With the surrealist Western El Topo (1970), the Chilean-born Alejandro Jodorowsky suddenly found himself an overnight (or, rather, midnight) sensation at the age of 41. His life had been one of adventures, spiked with a few tall tales; it’s known that he formed a theater troupe in Chile before traveling to Paris, where he worked with Marcel Marceau, writing some of that performer’s most famous mime performances; he even directed Maurice Chevalier on the stage, and co-founded the confrontational Panic movement with playwright Fernando Arrabal and artist/novelist Roland Topor, before relocating to Mexico and directing a film of Arrabal’s play Fando y Lis (1967), which reportedly caused a riot at its film festival premiere. And yet he did not fully emerge as a cause célèbre until El Topo became the first “midnight movie,” meaning that was the only time you could see it (at the Elgin Cinema in New York City); not since the films of Andy Warhol did underground filmmaking, and its pot-smoke-choked late night screenings, garner such mainstream attention. Ritualistically, attendees to El Topo would take their drug of choice and blink their eyes at the sex, violence, and symbolism on display in Jodorowsky’s film, then stumble into the streets at two in the morning wondering at the mystery of it all. Jodorowsky, who wrote, directed, and scored the film, significantly starred in it as well, casting himself as a gunman in black, riding his horse through a vast desert (at first with his naked young son in tow), dueling with Zen masters and eventually undergoing a physical and spiritual transformation before taking on Society with a machine gun in his hands. The film was political, satirical, overtly surrealist, comic, horrific, exciting, absurd. It appropriated icons and elements of Buddhism and Christianity. The dubbed dialogue featured lines such as, “I let the bullets pass through the emptiness of my heart.” What did it all mean? He wasn’t short on answers in the El Topo LP liner notes (released by Apple Records), and in several Dali-esque interviews. He explained that for the scene in which a woman drinks from a spring that miraculously erupts from a stone in the desert, he requested the stone be carved to resemble his own penis. And it does look like a penis. That girl is clearly letting her face get sprayed by a giant penis stone…in one three-second scene, surrounded by a hundred other memorable spectacles that pass rapid-fire in this genuinely psychedelic Western. Those sights did stick in the consciousness, and the obsessive symbology of the film, combined with Jodorowsky’s passionate storytelling, did form a cinematic impact. This, combined with the inescapable aura of mysticism, helped foster the cult.

With the surrealist Western El Topo (1970), the Chilean-born Alejandro Jodorowsky suddenly found himself an overnight (or, rather, midnight) sensation at the age of 41. His life had been one of adventures, spiked with a few tall tales; it’s known that he formed a theater troupe in Chile before traveling to Paris, where he worked with Marcel Marceau, writing some of that performer’s most famous mime performances; he even directed Maurice Chevalier on the stage, and co-founded the confrontational Panic movement with playwright Fernando Arrabal and artist/novelist Roland Topor, before relocating to Mexico and directing a film of Arrabal’s play Fando y Lis (1967), which reportedly caused a riot at its film festival premiere. And yet he did not fully emerge as a cause célèbre until El Topo became the first “midnight movie,” meaning that was the only time you could see it (at the Elgin Cinema in New York City); not since the films of Andy Warhol did underground filmmaking, and its pot-smoke-choked late night screenings, garner such mainstream attention. Ritualistically, attendees to El Topo would take their drug of choice and blink their eyes at the sex, violence, and symbolism on display in Jodorowsky’s film, then stumble into the streets at two in the morning wondering at the mystery of it all. Jodorowsky, who wrote, directed, and scored the film, significantly starred in it as well, casting himself as a gunman in black, riding his horse through a vast desert (at first with his naked young son in tow), dueling with Zen masters and eventually undergoing a physical and spiritual transformation before taking on Society with a machine gun in his hands. The film was political, satirical, overtly surrealist, comic, horrific, exciting, absurd. It appropriated icons and elements of Buddhism and Christianity. The dubbed dialogue featured lines such as, “I let the bullets pass through the emptiness of my heart.” What did it all mean? He wasn’t short on answers in the El Topo LP liner notes (released by Apple Records), and in several Dali-esque interviews. He explained that for the scene in which a woman drinks from a spring that miraculously erupts from a stone in the desert, he requested the stone be carved to resemble his own penis. And it does look like a penis. That girl is clearly letting her face get sprayed by a giant penis stone…in one three-second scene, surrounded by a hundred other memorable spectacles that pass rapid-fire in this genuinely psychedelic Western. Those sights did stick in the consciousness, and the obsessive symbology of the film, combined with Jodorowsky’s passionate storytelling, did form a cinematic impact. This, combined with the inescapable aura of mysticism, helped foster the cult.

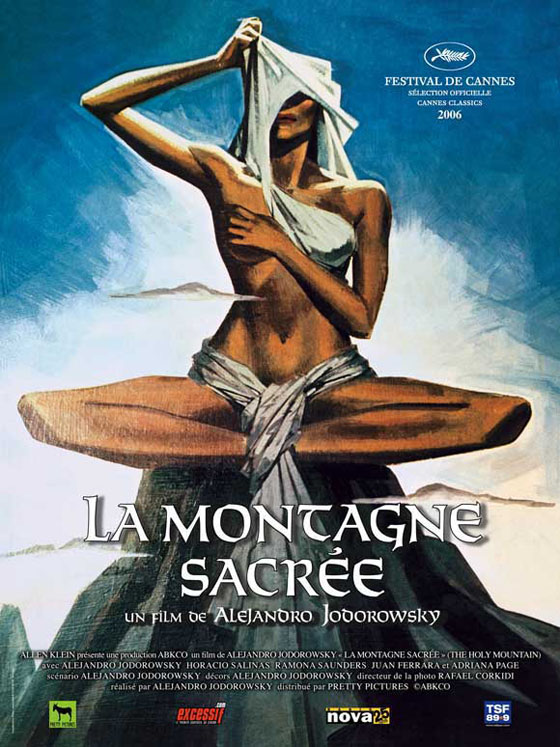

Detractors argued that the film’s gestures toward profundity disguised the fact that it wasn’t particularly profound. Regardless, Jodorowsky had made a name for himself, and people began to look at him in a different way. He was now a guru; they wanted wisdom. And they wanted to go on a journey with him to find more answers – the Truth, man. So he had to make The Holy Mountain next, and The Holy Mountain is a film which only makes a lick of sense if you understand this. There had never been a film like this before, and there never will be again. Such a large-scale, free-form head trip, beautiful and ugly, spellbinding and nightmarish, brilliant and head-slappingly naive, could only have arrived on the heels of El Topo‘s unexpected success. It could only have emerged on the flush of a flattered ego (in particular, a surrealist’s flattered ego). It could only have arrived in the early 1970’s, when cinema was seeking to break every existing taboo on-screen. It could only have arrived from Jodorowsky’s boundless imagination, and he never again would be presented with such an opportunity to let it all hang out.

Detractors argued that the film’s gestures toward profundity disguised the fact that it wasn’t particularly profound. Regardless, Jodorowsky had made a name for himself, and people began to look at him in a different way. He was now a guru; they wanted wisdom. And they wanted to go on a journey with him to find more answers – the Truth, man. So he had to make The Holy Mountain next, and The Holy Mountain is a film which only makes a lick of sense if you understand this. There had never been a film like this before, and there never will be again. Such a large-scale, free-form head trip, beautiful and ugly, spellbinding and nightmarish, brilliant and head-slappingly naive, could only have arrived on the heels of El Topo‘s unexpected success. It could only have emerged on the flush of a flattered ego (in particular, a surrealist’s flattered ego). It could only have arrived in the early 1970’s, when cinema was seeking to break every existing taboo on-screen. It could only have arrived from Jodorowsky’s boundless imagination, and he never again would be presented with such an opportunity to let it all hang out.

Even if Jodorowsky does again get the keys to the kingdom – he is not the same man. The younger Jodorowsky could be chauvinist, arrogant, self-serious. The older Jodorowsky – the prolific author behind graphic novels such as The Metabarons and Madwoman of the Sacred Heart; the “psychomagician” and Tarot card expert – is humbler and warmer (I’ve met the man and can attest). He is not, or at least is no longer, the man portrayed so harshly in Hoberman and Rosenbaum’s seminal book Midnight Movies. His more recent fictions, from Santa Sangre (1989) through his comics work, reflect an artist who would rather ask questions than deliver, or dictate, The Answer to a flock. Much of his present work is profound, and typically heartfelt and moving. When I saw Jodorowsky introduce The Holy Mountain several years ago at a screening in Toronto, he seemed slightly embarrassed by the film; afterward, introducing the second half of the double feature (Santa Sangre), he assured everyone “I like this one better” (or words to the effect). When I was younger, I liked The Holy Mountain more. I found it mind-blowing. As I grow older, I find Santa Sangre to be the greater work. But both films are the work of a man passionate about pushing the boundaries of cinematic storytelling. The younger, brash and bold Jodorowsky was a force of nature, and thank the Tarot he made The Holy Mountain when he got the chance.

Even if Jodorowsky does again get the keys to the kingdom – he is not the same man. The younger Jodorowsky could be chauvinist, arrogant, self-serious. The older Jodorowsky – the prolific author behind graphic novels such as The Metabarons and Madwoman of the Sacred Heart; the “psychomagician” and Tarot card expert – is humbler and warmer (I’ve met the man and can attest). He is not, or at least is no longer, the man portrayed so harshly in Hoberman and Rosenbaum’s seminal book Midnight Movies. His more recent fictions, from Santa Sangre (1989) through his comics work, reflect an artist who would rather ask questions than deliver, or dictate, The Answer to a flock. Much of his present work is profound, and typically heartfelt and moving. When I saw Jodorowsky introduce The Holy Mountain several years ago at a screening in Toronto, he seemed slightly embarrassed by the film; afterward, introducing the second half of the double feature (Santa Sangre), he assured everyone “I like this one better” (or words to the effect). When I was younger, I liked The Holy Mountain more. I found it mind-blowing. As I grow older, I find Santa Sangre to be the greater work. But both films are the work of a man passionate about pushing the boundaries of cinematic storytelling. The younger, brash and bold Jodorowsky was a force of nature, and thank the Tarot he made The Holy Mountain when he got the chance.

