He adored women. He feared them and he worshipped them. Having found success as a WWII war photographer, when the war ended he switched subjects, and began to seduce women with his camera – first with pin-ups and early Playboy centerfolds, and then as a movie director. From this obsession, a career was born. Throughout his cluttered and sweaty-palmed filmography, Russ Meyer expressed his hot and bothered relationship with women again and again, populating his stories with the same broad caricatures, ritualistically enacting tales of voyeurism, impotence, violence, and occasionally sex. He wasn’t particularly interested in anything below the waist. He titled his mammoth autobiography A Clean Breast – a failed attempt at a double-entendre. The Russ Meyer woman was top-heavy (“cantilevered,” he insisted, as if she were architecture), brassy, and always in complete control. In later years some feminists would defend the topsy-turvy Meyerverse, where women stamped men beneath their boots and died with the same mad glory as James Cagney in White Heat. Drag queens would imitate his characters; John Waters championed him. A young film critic named Roger Ebert wrote a screenplay for him – Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) – and doctored some others, pushing Russ Meyer’s aesthetic even further into the cartoonishly absurd. Ultimately Meyer drove that convertible right off the cliff (I submit: 1979’s indigestible Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens), but in his best films, he presented a vision of America that – accidentally or not – brilliantly parodied the country’s image of itself, where Marlboro Men and Playboy bunnies fought a battle of the sexes like Greek gods on the fields of Troy.

He adored women. He feared them and he worshipped them. Having found success as a WWII war photographer, when the war ended he switched subjects, and began to seduce women with his camera – first with pin-ups and early Playboy centerfolds, and then as a movie director. From this obsession, a career was born. Throughout his cluttered and sweaty-palmed filmography, Russ Meyer expressed his hot and bothered relationship with women again and again, populating his stories with the same broad caricatures, ritualistically enacting tales of voyeurism, impotence, violence, and occasionally sex. He wasn’t particularly interested in anything below the waist. He titled his mammoth autobiography A Clean Breast – a failed attempt at a double-entendre. The Russ Meyer woman was top-heavy (“cantilevered,” he insisted, as if she were architecture), brassy, and always in complete control. In later years some feminists would defend the topsy-turvy Meyerverse, where women stamped men beneath their boots and died with the same mad glory as James Cagney in White Heat. Drag queens would imitate his characters; John Waters championed him. A young film critic named Roger Ebert wrote a screenplay for him – Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970) – and doctored some others, pushing Russ Meyer’s aesthetic even further into the cartoonishly absurd. Ultimately Meyer drove that convertible right off the cliff (I submit: 1979’s indigestible Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens), but in his best films, he presented a vision of America that – accidentally or not – brilliantly parodied the country’s image of itself, where Marlboro Men and Playboy bunnies fought a battle of the sexes like Greek gods on the fields of Troy.

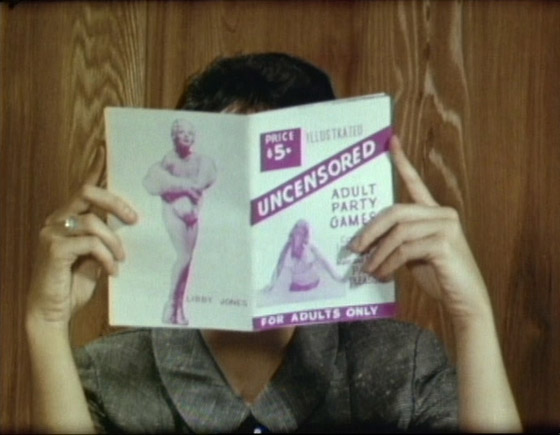

But years before he began to perfect his singular style, Meyer was still searching for a way to bring his pin-up aesthetic to celluloid. In the 1950’s, a filmgoer had limited means of catching a glimpse of naked flesh. Imported art films from overseas were beginning to push boundaries in this regard, of course, and there were occasional off-the-beaten path exploitation pictures, distributed as roadshows, which pushed the limits of violence and sex. In this latter category, some subgenres emerged, such as the “nudist” or “naturism” documentary, under the pretense of education, as well as films selling themselves as sex education or warnings on the dangers of sexually-transmitted diseases. These were deemed permissible, but they were all, of course, sexploitation to varying degress. When Russ Meyer picked up his movie camera, he invented a new kind of picture, the “nudie cutie.” Shedding any pretext of educational value, these were unabashedly leering, and proudly lacked any sort of moral value. Appropriately, his first fully-realized effort in this realm was called The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959).

