“I’m William Castle, the director of the film you’re about to see. I feel obligated to warn you that some of the sensations, some of the physical reactions which the actors on the screen will feel, will also be experienced, for the first time in motion picture history, by certain members of this audience. I say ‘certain members’ because some people are more sensitive to these mysterious electronic impulses than others. These unfortunate, sensitive people will at times feel a strange tingling sensation. Others will feel it less strongly. But don’t be alarmed: you can protect yourself. At any time you are conscious of a tingling sensation, you can obtain immediate relief by screaming. Don’t be embarrassed to open your mouth and let it rip with all you’ve got, because the person in the seat right next to you will probably be screaming too. And remember this: a scream at the right time may save your life.” -William Castle, The Tingler

“I’m William Castle, the director of the film you’re about to see. I feel obligated to warn you that some of the sensations, some of the physical reactions which the actors on the screen will feel, will also be experienced, for the first time in motion picture history, by certain members of this audience. I say ‘certain members’ because some people are more sensitive to these mysterious electronic impulses than others. These unfortunate, sensitive people will at times feel a strange tingling sensation. Others will feel it less strongly. But don’t be alarmed: you can protect yourself. At any time you are conscious of a tingling sensation, you can obtain immediate relief by screaming. Don’t be embarrassed to open your mouth and let it rip with all you’ve got, because the person in the seat right next to you will probably be screaming too. And remember this: a scream at the right time may save your life.” -William Castle, The Tingler

What I love the most about William Castle’s The House on Haunted Hill (1959) is that it’s a carnival funhouse brought to celluloid, replete with ghosts popping out of swinging doors and a skeleton bouncing on a string. His follow-up, The Tingler, is more notorious but perhaps viewed less often these days; given the lengths to which Castle made the film the ultimate theatrical horror experience, seeing The Tingler on television or on DVD is inescapably a watered-down experience: the equivalent of seeing a 3-D film in 2-D, with all the House of Wax yo-yo thrusts toward the camera seeming a tad more ridiculous than they otherwise might.

With The Tingler, William Castle became the king of the gimmick B-movie, as well as the ultimate showman. His previous picture had grossed a fortune, in no small part to its skeleton, which manifested itself inside the theater concurrent with the skeleton appearing at the climax of the film. To top this, he decided that his new film would be all gimmick – and proudly so. The entire premise of the film would be an elaborate excuse to push the audience into screaming like idiots. As scientist Vincent Price explains to us:

With The Tingler, William Castle became the king of the gimmick B-movie, as well as the ultimate showman. His previous picture had grossed a fortune, in no small part to its skeleton, which manifested itself inside the theater concurrent with the skeleton appearing at the climax of the film. To top this, he decided that his new film would be all gimmick – and proudly so. The entire premise of the film would be an elaborate excuse to push the audience into screaming like idiots. As scientist Vincent Price explains to us:

(1) When we become deathly afraid, a creature appears on our spinal column – a slug-like appendage which Price has dubbed “The Tingler.” (His assistant, played by Darryl Hickman, says, “The Tingler. Why not? Since we don’t know what it is yet, we can’t give it at Latin name.”)

(1) When we become deathly afraid, a creature appears on our spinal column – a slug-like appendage which Price has dubbed “The Tingler.” (His assistant, played by Darryl Hickman, says, “The Tingler. Why not? Since we don’t know what it is yet, we can’t give it at Latin name.”)

(2) The creature is strong enough to snap your spine. However, if you scream, you can make it disappear.

(3) Therefore, if you fail to scream, you may possibly die.

The whole reason this film exists is to arrive at point #3, a point which is directed at the audience watching The Tingler. It’s demonstrated when we see a deaf-mute woman (Judith Evelyn) frightened to death – killed by the Tingler because she cannot scream. Her death scene – later revealed to be orchestrated by her husband – is vintage Castle: she is woken at night when the window shuts on its own accord, and an empty rocking chair begins to rock. A one-armed man in a grotesque mask, wielding a machete, suddenly springs out of her husband’s bed and begins stalking her.

She runs into the hallway, where she’s threatened by a hairy arm with an axe. Taking refuge in the bathroom, she discovers the water in the sink flows with red blood – as red as the blood filling the bathtub, out of which emerges a groping hand. Castle innovatively mixes color with black-and-white footage in these striking images. If that weren’t the topper, then it’s the medicine cabinet swinging open, revealing her own death certificate, which states, “Cause of death: FRIGHT!”