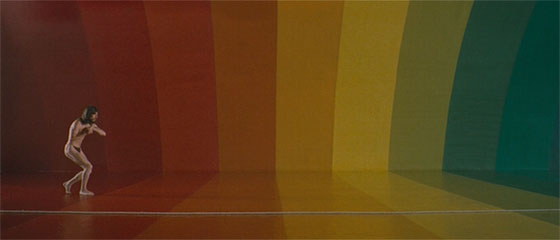

It’s the story of a thief – it’s implied he is the Fool of the Tarot – who stumbles deliriously through a decadent society possibly in South America, possibly in Mexico, possibly in the United States (as in El Topo, we’re occupying a strictly metaphorical realm). At the beginning of the film, he’s lying unconscious in a pool of his own urine, his face covered in flies. Subsequently he’s dragged away by a mob of children with painted-green penises and crucified; he frees himself and journeys with a limbless man through a city that’s been apparently occupied by a colonial power, and commercialized for tourism. Before a crowd of spectators, the conquest of Mexico is restaged using iguanas dressed up as Aztecs and toads in conquistador helmets. Armed soldiers occupy every street, and as one casually rapes a tourist, another tourist cheerily has his picture taken with the both of them. Stacks of bloody bodies are carted through the street. Catholicism has become a boom trade, we can surmise, since fat men dressed as Roman centurions hawk their Christian wares on the street; our protagonist is even abducted and covered in plaster, so he can be the model for a new lifesize Christ that can be mass-produced and sold. He encounters prostitutes, all dressed identically, one of them just a child, and another a chimp. (Or perhaps it’s just a pet of the prostitutes; I’ve never been sure.) And he at last comes to a great red tower in the center of the city, featureless except for a round hole at its peak. Some holy man lives within the tower, and by a long anchor lowered from that portal above, he trades food for gold. Eager to know the source of the gold, the Thief jumps aboard the anchor and rides it to the top of the tower. He enters a vast, rainbow-colored passage, at the end of it Jodorowsky himself, seated upon a throne of stuffed rams with enormous testicles. He’s dressed now in white instead of black, in elevator shoes and a wide-brimmed hat that nearly covers his eyes. To one side of Jodorowsky is a naked black woman covered in tattoos and body ornaments, including a silver skullcap; to the other, a camel. As though they were clues to unravel a metaphysical mystery novel, Jodorowsky quickly cuts in close-ups of the various symbols painted upon the woman’s skin, as well as those dangling ram testicles. It’s not enough to stuff his films with bizarre and seemingly random images: he also must display them to you as though proudly guiding you through his own little Mütter Museum.

It’s the story of a thief – it’s implied he is the Fool of the Tarot – who stumbles deliriously through a decadent society possibly in South America, possibly in Mexico, possibly in the United States (as in El Topo, we’re occupying a strictly metaphorical realm). At the beginning of the film, he’s lying unconscious in a pool of his own urine, his face covered in flies. Subsequently he’s dragged away by a mob of children with painted-green penises and crucified; he frees himself and journeys with a limbless man through a city that’s been apparently occupied by a colonial power, and commercialized for tourism. Before a crowd of spectators, the conquest of Mexico is restaged using iguanas dressed up as Aztecs and toads in conquistador helmets. Armed soldiers occupy every street, and as one casually rapes a tourist, another tourist cheerily has his picture taken with the both of them. Stacks of bloody bodies are carted through the street. Catholicism has become a boom trade, we can surmise, since fat men dressed as Roman centurions hawk their Christian wares on the street; our protagonist is even abducted and covered in plaster, so he can be the model for a new lifesize Christ that can be mass-produced and sold. He encounters prostitutes, all dressed identically, one of them just a child, and another a chimp. (Or perhaps it’s just a pet of the prostitutes; I’ve never been sure.) And he at last comes to a great red tower in the center of the city, featureless except for a round hole at its peak. Some holy man lives within the tower, and by a long anchor lowered from that portal above, he trades food for gold. Eager to know the source of the gold, the Thief jumps aboard the anchor and rides it to the top of the tower. He enters a vast, rainbow-colored passage, at the end of it Jodorowsky himself, seated upon a throne of stuffed rams with enormous testicles. He’s dressed now in white instead of black, in elevator shoes and a wide-brimmed hat that nearly covers his eyes. To one side of Jodorowsky is a naked black woman covered in tattoos and body ornaments, including a silver skullcap; to the other, a camel. As though they were clues to unravel a metaphysical mystery novel, Jodorowsky quickly cuts in close-ups of the various symbols painted upon the woman’s skin, as well as those dangling ram testicles. It’s not enough to stuff his films with bizarre and seemingly random images: he also must display them to you as though proudly guiding you through his own little Mütter Museum.

