In our journey through the cinema of William Castle, we are now, perhaps, reaching the point where our horror producer/director/showman extraordinaire might wish to consider giving up that whole “gimmick” thing which had been his cash-cow up until now. Because Mr. Sardonicus (1961) is an interesting film. I’d say that it doesn’t need a gimmick, upon which his previous films had relied so heavily. But the real problem here is that the gimmick is not integrated organically, as it was in The Tingler (1959) and 13 Ghosts (1960). Instead, like the same year’s Homicidal (1961), it springs at our faces like a jack-in-the-box at a point in the film that we’ve become lost in the story, and don’t want to be reminded that it’s “just a movie” – just another William Castle put-on. Mr. Sardonicus, before it goes off the rails, has promise.

In our journey through the cinema of William Castle, we are now, perhaps, reaching the point where our horror producer/director/showman extraordinaire might wish to consider giving up that whole “gimmick” thing which had been his cash-cow up until now. Because Mr. Sardonicus (1961) is an interesting film. I’d say that it doesn’t need a gimmick, upon which his previous films had relied so heavily. But the real problem here is that the gimmick is not integrated organically, as it was in The Tingler (1959) and 13 Ghosts (1960). Instead, like the same year’s Homicidal (1961), it springs at our faces like a jack-in-the-box at a point in the film that we’ve become lost in the story, and don’t want to be reminded that it’s “just a movie” – just another William Castle put-on. Mr. Sardonicus, before it goes off the rails, has promise.

Ray Russell adapted his own short story, “Sardonicus,” which had just been published in Playboy. The difference between the film and its source largely comes down to padding: it probably wouldn’t take 90 minutes to read “Sardonicus,” so Russell largely adds scenes of torture and sadism, presumably at Castle’s request, along with some repetitive dialogue and slow reveals of information that the audience had probably figured out much earlier. In other words, it could be shorter, and the source material is better, but couldn’t you say that about most films? Ronald Lewis (Scream of Fear) plays a young doctor, Robert Cargrave, whose work on patients suffering from various versions of paralysis has led to modest fame and a knighthood. As soon as he receives a written invitation from his former – and unrequited – flame (Audrey Dalton of 1953’s Titanic), now going by the title of Baroness Maude Sardonicus, he drops everything and heads to the dark and sinister castle where she now lives with her mysterious husband, the Baron (Guy Rolfe of Yesterday’s Enemy). How mysterious is the Baron? So mysterious he wears a lifelike mask to hide his features: a mask that slightly resembles William Castle, oddly enough.

Ray Russell adapted his own short story, “Sardonicus,” which had just been published in Playboy. The difference between the film and its source largely comes down to padding: it probably wouldn’t take 90 minutes to read “Sardonicus,” so Russell largely adds scenes of torture and sadism, presumably at Castle’s request, along with some repetitive dialogue and slow reveals of information that the audience had probably figured out much earlier. In other words, it could be shorter, and the source material is better, but couldn’t you say that about most films? Ronald Lewis (Scream of Fear) plays a young doctor, Robert Cargrave, whose work on patients suffering from various versions of paralysis has led to modest fame and a knighthood. As soon as he receives a written invitation from his former – and unrequited – flame (Audrey Dalton of 1953’s Titanic), now going by the title of Baroness Maude Sardonicus, he drops everything and heads to the dark and sinister castle where she now lives with her mysterious husband, the Baron (Guy Rolfe of Yesterday’s Enemy). How mysterious is the Baron? So mysterious he wears a lifelike mask to hide his features: a mask that slightly resembles William Castle, oddly enough.

Sir Robert knows something strange is up as soon as he enters the castle: following a woman’s screams, and ignoring the protestations of the one-eyed servant, he discovers that the maid has been tied up and covered in leeches. After liberating the maid, and receiving some assurances from the Bela Lugosi-esque servant, Krull (Oskar Homolka), that her wounds will be cared for, he shortly meets his beloved, as well as her tyrannical husband, so desperate to seek treatment for his hidden ailment that he resorts to routinely experimenting upon his staff. Sir Robert at last persuades Sardonicus to remove his mask, revealing a face pulled into a ghastly rictus grin (a la The Man Who Laughs; or Batman‘s Joker). Sardonicus tells his tale of woe: many years ago, his father died, but it was discovered only after he was buried that he took a winning lottery ticket with him. It was Sardonicus who elected to dig up his father’s corpse to recover the ticket on his person, but he was so struck with horror at the man’s partially-decomposed face, the mouth a rigor-mortis grin, that his own features were altered in a kind of psychosomatic reaction – mirroring the death-smile of the corpse. Now Sardonicus needs Sir Robert to accomplish what no other physician has been able to do: restore his face to its former handsomeness.

