The difference is that it’s real. Every high speed spin-out, every flip, every crash. They really drive those cars over raised bridges, through billboards, backwards into rivers, off steep precipices, through fences and into trees and buildings. It would be so easy to fake now, to digitally erase the cables or to CG it entirely, but the audience would know. Just as you know, watching Dirty Mary Crazy Larry (1974), that this is risky, seat-of-your-pants, bona-fide.

The difference is that it’s real. Every high speed spin-out, every flip, every crash. They really drive those cars over raised bridges, through billboards, backwards into rivers, off steep precipices, through fences and into trees and buildings. It would be so easy to fake now, to digitally erase the cables or to CG it entirely, but the audience would know. Just as you know, watching Dirty Mary Crazy Larry (1974), that this is risky, seat-of-your-pants, bona-fide.

It was a low-budget Twentieth Century Fox drive-in movie (adapted from a novel called The Chase by Richard Unekis), and the studio surely had modest expectations. Peter Fonda was given the lead (“Larry”), an icon thanks to Easy Rider (1969) but not a major box office star; and some talent was imported from England: Susan George (Straw Dogs) was to play Mary, a free-spirited American girl; attached to direct was John Hough, who had just made The Legend of Hell House (1973), and was an unusual choice for an American action film. Everyone, including a team of drivers led by stunt coordinator Al Wyatt, attacked this little film like they had something to prove.

The plot is straightforward, uncomplicated by twists and turns, unless they take the shape of dusty California roads. What makes it special is the telling: there isn’t much exposition, but we join Larry and his partner Deke (Adam Roarke, The Losers) right before they enact the heist of a supermarket – we only realize what it is they’re doing just as they’re doing it. While Larry marches into the store manager’s office to ask for the money from the safe, Deke breaks into the manager’s home and holds his wife and child hostage. Hough enlisted his Hell House star Roddy McDowall for an uncredited cameo as the supermarket manager, and it’s ideal casting, since McDowall is the prince of manic worried looks and nervous energy. It’s fascinating to watch his acting style opposite Fonda’s in their brief scene together. In films like The Trip (1967), Spirits of the Dead (1968), and Easy Rider, Fonda was the hunky flower child; Dirty Mary marks a transition into a persona Fonda would wear through much of the 70’s, that of the cocky, laid-back good ol’ boy. He struts into McDowall’s office expecting his prey to comply with every word, but at the first sign of resistance, Fonda’s gum-chewing grin vanishes, he picks up a framed picture of the man’s family, looks at it significantly, and says, “Mind if I use your phone?” For an ostensibly fun action movie, there’s a weird, chilly undercurrent, particularly in these early scenes. We hardly know Deke, for example, but he seems at first frighteningly detached, and when he seizes McDowall’s nude wife in the shower, we fear for the woman. He impatiently assures her that rape is the furthest thing from his mind – he just wants to get the job done; and as the film progresses, we come to like Deke, and perhaps trust him considerably more than “Crazy” Larry, who, behind his Cheshire smile and Mad Hatter giggle, proves less capable of empathy.

But their characters play out on the open road, and express themselves through maneuvers and escapes across the sun-bleached California countryside. Unwillingly they pick up Mary Coombs, a young drifter that Larry slept with the night before and promptly abandoned. Stowing away in his getaway car, wearing jeans and a denim bikini top, she hides his keys from him just to get on his nerves. Larry doesn’t have time to get rid of her as he hurries to pick up Deke and tear out of San Francisco. We’re half an hour into the film and barely know a thing about Larry, Deke, or Mary, and in fact many significant character details are explained only much, much later. Instead, we get to know them through their personalities: Deke, intelligent and reserved; Larry, careless and a bit cold; Mary, taunting but easily wounded, abrasive and unpredictable. She sets the two against one another. They ditch her twice but are forced to scoop her up again. (Among Fonda’s many David Mamet-style lines is, most memorably, “Every bone in her crotch I’m gonna break.”) She couldn’t care less that they robbed a supermarket, and doesn’t ask for a share of the loot; like Larry, she gets her kicks from the adventure of it all.

But their characters play out on the open road, and express themselves through maneuvers and escapes across the sun-bleached California countryside. Unwillingly they pick up Mary Coombs, a young drifter that Larry slept with the night before and promptly abandoned. Stowing away in his getaway car, wearing jeans and a denim bikini top, she hides his keys from him just to get on his nerves. Larry doesn’t have time to get rid of her as he hurries to pick up Deke and tear out of San Francisco. We’re half an hour into the film and barely know a thing about Larry, Deke, or Mary, and in fact many significant character details are explained only much, much later. Instead, we get to know them through their personalities: Deke, intelligent and reserved; Larry, careless and a bit cold; Mary, taunting but easily wounded, abrasive and unpredictable. She sets the two against one another. They ditch her twice but are forced to scoop her up again. (Among Fonda’s many David Mamet-style lines is, most memorably, “Every bone in her crotch I’m gonna break.”) She couldn’t care less that they robbed a supermarket, and doesn’t ask for a share of the loot; like Larry, she gets her kicks from the adventure of it all.

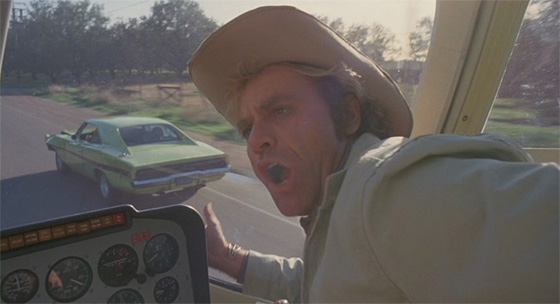

Every car chase movie requires a pursuer, a chief antagonist, and here it’s Vic Morrow playing Franklin, a police captain who refuses to wear a gun or a badge. He’s quite natural in the requisite, and labored, police station cutaways, as the film hammers home that he’s a tough-as-nails loose cannon, et cetera, et cetera. Once he gets off the CB and starts giving chase in a helicopter, Morrow is spectacular, ignoring his pilot’s warnings that they’re short on fuel, urging him to fly lower and lower until they’re swooping between rows of trees and ramming the roof of Fonda’s Dodge Charger.

Every car chase movie requires a pursuer, a chief antagonist, and here it’s Vic Morrow playing Franklin, a police captain who refuses to wear a gun or a badge. He’s quite natural in the requisite, and labored, police station cutaways, as the film hammers home that he’s a tough-as-nails loose cannon, et cetera, et cetera. Once he gets off the CB and starts giving chase in a helicopter, Morrow is spectacular, ignoring his pilot’s warnings that they’re short on fuel, urging him to fly lower and lower until they’re swooping between rows of trees and ramming the roof of Fonda’s Dodge Charger.

Watching this scene, as with so many of the film’s stunt sequences, is downright nerve-wracking. They really did fly a helicopter that close to the car, aiming its chopping blades mere feet from the Charger as it lunges forward, hovering above to rap its runners against the top of the car, gliding beside it so Morrow, in the helicopter, can be seen delivering his dialogue over the CB directly to Fonda, in the Charger. Hough and his stunt team were fearless. So were his actors. We frequently see Fonda at the wheel and George and Roarke beside him while he drives high-speed with the police in pursuit. We’re in the helicopter with Morrow, too, and it’s hard not to think that his life would end this way, tragically and pointlessly, when a helicopter and its spinning blades broke free above him and toppled, on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). There’s no connection, there’s no irony – but nevertheless it’s hard to free that thought from your mind. And still you have to admit to yourself that it’s thrilling to watch the actors and crew risk their lives to pull off these shots.

Watching this scene, as with so many of the film’s stunt sequences, is downright nerve-wracking. They really did fly a helicopter that close to the car, aiming its chopping blades mere feet from the Charger as it lunges forward, hovering above to rap its runners against the top of the car, gliding beside it so Morrow, in the helicopter, can be seen delivering his dialogue over the CB directly to Fonda, in the Charger. Hough and his stunt team were fearless. So were his actors. We frequently see Fonda at the wheel and George and Roarke beside him while he drives high-speed with the police in pursuit. We’re in the helicopter with Morrow, too, and it’s hard not to think that his life would end this way, tragically and pointlessly, when a helicopter and its spinning blades broke free above him and toppled, on the set of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). There’s no connection, there’s no irony – but nevertheless it’s hard to free that thought from your mind. And still you have to admit to yourself that it’s thrilling to watch the actors and crew risk their lives to pull off these shots.

Stuntwork aside, there’s an organic connection to how everything else in this film is shot. Hough rode in the car with his actors. Usually they didn’t rehearse their lines, and much of the dialogue is improvised. They were on the road, making a movie for all the hours that they had daylight, grabbing all the shots they could. The result is not just what you see but what you feel: that nothing is faked, that you’re on the trip and part of the getaway. Like Easy Rider, as well as the films to which it’s typically compared, Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and Vanishing Point (1971), you are on an authentic American road trip. That a British director could make such a quintessentially American film is an achievement; and though it ends on a cynical and downbeat (and utterly ridiculous) note, what you remember, and the reason you’ll go back to it, is that sense of liberation, of defying the speed limit and bearing for the hills; the way that Peter Fonda frets when he’s still and apart from the wheel, but grins whenever a police car appears in the rear-view mirror – with a sense of purpose.

Stuntwork aside, there’s an organic connection to how everything else in this film is shot. Hough rode in the car with his actors. Usually they didn’t rehearse their lines, and much of the dialogue is improvised. They were on the road, making a movie for all the hours that they had daylight, grabbing all the shots they could. The result is not just what you see but what you feel: that nothing is faked, that you’re on the trip and part of the getaway. Like Easy Rider, as well as the films to which it’s typically compared, Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and Vanishing Point (1971), you are on an authentic American road trip. That a British director could make such a quintessentially American film is an achievement; and though it ends on a cynical and downbeat (and utterly ridiculous) note, what you remember, and the reason you’ll go back to it, is that sense of liberation, of defying the speed limit and bearing for the hills; the way that Peter Fonda frets when he’s still and apart from the wheel, but grins whenever a police car appears in the rear-view mirror – with a sense of purpose.

The film grossed its budget fifteen times over, and Fonda, who was entitled to a certain percentage, became a wealthy man. It’s now available from Shout! Factory on a 2-DVD set with another Peter Fonda vehicle, Race with the Devil (1975). You can purchase it through Amazon here:

Dirty Mary Crazy Larry / Race With The Devil