But years before he began to perfect his singular style, Meyer was still searching for a way to bring his pin-up aesthetic to celluloid. In the 1950’s, a filmgoer had limited means of catching a glimpse of naked flesh. Imported art films from overseas were beginning to push boundaries in this regard, of course, and there were occasional off-the-beaten path exploitation pictures, distributed as roadshows, which pushed the limits of violence and sex. In this latter category, some subgenres emerged, such as the “nudist” or “naturism” documentary, under the pretense of education, as well as films selling themselves as sex education or warnings on the dangers of sexually-transmitted diseases. These were deemed permissible, but they were all, of course, sexploitation to varying degress. When Russ Meyer picked up his movie camera, he invented a new kind of picture, the “nudie cutie.” Shedding any pretext of educational value, these were unabashedly leering, and proudly lacked any sort of moral value. Appropriately, his first fully-realized effort in this realm was called The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959).

He asked his friend Bill Teas to star, naming the film after him as though he were a celebrity comic. Barely an hour long, it feels as though it were filmed on a lark over a weekend, which wasn’t far from the truth. Call it The Sexy Adventures of M. Hulot. Teas, playing himself as a lusting but repressed everyman, bumbles from one scene to the next with hardly a story to string him along: he goes to the dentist, has a drink at the bar, heads to the beach, and unloads his neuroses on an attractive psychiatrist. Reliably he encounters Meyer’s models, each triggering a daydream. He mentally undresses them, though his imagination has a curious way of delicately posing the women in the most un-pornographic way. The women might be unclothed, but they’re somehow demure. There’s no dialogue (no live sound was recorded), relying instead upon a narrator and an improvised zither and accordion score; the comedy relies heavily upon slow-burning visual gags.

He asked his friend Bill Teas to star, naming the film after him as though he were a celebrity comic. Barely an hour long, it feels as though it were filmed on a lark over a weekend, which wasn’t far from the truth. Call it The Sexy Adventures of M. Hulot. Teas, playing himself as a lusting but repressed everyman, bumbles from one scene to the next with hardly a story to string him along: he goes to the dentist, has a drink at the bar, heads to the beach, and unloads his neuroses on an attractive psychiatrist. Reliably he encounters Meyer’s models, each triggering a daydream. He mentally undresses them, though his imagination has a curious way of delicately posing the women in the most un-pornographic way. The women might be unclothed, but they’re somehow demure. There’s no dialogue (no live sound was recorded), relying instead upon a narrator and an improvised zither and accordion score; the comedy relies heavily upon slow-burning visual gags.

But Jacques Tati is not the influence here. Meyer loved burlesque shows and Li’l Abner cartoons, and the humor is lowbrow, cartoonish, and utterly harmless. The narration intentionally parodies that of the film’s “documentary” forebears, drily reading facts and statistics while nude women frolic. As a girl in her birthday suit heads down to the river with an inflatable raft, the narrator drones: “The outboard motor has brought a renewed interest in water sports in this country. Every year more and more marine enthusiasts flock to the shores of our lakes and streams for exercise and helpful relaxation.” As another woman soaps herself off in the water, and Teas watches from the bushes, we learn: “Advertisers have found that the women in America are keenly interested in the type of soap they use. In fact, the men of America have a keen interest in the product and how it is used also.” Meyer – who has a cameo as a cheering patron of a strip-club – is thumbing his nose at those who insist that these kinds of films contain socially redeeming value.

But Jacques Tati is not the influence here. Meyer loved burlesque shows and Li’l Abner cartoons, and the humor is lowbrow, cartoonish, and utterly harmless. The narration intentionally parodies that of the film’s “documentary” forebears, drily reading facts and statistics while nude women frolic. As a girl in her birthday suit heads down to the river with an inflatable raft, the narrator drones: “The outboard motor has brought a renewed interest in water sports in this country. Every year more and more marine enthusiasts flock to the shores of our lakes and streams for exercise and helpful relaxation.” As another woman soaps herself off in the water, and Teas watches from the bushes, we learn: “Advertisers have found that the women in America are keenly interested in the type of soap they use. In fact, the men of America have a keen interest in the product and how it is used also.” Meyer – who has a cameo as a cheering patron of a strip-club – is thumbing his nose at those who insist that these kinds of films contain socially redeeming value.

Surely the humor also helped to defuse the anxieties its audience might have had toward seeing this kind of film. It’s a comedy, and although its primary intent is clear, the jokes (lame as they are) allow for a communal theatrical experience. No need to feel isolated, over there in your raincoat. Everyone together can laugh, either with the film or at its expense. The sexual revolution lurked just over the horizon. Meyer was taking audiences by the hand: it’s just sex; lighten up.