She runs into the hallway, where she’s threatened by a hairy arm with an axe. Taking refuge in the bathroom, she discovers the water in the sink flows with red blood – as red as the blood filling the bathtub, out of which emerges a groping hand. Castle innovatively mixes color with black-and-white footage in these striking images. If that weren’t the topper, then it’s the medicine cabinet swinging open, revealing her own death certificate, which states, “Cause of death: FRIGHT!”

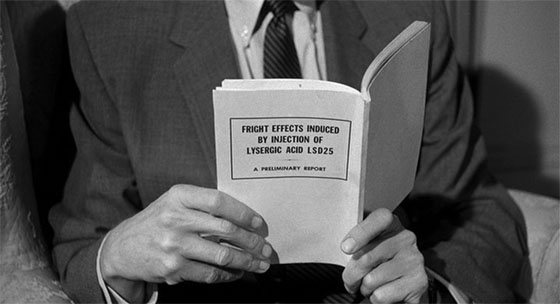

The premise of the film is both clever and ludicrous, as though inspired by an acid trip. Which makes sense, actually, since Price’s character experiments with LSD as part of his researches into fear, and subsequently partakes in cinema’s first acid freakout, screaming about walls closing in on him (while doing a bit of Marcel Marceau mime) before collapsing on his desk. From the late 50’s onward, Price had a long stretch of working in films that were beneath him – and subsequently elevating the material. But, to put this in Ed Wood terms, he seldom crawled into the pond with the octopus. In this memorable scene, he’s in the pond:

The premise of the film is both clever and ludicrous, as though inspired by an acid trip. Which makes sense, actually, since Price’s character experiments with LSD as part of his researches into fear, and subsequently partakes in cinema’s first acid freakout, screaming about walls closing in on him (while doing a bit of Marcel Marceau mime) before collapsing on his desk. From the late 50’s onward, Price had a long stretch of working in films that were beneath him – and subsequently elevating the material. But, to put this in Ed Wood terms, he seldom crawled into the pond with the octopus. In this memorable scene, he’s in the pond:

Yet one can only admire that Price leapt in with both feet to give William Castle the kind of film he wanted. Price’s performances have a way of acknowledging the campiness of the material without so much as a wink at the audience. He is always sincere, always engaging, but somehow you’re aware that he’s having the most fun he can with patently ridiculous material. (Not that there aren’t some great Price horror films, such as The Last Man on Earth, House of Usher, The Masque of the Red Death, Theater of Blood, or the revelatory Witchfinder General. I’m a fan.) The problem he runs into with The Tingler is that his character is maddeningly ill-defined. In one sustained sequence he threatens his cheating wife (Patricia Cutts) with murder, just so she can pass out and he can capture some X-rays of her spinal column to prove the Tingler’s existence. And yet, after he finally manages to wrangle a live Tingler (which almost kills him), he quickly abandons years of research, declaring: “David, to break the laws of nature is a dangerous thing. We’ve not only broken laws, we’ve violated some basic principles. We had to, but now we’re going to stop…That the Tingler exists in every human being we now know. Look at that Tingler, Dave, it’s an ugly and dangerous thing. Ugly, because it’s the creation of man’s fear, which is ugly too; dangerous, because a frightened man is dangerous.” Price delivers this dialogue like it’s Shakespeare, but his change of heart, just because he hadn’t yet learned how to properly handle a deadly creature, is contrived to say the least.

As you might expect, it’s too late for Price to reverse direction; the Tingler gets loose. And, in Castle’s coup de grace, it escapes into a movie theater (appropriately, Judith Evelyn’s deaf-mute worked in a moviehouse that only shows silent films). We see the slug-like creature wriggling up the aisle and onto a woman’s leg. She screams, and it falls free. At one point, the Tingler reaches the projection booth. The film is pulled from the projector and we see the silhouette of the Tingler (looking like a cheap child’s toy) moving across the screen. Then the lights go out, and in pitch-blackness we hear Price’s voice, speaking now directly to the audience of the film:

As you might expect, it’s too late for Price to reverse direction; the Tingler gets loose. And, in Castle’s coup de grace, it escapes into a movie theater (appropriately, Judith Evelyn’s deaf-mute worked in a moviehouse that only shows silent films). We see the slug-like creature wriggling up the aisle and onto a woman’s leg. She screams, and it falls free. At one point, the Tingler reaches the projection booth. The film is pulled from the projector and we see the silhouette of the Tingler (looking like a cheap child’s toy) moving across the screen. Then the lights go out, and in pitch-blackness we hear Price’s voice, speaking now directly to the audience of the film:

“Ladies and gentlemen, please do not panic – but SCREAM! Scream for your lives! The Tingler is loose in this theater! If you don’t scream, it may kill you! Scream, scream! Keep screaming! Scream for your lives!”

