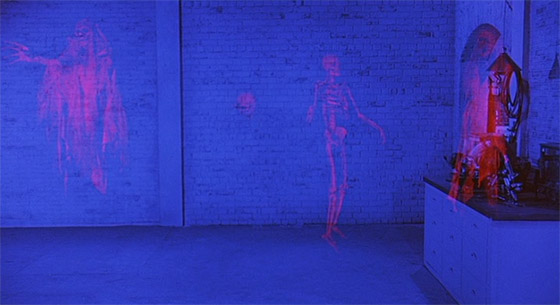

When I wrote about The Tingler (1959), I likened William Castle’s “gimmick” films to carnival spookshow rides. By that standard, 13 Ghosts (1960) is his version of Disney’s Haunted Mansion (which would open its doors in a few years). Each of the ghosts are introduced at the start of the film, swooping toward the camera in blood-red, so that you can identify them as characters before the ride itself begins. The chef! The flaming skeleton! The headless lion tamer and his roaring lion! After the beautifully blood-spattered credits, we switch back to black-and-white, and Castle himself appears to introduce another of his attractions – and to explain exactly how you need to experience it.

When I wrote about The Tingler (1959), I likened William Castle’s “gimmick” films to carnival spookshow rides. By that standard, 13 Ghosts (1960) is his version of Disney’s Haunted Mansion (which would open its doors in a few years). Each of the ghosts are introduced at the start of the film, swooping toward the camera in blood-red, so that you can identify them as characters before the ride itself begins. The chef! The flaming skeleton! The headless lion tamer and his roaring lion! After the beautifully blood-spattered credits, we switch back to black-and-white, and Castle himself appears to introduce another of his attractions – and to explain exactly how you need to experience it.

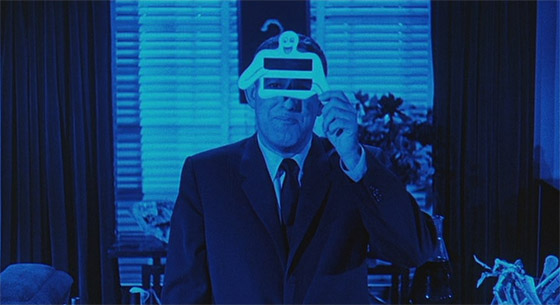

“Now when you came in, you were given a special Ghost Viewer, like this. And here’s how it works. Would you please change the color of the screen?” The film switches from black-and-white to blue. “Thank you. You must only use it when the screen changes to this kind of a bluish color. Then you raise the viewer to your eyes and you look at the screen through it. If you believe in ghosts, you look through the red part of the viewer. If you do not believe in ghosts, you look through the blue part…”

“Now when you came in, you were given a special Ghost Viewer, like this. And here’s how it works. Would you please change the color of the screen?” The film switches from black-and-white to blue. “Thank you. You must only use it when the screen changes to this kind of a bluish color. Then you raise the viewer to your eyes and you look at the screen through it. If you believe in ghosts, you look through the red part of the viewer. If you do not believe in ghosts, you look through the blue part…”

Thus is unveiled “Illusion-O.” Holding the cardboard visor, which is essentially a vertically-inclined version of red/blue 3-D glasses, the viewer can choose whether or not to see the red-colored ghosts which waver and flicker upon the deep-blue screen. But this is only for select sequences in the film, preceded by the subtitled words “USE VIEWER.” Since the characters in the film occasionally put on special glasses to see the ghosts, this is usually the moment when the audience needs to lift up their Ghost Viewers as well.

As schlock director Fred Olen Ray points out in the featurette accompanying the 13 Ghosts DVD, you didn’t even need to use the visor to see the ghosts – you’d be able to see them by just watching the film. (The only valid option the Ghost Viewer provided was to hide the ghosts, but why would you want to do that?) Still, Castle’s gimmick worked because it made the film another of his unique events, a one-of-a-kind experience that would fill up the seats. It would never replace 3-D, but it was fun.

As schlock director Fred Olen Ray points out in the featurette accompanying the 13 Ghosts DVD, you didn’t even need to use the visor to see the ghosts – you’d be able to see them by just watching the film. (The only valid option the Ghost Viewer provided was to hide the ghosts, but why would you want to do that?) Still, Castle’s gimmick worked because it made the film another of his unique events, a one-of-a-kind experience that would fill up the seats. It would never replace 3-D, but it was fun.

As a film, 13 Ghosts is slightly more competently made than most B-movies of the period, though not by much. It certainly has nothing on more straight-faced haunted house movies like The Uninvited (1944) or The Haunting (1963). A paleontologist with the improbable name of Cyrus Zorba (Donald Woods, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms) learns that his estranged uncle, one Dr. Plato Zorba, has recently died, leaving Cyrus’ family his entire mansion. The timing is fortuitous, since the Zorba household can no longer afford their bills, and have just had all their furniture repossessed. They hastily move into Dr. Zorba’s estate, which is still being tended by a housekeeper that their 10-year-old son Buck (Charles Herbert) calls a “witch.” Since she’s played by Margaret Hamilton, the Wicked Witch of the West herself, it’s an astute call.

As a film, 13 Ghosts is slightly more competently made than most B-movies of the period, though not by much. It certainly has nothing on more straight-faced haunted house movies like The Uninvited (1944) or The Haunting (1963). A paleontologist with the improbable name of Cyrus Zorba (Donald Woods, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms) learns that his estranged uncle, one Dr. Plato Zorba, has recently died, leaving Cyrus’ family his entire mansion. The timing is fortuitous, since the Zorba household can no longer afford their bills, and have just had all their furniture repossessed. They hastily move into Dr. Zorba’s estate, which is still being tended by a housekeeper that their 10-year-old son Buck (Charles Herbert) calls a “witch.” Since she’s played by Margaret Hamilton, the Wicked Witch of the West herself, it’s an astute call.

Dr. Zorba had been experimenting with capturing ghosts, and the family can hardly scoff when unexplained phenomena start occurring almost immediately. It’s sparked when their daughter, Medea (Jo Morrow, The 3 Worlds of Gulliver), discovers a Ouija board hidden in a secret compartment by the fireplace, and harmlessly suggests they gather round and use it. The Ouija board informs them that the house is haunted by 13 ghosts, and then implies very strongly that the ghosts want to kill Medea. How strongly? A painting almost collapses upon Medea’s head, then the Ouija planchette lifts up and places itself in her lap. “There’s probably a very simple explanation for [this],” Cyrus says helpfully, but soon he’s discovering Dr. Zorba’s secret laboratory, and putting on special glasses to see the ghosts for himself.

Dr. Zorba had been experimenting with capturing ghosts, and the family can hardly scoff when unexplained phenomena start occurring almost immediately. It’s sparked when their daughter, Medea (Jo Morrow, The 3 Worlds of Gulliver), discovers a Ouija board hidden in a secret compartment by the fireplace, and harmlessly suggests they gather round and use it. The Ouija board informs them that the house is haunted by 13 ghosts, and then implies very strongly that the ghosts want to kill Medea. How strongly? A painting almost collapses upon Medea’s head, then the Ouija planchette lifts up and places itself in her lap. “There’s probably a very simple explanation for [this],” Cyrus says helpfully, but soon he’s discovering Dr. Zorba’s secret laboratory, and putting on special glasses to see the ghosts for himself.

There’s a mystery of sorts in 13 Ghosts, a secret the house hides, a villain to be uncovered, a purpose the ghosts can serve. But it’s pretty rudimentary and predictable; the fun is in the haunted house thrills: the secret doors and passages, and scenes such as when young Buck casually explains the nature of the ghosts who lurk in the kitchen, and seems nonplussed even when a ghost hurtles a meat cleaver which misses his parents by a few inches. (The character of Buck, and the actor playing him, are somewhat reminiscent of Bill Mumy’s Will Robinson in Lost in Space.) Late in the film, there’s a séance scene which is one of the more memorable movie séances, and there’s a nifty, gloriously weird moment in which Buck explores the basement and encounters the lion and its headless tamer; the lion tamer saves Buck, and then goes searching for his missing head down the lion’s throat. None of it is terribly convincing. The spectral ghosts are sometimes effective, often ridiculous. Castle doesn’t do a very good job in hiding the strings that lift his “levitating” objects, nor the one guiding the fly that buzzes around Rosemary DeCamp’s head before getting zapped by the electric ghost-glasses.

There’s a mystery of sorts in 13 Ghosts, a secret the house hides, a villain to be uncovered, a purpose the ghosts can serve. But it’s pretty rudimentary and predictable; the fun is in the haunted house thrills: the secret doors and passages, and scenes such as when young Buck casually explains the nature of the ghosts who lurk in the kitchen, and seems nonplussed even when a ghost hurtles a meat cleaver which misses his parents by a few inches. (The character of Buck, and the actor playing him, are somewhat reminiscent of Bill Mumy’s Will Robinson in Lost in Space.) Late in the film, there’s a séance scene which is one of the more memorable movie séances, and there’s a nifty, gloriously weird moment in which Buck explores the basement and encounters the lion and its headless tamer; the lion tamer saves Buck, and then goes searching for his missing head down the lion’s throat. None of it is terribly convincing. The spectral ghosts are sometimes effective, often ridiculous. Castle doesn’t do a very good job in hiding the strings that lift his “levitating” objects, nor the one guiding the fly that buzzes around Rosemary DeCamp’s head before getting zapped by the electric ghost-glasses.

Margaret Hamilton gets a nice gag at the end of the film in which she tips her hat to her famous Wizard of Oz role, but for me the highlight is William Castle’s “just a moment before you leave” speech at the close: “If any of you are not yet convinced there really are ghosts, take the supernatural viewer home with you. And tonight, when you’re alone, and your room is in darkness, look through the red part of the viewer – if you dare!” This man was doing God’s work.