Surely the humor also helped to defuse the anxieties its audience might have had toward seeing this kind of film. It’s a comedy, and although its primary intent is clear, the jokes (lame as they are) allow for a communal theatrical experience. No need to feel isolated, over there in your raincoat. Everyone together can laugh, either with the film or at its expense. The sexual revolution lurked just over the horizon. Meyer was taking audiences by the hand: it’s just sex; lighten up.

Not that he could disguise his own personal sexual obsession. Meyer was one of the great cinematic fetishists, as open in his adoration of breasts as Bunuel of legs, or Tarantino of bare feet. Teas is mesmerized by them; they have an hypnotic effect, leading to many of the film’s slapstick payoffs, such as they are. Meyer films the female chest as though capturing a rare and beautiful animal in the wild. His photographer’s talent is on display: in candy-colored footage, the women smile with red, red lips, displaying random props while they pose, looking as inviting as his pin-up work and drawing out the girl-next-door sensuality that made him such a favorite of Hugh Hefner’s.

Not that he could disguise his own personal sexual obsession. Meyer was one of the great cinematic fetishists, as open in his adoration of breasts as Bunuel of legs, or Tarantino of bare feet. Teas is mesmerized by them; they have an hypnotic effect, leading to many of the film’s slapstick payoffs, such as they are. Meyer films the female chest as though capturing a rare and beautiful animal in the wild. His photographer’s talent is on display: in candy-colored footage, the women smile with red, red lips, displaying random props while they pose, looking as inviting as his pin-up work and drawing out the girl-next-door sensuality that made him such a favorite of Hugh Hefner’s.

And yet, never has centerfold beauty seemed so deliriously stupid. In one prolonged sequence, Teas watches nude girls who lounge and play on the banks of a river, as though ready to declare, “Being naked is fun!” One sits and strums a guitar over her breasts; another just lies on her back as Meyer zooms in on her rouge lips and bright white teeth. He looks at girls the way a 13-year-old does: with awe. Any argument that Meyer objectifies women doesn’t hold against the adolescent innocence of it all. He doesn’t so much objectify women as sits back and beholds them.

And yet, never has centerfold beauty seemed so deliriously stupid. In one prolonged sequence, Teas watches nude girls who lounge and play on the banks of a river, as though ready to declare, “Being naked is fun!” One sits and strums a guitar over her breasts; another just lies on her back as Meyer zooms in on her rouge lips and bright white teeth. He looks at girls the way a 13-year-old does: with awe. Any argument that Meyer objectifies women doesn’t hold against the adolescent innocence of it all. He doesn’t so much objectify women as sits back and beholds them.

The Immoral Mr. Teas was an indie hit. Meyer had made a name for himself, and was given the financial support to make more movies. Eve and the Handyman (1961) is another entry in the now-gangbusters nudie cutie craze, and improves on Mr. Teas in subtle ways while essentially acting like a sequel. We’re introduced to a new protagonist (Anthony-James Ryan, more skilled at physical comedy than Bill Teas) who also klutzes through his daily routine while encountering beautiful women. But one woman keeps appearing, carefully studying his every movement, and disguising herself to infiltrate his mundane life.

The Immoral Mr. Teas was an indie hit. Meyer had made a name for himself, and was given the financial support to make more movies. Eve and the Handyman (1961) is another entry in the now-gangbusters nudie cutie craze, and improves on Mr. Teas in subtle ways while essentially acting like a sequel. We’re introduced to a new protagonist (Anthony-James Ryan, more skilled at physical comedy than Bill Teas) who also klutzes through his daily routine while encountering beautiful women. But one woman keeps appearing, carefully studying his every movement, and disguising herself to infiltrate his mundane life.

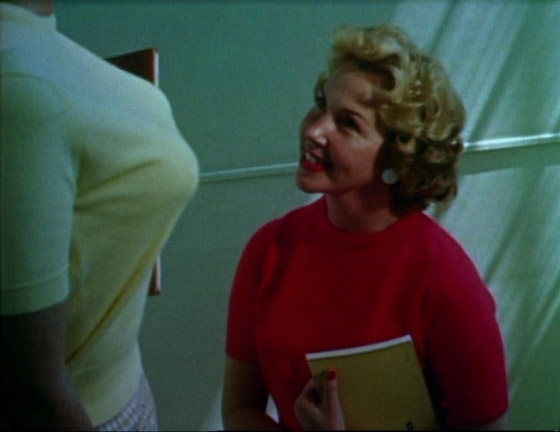

That woman is played by Eve Meyer, Russ’s pin-up model wife. Eve was a shrewd businesswoman and acted as producer of this film; she would go on to produce and help finance his films after their divorce, through the 60’s and into the early 70’s (tragically, she was killed in an infamous plane crash in the Canary Islands in 1977). Eve and the Handyman truly exists as a love letter to Eve Meyer. In a beret and trenchcoat, stalking her prey with a sultry frown or a wicked smile, Russ dares you to not be floored by his wife’s charms. And he wins; I submit. Eve reigns over the proceedings, and even, despite a brief striptease, never exposes so much as a nipple. Indeed, there’s surely less nudity in this film than in Mr. Teas. Yet Eve displays a cinematic charisma and a gift for the silent comedy Russ’s nudie cuties required, so she steals the picture handily.

That woman is played by Eve Meyer, Russ’s pin-up model wife. Eve was a shrewd businesswoman and acted as producer of this film; she would go on to produce and help finance his films after their divorce, through the 60’s and into the early 70’s (tragically, she was killed in an infamous plane crash in the Canary Islands in 1977). Eve and the Handyman truly exists as a love letter to Eve Meyer. In a beret and trenchcoat, stalking her prey with a sultry frown or a wicked smile, Russ dares you to not be floored by his wife’s charms. And he wins; I submit. Eve reigns over the proceedings, and even, despite a brief striptease, never exposes so much as a nipple. Indeed, there’s surely less nudity in this film than in Mr. Teas. Yet Eve displays a cinematic charisma and a gift for the silent comedy Russ’s nudie cuties required, so she steals the picture handily.

Granted, the film is essentially one very silly joke that takes an hour to arrive at its punchline. (The reason she’s following the handyman is revealed in a brief gag, and the film abruptly ends.) What makes this an improvement over its predecessor is not just Eve’s presence, but Russ’ blossoming skills as both director and editor. Although he can’t resist lingering close-ups of luscious cleavage, every shot has a comic strip’s sense of pop-art storytelling, with canted angles and bright primary colors. Meyer also has a natural rhythm for cutting, which begins to gain some musicality here, as Eve reads her soliloquies over Russ’s montages of San Francisco. He would take this style to almost avant-garde extremes by the end of the 60’s; fast cuts, dominated by breathless and absurdly florid narration, would be his calling card.

Granted, the film is essentially one very silly joke that takes an hour to arrive at its punchline. (The reason she’s following the handyman is revealed in a brief gag, and the film abruptly ends.) What makes this an improvement over its predecessor is not just Eve’s presence, but Russ’ blossoming skills as both director and editor. Although he can’t resist lingering close-ups of luscious cleavage, every shot has a comic strip’s sense of pop-art storytelling, with canted angles and bright primary colors. Meyer also has a natural rhythm for cutting, which begins to gain some musicality here, as Eve reads her soliloquies over Russ’s montages of San Francisco. He would take this style to almost avant-garde extremes by the end of the 60’s; fast cuts, dominated by breathless and absurdly florid narration, would be his calling card.

Of course, Meyer could still use a writer. Like Mr. Teas, Eve and the Handyman has its roots in burlesque, and so the comedy remains low even as the style rides high. But Meyer was always willing to experiment, and he was just getting started. He’d make a few more films in this genre, including the amazing Wild Gals of the Naked West (1962) – which is like a Benny Hill episode on LSD – but by 1964 (and Lorna) he began to sink his teeth into campy melodrama, launching the second phase of his career, and much more entertaining and rewarding films than these. The man proved he could shoot a picture; now he was off to the races – with Tura Satana, Haji, Charles Napier, Erica Gavin, Stuart Lancaster, and other assorted Supervixens and Motorpsychos.

Of course, Meyer could still use a writer. Like Mr. Teas, Eve and the Handyman has its roots in burlesque, and so the comedy remains low even as the style rides high. But Meyer was always willing to experiment, and he was just getting started. He’d make a few more films in this genre, including the amazing Wild Gals of the Naked West (1962) – which is like a Benny Hill episode on LSD – but by 1964 (and Lorna) he began to sink his teeth into campy melodrama, launching the second phase of his career, and much more entertaining and rewarding films than these. The man proved he could shoot a picture; now he was off to the races – with Tura Satana, Haji, Charles Napier, Erica Gavin, Stuart Lancaster, and other assorted Supervixens and Motorpsychos.