The Master – we’ll call him that, for no one here has a name – duels with and quickly disarms the Thief. Briefly, we seem to be in a Bruce Lee movie. The Master subdues the Thief by tapping him sharply at various points upon his body, to a chiming noise; and then Jodorowsky begins to talk. We’re now about half an hour into the film, and we finally have dialogue. Jodorowsky provides his own voice, and struggles with his English (as he does to this day); he annunciates his words laboriously, while sounding just a bit like Peter Lorre, and with a haircut and moustache that anticipate Gallagher. For a guru, he’s awfully goofy. He immediately gets on with making over the Thief, which begins with cutting out an evil giant slug that was living in the back of his neck (a la The Hidden), giving him a bath in a spa occupied by a hippopotamus, and scrubbing his anus in extreme close-up. He asks the Thief, “Do you want gold?”, which receives an enthusiastic reply. Jodorowsky then has the man defecate, and we see every step in the alchemical process to transform that shit into a couple of lumps of gold. “We can turn ourselves into gold,” Jodorowsky says. This theme – of self-transformation, and remaking ourselves until we can reach our full potential – recurs in pretty much all of Jodorowsky’s work post-El Topo. But only in The Holy Mountain do we get the anus-scrubbing, so relish it.

The Master – we’ll call him that, for no one here has a name – duels with and quickly disarms the Thief. Briefly, we seem to be in a Bruce Lee movie. The Master subdues the Thief by tapping him sharply at various points upon his body, to a chiming noise; and then Jodorowsky begins to talk. We’re now about half an hour into the film, and we finally have dialogue. Jodorowsky provides his own voice, and struggles with his English (as he does to this day); he annunciates his words laboriously, while sounding just a bit like Peter Lorre, and with a haircut and moustache that anticipate Gallagher. For a guru, he’s awfully goofy. He immediately gets on with making over the Thief, which begins with cutting out an evil giant slug that was living in the back of his neck (a la The Hidden), giving him a bath in a spa occupied by a hippopotamus, and scrubbing his anus in extreme close-up. He asks the Thief, “Do you want gold?”, which receives an enthusiastic reply. Jodorowsky then has the man defecate, and we see every step in the alchemical process to transform that shit into a couple of lumps of gold. “We can turn ourselves into gold,” Jodorowsky says. This theme – of self-transformation, and remaking ourselves until we can reach our full potential – recurs in pretty much all of Jodorowsky’s work post-El Topo. But only in The Holy Mountain do we get the anus-scrubbing, so relish it.

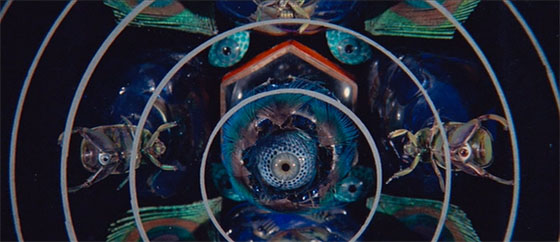

The film is divided informally into three acts, each of which takes approximately forty minutes. Act Two is introduced when the Master leads the Thief into a circular chamber occupied by wax statues representing seven individuals who have come seeking enlightenment. These characters, who identify themselves with different planets (thus confusing me upon my first viewing, as I mistakenly thought they were from those planets) narrate their own tales. What follows is one remarkable image after another, as suddenly the film kicks into a higher gear, and gains a vitality – and wit – that should wake up all the glassy-eyed stoners in the audience. An industrial tycoon manufactures weapons of war, catering to all ethnicities and religions with devices such as a Chanukah gun and a crucifix pistol. A nation is taught to abhor its war enemy through manufactured propaganda (including, in an in-joke, a comic book published by “Panic Comics”), and more direct and abusive brainwashing of its children. A pleasure-seeker keeps a concubine of secretaries, whom he impregnates on rotation, while producing in his factory false faces and body parts for the vain to display. A millionaire oversees art projects and inventions including a robot sex machine, an almost Cubist representation of a vagina, which orgasms only when properly stimulated by a giant rod, and promptly creates an adorable robot baby.