As part of the advertised “Percepto!” experience, Castle had directed theater owners to attach a mechanical vibration device to select movie seats in the theater. At this point in the film, with Vincent Price urging the audience to not panic but to SCREAM, those seats would now vibrate and rattle, hopefully convincing the “unfortunate, sensitive” patrons that the Tingler was on their spines, with screaming the only safe release. He also had a plant in the audience who would scream and then faint, with a fake nurse running down the aisle to escort the poor soul safely out.

As part of the advertised “Percepto!” experience, Castle had directed theater owners to attach a mechanical vibration device to select movie seats in the theater. At this point in the film, with Vincent Price urging the audience to not panic but to SCREAM, those seats would now vibrate and rattle, hopefully convincing the “unfortunate, sensitive” patrons that the Tingler was on their spines, with screaming the only safe release. He also had a plant in the audience who would scream and then faint, with a fake nurse running down the aisle to escort the poor soul safely out.

By all reports, the effect worked gangbusters, and the theater would be filled with both screams and laughter. That the climax of the film was essentially an interactive experience, with the audience providing the climax, is a rare achievement. One can imagine that attending one of these screenings was an event, more unique than 3-D. Is The Tingler a great horror film? Certainly not – the direction is workmanlike, the screenplay reliably absurd. (My favorite absurdity being the moment when Darryl Hickman, Price’s assistant, pulls up in a car stating that he brought a dog. We don’t see a dog in the car, but as he steps toward the door to let it out, Price asks, “A dog, what for?” “You say get a cat, I get a cat, remember? You say get a dog, I get a dog.” “We don’t need him,” Price responds. “‘A’ for effort,” Hickman shrugs, walking away from the car and leaving the invisible dog behind. Presumably the poor dog is locked inside the car for the remainder of the film.) But Castle wasn’t after Citizen Kane. He was a showman and an entertainer. He wanted to show teenagers a great time on a Saturday night, and The Tingler, when seen in the right circumstances, surely delivered. As the second film of their brief, beloved partnership, Castle and Price crafted another eighty-minute spookshow ride. You can practically feel the bar dropping down over your lap while Castle personally delivers his (Alfred Hitchcock-like) introduction, and away you go, past the floating screaming faces and down the track. It’s silly and, even in diluted, home video form, tremendously fun.

By all reports, the effect worked gangbusters, and the theater would be filled with both screams and laughter. That the climax of the film was essentially an interactive experience, with the audience providing the climax, is a rare achievement. One can imagine that attending one of these screenings was an event, more unique than 3-D. Is The Tingler a great horror film? Certainly not – the direction is workmanlike, the screenplay reliably absurd. (My favorite absurdity being the moment when Darryl Hickman, Price’s assistant, pulls up in a car stating that he brought a dog. We don’t see a dog in the car, but as he steps toward the door to let it out, Price asks, “A dog, what for?” “You say get a cat, I get a cat, remember? You say get a dog, I get a dog.” “We don’t need him,” Price responds. “‘A’ for effort,” Hickman shrugs, walking away from the car and leaving the invisible dog behind. Presumably the poor dog is locked inside the car for the remainder of the film.) But Castle wasn’t after Citizen Kane. He was a showman and an entertainer. He wanted to show teenagers a great time on a Saturday night, and The Tingler, when seen in the right circumstances, surely delivered. As the second film of their brief, beloved partnership, Castle and Price crafted another eighty-minute spookshow ride. You can practically feel the bar dropping down over your lap while Castle personally delivers his (Alfred Hitchcock-like) introduction, and away you go, past the floating screaming faces and down the track. It’s silly and, even in diluted, home video form, tremendously fun.

The Tingler is available on a 5-DVD box set, The William Castle Film Collection, from Columbia Pictures. Alas, it doesn’t include The House on Haunted Hill (which is available on many public domain editions elsewhere), but it does feature his famous 13 Ghosts (1960), and such rarities as Zotz! (1962), Mr. Sardonicus (1961), and the Hammer Films collaboration, The Old Dark House (1962). I’ll check in here with more Castle reviews as I work my way through the set. You can purchase the box set (and help support this site) through Amazon at this link:

The Tingler is available on a 5-DVD box set, The William Castle Film Collection, from Columbia Pictures. Alas, it doesn’t include The House on Haunted Hill (which is available on many public domain editions elsewhere), but it does feature his famous 13 Ghosts (1960), and such rarities as Zotz! (1962), Mr. Sardonicus (1961), and the Hammer Films collaboration, The Old Dark House (1962). I’ll check in here with more Castle reviews as I work my way through the set. You can purchase the box set (and help support this site) through Amazon at this link: