraged; one sketch even starts a race riot. The President and his cabinet argue over what they should do, but inevitably they turn toward the screen, dazedly, and we (just as dazed and weary) watch another sketch. Eventually, the world blows up. Because of R-rated television, which is what would happen, don’t you know.

The premise is that one day every TV channel begins to air outlandish and offensive programming (the many, many skits and parodies, of course). Some Americans are amused, others are outraged; one sketch even starts a race riot. The President and his cabinet argue over what they should do, but inevitably they turn toward the screen, dazedly, and we (just as dazed and weary) watch another sketch. Eventually, the world blows up. Because of R-rated television, which is what would happen, don’t you know.

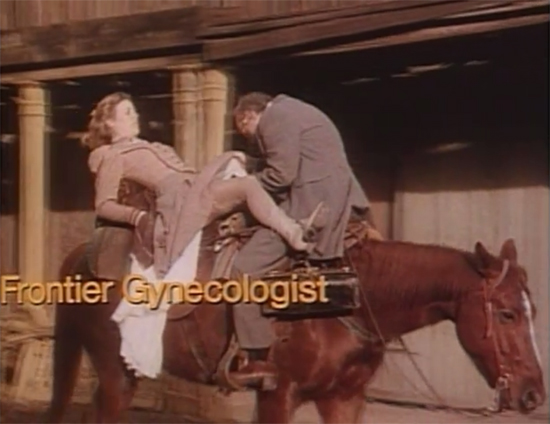

I can sum up the problem with American Raspberry very efficiently: it’s not funny. Or, at least, about 90% of it is not. The sketch show is a sturdy old format for a reason, which is that if a joke does not work, you can move on to the next, and then the one after that. You don’t need to commit to anything for too long. Not all of Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969-1974) was hysterical, but proportionally they got it right. Similarly, the Zucker Brothers’ gags in The Kentucky Fried Movie and Airplane (1980) are inconsistent as hell, but what did work was strong enough that you remember it. American Raspberry cannot achieve lift-off. Through one sketch after another, nothing terribly funny occurs. Part of the problem is that the parodies are not much more than parodies: you are meant to recognize that a popular commercial is being spoofed, and that’s supposed to be enough. (This is still an issue in commercial comedies today, notably Scary Movie and all its bastard children.) The other problem is that the writers (Stephen Feinberg, John Baskin, Roger Shulman, and Bradley R. Swirnoff, who also directed) are too easily satisfied with the “fuck you” joke. The “fuck you” joke is pretty easy to tell. Basically, set it up with whatever you want; the punchline is always “fuck you.” Applied with discretion, this humor can work. But otherwise it tends to fall flat, and the reason is simple: it’s not terribly clever.

Take the first sketch, a commercial for “Trans Puerto Rico.” Our hostess escorts us through the plane, and we’re treated to gags such as: the plane has a ceiling fan instead of air conditioning; the pilots are drinking tequila; there is a giant crucifix hanging on the wall; a passenger is stowing the dead body of a loved one in the overhead compartment; a man brings a chicken aboard, and when the stewardess tells him he has to leave it behind, he immediately breaks its neck. Ha ha, Puerto Ricans are funny, even on an airplane. Fuck you! But this passes as one of the stronger bits in the film, because at least it’s a concept that’s developed a few feet past its original premise. Most are simply super-brief gags that don’t actually seem to develop into a complete comedy premise. For example, there’s a commercial for a religious game show, with all the contestants lined up Last Supper-style. The narrator says: “Hi, this is Johnny Jones, a religious fantatic who is crucified and then rises from the dead! Do you buy that? See if our contestants will, tonight on ‘Hook, Line & Sinker.'” End sketch. And fuck you.

Hey, it was the 70’s. The counterculture had grown cynical, and a lot of the humor was like this: offensive for the sake of being offensive, with no “jokes” per se. You can trace this back to the underground comix of the 60’s, many of which were juvenile, sexist, and racist; but that was the point. They were intended to be transgressive – to jolt you awake, man. About a year ago I visited an exhibit of 60’s and 70’s comix art at a local museum, and those peering through the glass to read the comic strip panels were either aghast, offended, or giggling nervously, as though afraid someone might catch them enjoying it. (Well, there were others who were appraising each page with all the seriousness of studying a Monet, which is perhaps the only inappropriate way of approaching R. Crumb drawings of little men sodomizing headless giantesses.) After spending a couple of hours in the exhibit, I was starting to feel a bit exhausted myself; there was also a feeling of: okay, every taboo has been violated…so what do you say now? And that leads you to the 70’s, with the censorship of the Hays code long forgotten and pornography prevalent, and even briefly respectable; the shock was starting to wear off, and something needed to take its place. From the influential Harvard Lampoon to the work of experimental comedians like Andy Kaufman and Michael O’Donoghue, you can feel a kind of exploration taking place, a trailblazing which, in retrospect, had to occur, in order to lead, decades on, to the extra-meta subversiveness of The Colbert Report and South Park. In the 70’s, comedians were asking: what’s out of bounds, if anything? What if you don’t have punchlines; what if you don’t have a joke?

Hey, it was the 70’s. The counterculture had grown cynical, and a lot of the humor was like this: offensive for the sake of being offensive, with no “jokes” per se. You can trace this back to the underground comix of the 60’s, many of which were juvenile, sexist, and racist; but that was the point. They were intended to be transgressive – to jolt you awake, man. About a year ago I visited an exhibit of 60’s and 70’s comix art at a local museum, and those peering through the glass to read the comic strip panels were either aghast, offended, or giggling nervously, as though afraid someone might catch them enjoying it. (Well, there were others who were appraising each page with all the seriousness of studying a Monet, which is perhaps the only inappropriate way of approaching R. Crumb drawings of little men sodomizing headless giantesses.) After spending a couple of hours in the exhibit, I was starting to feel a bit exhausted myself; there was also a feeling of: okay, every taboo has been violated…so what do you say now? And that leads you to the 70’s, with the censorship of the Hays code long forgotten and pornography prevalent, and even briefly respectable; the shock was starting to wear off, and something needed to take its place. From the influential Harvard Lampoon to the work of experimental comedians like Andy Kaufman and Michael O’Donoghue, you can feel a kind of exploration taking place, a trailblazing which, in retrospect, had to occur, in order to lead, decades on, to the extra-meta subversiveness of The Colbert Report and South Park. In the 70’s, comedians were asking: what’s out of bounds, if anything? What if you don’t have punchlines; what if you don’t have a joke?

American Raspberry heads down that trail not like a pioneer, but like a particularly grating follower a few steps behind, who’s first on the list to get eaten for supper should the food supply run out. The film is eager to offend, but as though that were the only prize. It’s like Michael Richards using the n-word and thinking that makes him Lenny Bruce.

But I’m being unfair. There are a couple of funny things here. I took some amusement out of the following sketch, but that might only be because it has Harry Shearer in it, in a very early cameo. I’m still uncertain if it’s funny without the Harry Shearer, or without the novelty of containing a face I recognize. But I was halfway through this film and starting to get desperate.

A couple of sketches just begin to land a joke before they cut away, or spoil it with an unfunny punchline. One bit, involving “5th-year abortions,” depicts a married couple happily giving away their rambunctious five-year-old to a death squad that arrives at their home. The performances almost elevate the material. Ditto the “sexual perversions” telethon, in which, at one point, the teary, cross-dressing emcee begins to get whipped by his co-host, and he mutters to her miserably, “Don’t try to cheer me up.” Some sketches are saved by hasty editing, such as the “fire the handicapped” commercial, or a bizarre, seconds-long bit featuring a poodle religious leader.

The single funniest scene in the film – the one which actually made me laugh, a function which I’d worried my body had forgotten how to perform – is a commercial for a menstrual pontoon called “Clampex.” I showed it to my wife the next morning to make sure that it was funny, and that I hadn’t just laughed as some kind of survival mechanism to make it to the end of the film. She confirmed that it was not a symptom of psychosis, and that there is actual humorous content in this clip.

Look, look, it’s comedy! Note the (just brief enough to be perfectly timed) diagram of the vagina, sufficiently intimidating, and including mythological beasts Scylla and Charybdis (as well as cannelloni). And the beautifully pointless direction to “pretend the room is a huge vagina.” And: “Think of it as a puzzle. Relax, and begin all over.” Comedy! The stuff of life – or, at least, what motion picture comedies are actually intended to contain!

During the ending credits, I was dismayed, if not surprised, to learn that this was a piece borrowed from National Lampoon, and written by Emily Prager, who was not one of the American Raspberry screenwriters. That’s right, the one thing in the film I find to be truly clever and funny, and it’s not even original to this film.

Oh well. If all I got out of this seventy-minute film was one minute of comedy gold, perhaps that’s a bargain. (No, no, it isn’t.)