The film is divided informally into three acts, each of which takes approximately forty minutes. Act Two is introduced when the Master leads the Thief into a circular chamber occupied by wax statues representing seven individuals who have come seeking enlightenment. These characters, who identify themselves with different planets (thus confusing me upon my first viewing, as I mistakenly thought they were from those planets) narrate their own tales. What follows is one remarkable image after another, as suddenly the film kicks into a higher gear, and gains a vitality – and wit – that should wake up all the glassy-eyed stoners in the audience. An industrial tycoon manufactures weapons of war, catering to all ethnicities and religions with devices such as a Chanukah gun and a crucifix pistol. A nation is taught to abhor its war enemy through manufactured propaganda (including, in an in-joke, a comic book published by “Panic Comics”), and more direct and abusive brainwashing of its children. A pleasure-seeker keeps a concubine of secretaries, whom he impregnates on rotation, while producing in his factory false faces and body parts for the vain to display. A millionaire oversees art projects and inventions including a robot sex machine, an almost Cubist representation of a vagina, which orgasms only when properly stimulated by a giant rod, and promptly creates an adorable robot baby.

A famed architect reveals his new plans to handle overpopulation: condominiums that fit snugly around each individual, and just happen to resemble coffins; they can be efficiently stacked in city blocks. A warrior of a police state, carrying a revolver larger than he is, struts into the center of a vast throng and castrates a boy strapped to a table. He then conducts us into his private chamber, filled with jars of testicles lined up on shelves, a collection which, he insists, are vital to the nation’s strength. We see soldiers slaughter unarmed protestors, except that the killings are deliberately staged (fake blood squirts out of tubes; a mannequin is decapitated, and a mechanical skull head pops up to take its place). In a segment that could have been directed by John Waters, a fat naked woman sits high atop a toilet that extends toward the ceiling, and complains to her husband – lying in bed next to the toilet – that their window is the wrong size. And on and on and on.

A famed architect reveals his new plans to handle overpopulation: condominiums that fit snugly around each individual, and just happen to resemble coffins; they can be efficiently stacked in city blocks. A warrior of a police state, carrying a revolver larger than he is, struts into the center of a vast throng and castrates a boy strapped to a table. He then conducts us into his private chamber, filled with jars of testicles lined up on shelves, a collection which, he insists, are vital to the nation’s strength. We see soldiers slaughter unarmed protestors, except that the killings are deliberately staged (fake blood squirts out of tubes; a mannequin is decapitated, and a mechanical skull head pops up to take its place). In a segment that could have been directed by John Waters, a fat naked woman sits high atop a toilet that extends toward the ceiling, and complains to her husband – lying in bed next to the toilet – that their window is the wrong size. And on and on and on.

Act Three: each of these characters now arrive at the tower by helicopter, and after burning their wax replicas, depart on a quest for the Holy Mountain – a place supposedly occupied by wise men. The Master and his followers intend to steal their secret knowledge (possibly by force), thus attaining enlightenment. The Thief joins them; and trailing closely is one of the city prostitutes, apparently in love with the Thief, and still leading her chimp by the hand. Shaved and fit, the followers of the Master undergo several rituals on the way to the Holy Mountain, including casting their consciousness into animals, meditating atop ancient ruins, and overcoming their own psychological burdens (turns out that limbless dwarf doesn’t really exist, but is the Thief’s own psychic baggage which he must literally drown).

Act Three: each of these characters now arrive at the tower by helicopter, and after burning their wax replicas, depart on a quest for the Holy Mountain – a place supposedly occupied by wise men. The Master and his followers intend to steal their secret knowledge (possibly by force), thus attaining enlightenment. The Thief joins them; and trailing closely is one of the city prostitutes, apparently in love with the Thief, and still leading her chimp by the hand. Shaved and fit, the followers of the Master undergo several rituals on the way to the Holy Mountain, including casting their consciousness into animals, meditating atop ancient ruins, and overcoming their own psychological burdens (turns out that limbless dwarf doesn’t really exist, but is the Thief’s own psychic baggage which he must literally drown).

Once they reach Lotus Island, where the Holy Mountain lies, they encounter the Pantheon Bar, a decadent tourist trap of distractions, including one man who, X-Men-like, can teleport himself through the mountain within seconds. “I have conquered the Holy Mountain!” he declares. When asked what the summit is like, he scoffs: “I can only go horizontally.” Writing this just now, I realized why I liked these Act Three moments so much when I first watched the film. Subconsciously I was reminded of Pilgrim’s Progress, the Christian allegory which I read, in a simplified text, as a God-fearing child. In that book, the main character (“Christian”) is offered many temptations on the way to Paradise, each of them a character or peril given an explicitly allegorical name. The Pantheon Bar is like something Christian might have encountered, another distraction planted by the Devil. The Holy Mountain, perversely, appealed to my younger, religious self, while stimulating my twentysomething identity with its shock-value sights and spectacle. I was also, on that first viewing, impressed by its memorable coda. Jodorowsky, having attained, with his followers, the table of the wise men (actually just stuffed dummies) at the top of the Holy Mountain, declares, “All is Maya! Pan back, camera!” – and reveals all the crew members who had been hiding just out of frame. We see the boom mikes and the other cameras. “This is a film!” Jodorowsky grins toward us, before urging his followers to forget their quest for sacred MacGuffins and to experience life directly instead. “Goodbye to the Holy Mountain. Real life awaits us.”

Once they reach Lotus Island, where the Holy Mountain lies, they encounter the Pantheon Bar, a decadent tourist trap of distractions, including one man who, X-Men-like, can teleport himself through the mountain within seconds. “I have conquered the Holy Mountain!” he declares. When asked what the summit is like, he scoffs: “I can only go horizontally.” Writing this just now, I realized why I liked these Act Three moments so much when I first watched the film. Subconsciously I was reminded of Pilgrim’s Progress, the Christian allegory which I read, in a simplified text, as a God-fearing child. In that book, the main character (“Christian”) is offered many temptations on the way to Paradise, each of them a character or peril given an explicitly allegorical name. The Pantheon Bar is like something Christian might have encountered, another distraction planted by the Devil. The Holy Mountain, perversely, appealed to my younger, religious self, while stimulating my twentysomething identity with its shock-value sights and spectacle. I was also, on that first viewing, impressed by its memorable coda. Jodorowsky, having attained, with his followers, the table of the wise men (actually just stuffed dummies) at the top of the Holy Mountain, declares, “All is Maya! Pan back, camera!” – and reveals all the crew members who had been hiding just out of frame. We see the boom mikes and the other cameras. “This is a film!” Jodorowsky grins toward us, before urging his followers to forget their quest for sacred MacGuffins and to experience life directly instead. “Goodbye to the Holy Mountain. Real life awaits us.”

I’ve seen the film a few times since then, and my impressions have changed somewhat. But my first viewing was also colored by the rarity of the picture. Prior to its DVD release a few years ago, The Holy Mountain, like its companion El Topo, was almost impossible to see in the States. Once the internet and eBay arrived, one could order a tape, which would be either a bootleg or an import. I watched a copy rented from the great Scarecrow Video in Seattle, with a hefty deposit (should I lose this prized copy); it was a VHS from Japan, with censorship clouds that obscured those frequently-displayed genitals. Watching both The Holy Mountain and El Topo – in those days – felt like being initiated into a secret society. These were films you had heard about, but it was a privilege to be able to watch them. Allen Klein, John Lennon’s promoter and the American distributor of the films, was still locked in a decades-long personal feud with Jodorowsky, and he refused to release the films on video. The two men hated one another with vitriol. Jodorowsky claimed that Klein was destroying prints of the films; that he was a “murderer” because of it. (A couple of years before Klein’s death, the two held a meeting where these hostile feelings melted immediately; they became friends once more, and Klein agreed to release the films on DVD.) So if you got to see either of those movies in those days, you were invested in the experience. Watching them was an event. That Jodorowsky delivered on the spectacle made the event even more special; you tried to describe it to your friends. “It’s the most amazing film, if only you could see it…”

I’ve seen the film a few times since then, and my impressions have changed somewhat. But my first viewing was also colored by the rarity of the picture. Prior to its DVD release a few years ago, The Holy Mountain, like its companion El Topo, was almost impossible to see in the States. Once the internet and eBay arrived, one could order a tape, which would be either a bootleg or an import. I watched a copy rented from the great Scarecrow Video in Seattle, with a hefty deposit (should I lose this prized copy); it was a VHS from Japan, with censorship clouds that obscured those frequently-displayed genitals. Watching both The Holy Mountain and El Topo – in those days – felt like being initiated into a secret society. These were films you had heard about, but it was a privilege to be able to watch them. Allen Klein, John Lennon’s promoter and the American distributor of the films, was still locked in a decades-long personal feud with Jodorowsky, and he refused to release the films on video. The two men hated one another with vitriol. Jodorowsky claimed that Klein was destroying prints of the films; that he was a “murderer” because of it. (A couple of years before Klein’s death, the two held a meeting where these hostile feelings melted immediately; they became friends once more, and Klein agreed to release the films on DVD.) So if you got to see either of those movies in those days, you were invested in the experience. Watching them was an event. That Jodorowsky delivered on the spectacle made the event even more special; you tried to describe it to your friends. “It’s the most amazing film, if only you could see it…”

So the DVD release – and now, my God, hi-def Blu-Rays – of pristine prints of both pictures has somewhat demythologized the films. They are no longer rare, but they are still special. El Topo, for all its flaws, is still a memorable experience. The Holy Mountain, too, is an experience – perhaps more of an experience than a film. Jodorowsky took his cast and crew on a journey, and the journey became the story; it’s only natural, in the final frames, that he has the camera pan back and let the fiction cross over into documentary with fluidity. The storytelling falters – and is sometimes nonexistent – but one gets the feeling that Jodorowsky is so eager to cram every single one of his wild ideas into the film that he doesn’t really care about narrative structure. He filmed it as though it were the last film he’d ever get a chance to make. Cinematic history has given us a few of those go-for-brokes (Southland Tales springs to mind), but they are rarely as jaw-dropping as The Holy Mountain. It’s a grimy film at times – and when I watch it, I swear I can smell the body odor drifting from the screen, even after the ritualized bathing. The film, for all its splendor, frequently revels in ugliness. (One of the scenes toward the end of the film has truly disturbed me for years, actually; it’s as though Jodorowsky probed a particularly sensitive psychic area that even I don’t understand.) But the film is one crazy idea after another, impeccably shot, and delivered on a scale that no midnight moviemaker ought to have had the budget to achieve. The eyes, they pop. He climbed the mountain, and that he got there is an achievement. Take your drug of choice and climb with him, but mind the steep drop on your way back.

So the DVD release – and now, my God, hi-def Blu-Rays – of pristine prints of both pictures has somewhat demythologized the films. They are no longer rare, but they are still special. El Topo, for all its flaws, is still a memorable experience. The Holy Mountain, too, is an experience – perhaps more of an experience than a film. Jodorowsky took his cast and crew on a journey, and the journey became the story; it’s only natural, in the final frames, that he has the camera pan back and let the fiction cross over into documentary with fluidity. The storytelling falters – and is sometimes nonexistent – but one gets the feeling that Jodorowsky is so eager to cram every single one of his wild ideas into the film that he doesn’t really care about narrative structure. He filmed it as though it were the last film he’d ever get a chance to make. Cinematic history has given us a few of those go-for-brokes (Southland Tales springs to mind), but they are rarely as jaw-dropping as The Holy Mountain. It’s a grimy film at times – and when I watch it, I swear I can smell the body odor drifting from the screen, even after the ritualized bathing. The film, for all its splendor, frequently revels in ugliness. (One of the scenes toward the end of the film has truly disturbed me for years, actually; it’s as though Jodorowsky probed a particularly sensitive psychic area that even I don’t understand.) But the film is one crazy idea after another, impeccably shot, and delivered on a scale that no midnight moviemaker ought to have had the budget to achieve. The eyes, they pop. He climbed the mountain, and that he got there is an achievement. Take your drug of choice and climb with him, but mind the steep drop on your way back.