Sir Robert knows something strange is up as soon as he enters the castle: following a woman’s screams, and ignoring the protestations of the one-eyed servant, he discovers that the maid has been tied up and covered in leeches. After liberating the maid, and receiving some assurances from the Bela Lugosi-esque servant, Krull (Oskar Homolka), that her wounds will be cared for, he shortly meets his beloved, as well as her tyrannical husband, so desperate to seek treatment for his hidden ailment that he resorts to routinely experimenting upon his staff. Sir Robert at last persuades Sardonicus to remove his mask, revealing a face pulled into a ghastly rictus grin (a la The Man Who Laughs; or Batman‘s Joker). Sardonicus tells his tale of woe: many years ago, his father died, but it was discovered only after he was buried that he took a winning lottery ticket with him. It was Sardonicus who elected to dig up his father’s corpse to recover the ticket on his person, but he was so struck with horror at the man’s partially-decomposed face, the mouth a rigor-mortis grin, that his own features were altered in a kind of psychosomatic reaction – mirroring the death-smile of the corpse. Now Sardonicus needs Sir Robert to accomplish what no other physician has been able to do: restore his face to its former handsomeness.

Sir Robert takes sympathy at first (apparently forgetting all about the maid with the leeches), and agrees to begin treatment immediately, but very soon finds that the facial muscles of Sardonicus are too rigid to manipulate. Yet Baron Sardonicus will not accept “no, you crazed sadist” for an answer. He threatens to torture and rape Maude, who had up until now been “wife” in name only – so Robert complies with the only treatment that could possibly work on someone as psychologically disturbed as Sardonicus. Again, this is all faithful to Russell’s story, but expanded; the most significant change is that Sardonicus wears a mask to hide his appearance, and has taught himself to ventriloquize past his clamped teeth and parted lips, so he can annunciate his m‘s and b‘s, and speak with Guy Rolfe’s impeccable diction.

Sir Robert takes sympathy at first (apparently forgetting all about the maid with the leeches), and agrees to begin treatment immediately, but very soon finds that the facial muscles of Sardonicus are too rigid to manipulate. Yet Baron Sardonicus will not accept “no, you crazed sadist” for an answer. He threatens to torture and rape Maude, who had up until now been “wife” in name only – so Robert complies with the only treatment that could possibly work on someone as psychologically disturbed as Sardonicus. Again, this is all faithful to Russell’s story, but expanded; the most significant change is that Sardonicus wears a mask to hide his appearance, and has taught himself to ventriloquize past his clamped teeth and parted lips, so he can annunciate his m‘s and b‘s, and speak with Guy Rolfe’s impeccable diction.

William Castle’s idea of period (19th century) horror seems rooted in 30’s and 40’s Universal Studios monster movies. Fog permeates every outdoor set, conveniently hiding the studio’s limitations, and the castle interiors are crawling with Expressionistic shadows. (The most Expressionistic touch is Sardonicus’s castle, which resembles a grinning skull.) Accents vary wildly in quality, but Ronald Lewis is quite good in the central role, and Rolfe, presumably cast because of his Basil Rathbone qualities, creates a chilling personality that the mask can’t hide. Despite the fact that he casually tortures his maid (she’s strung up by her thumbs at one point), his creepiest moment comes when he surveys a group of village girls that Krull has gathered. The girls thought they were being offered money to attend a party; instead, Sardonicus is seeking a sexual partner in the absence of his wife’s affections. He looks them over like slaves on an auction block. You wouldn’t see this in a Karloff/Lugosi film.

William Castle’s idea of period (19th century) horror seems rooted in 30’s and 40’s Universal Studios monster movies. Fog permeates every outdoor set, conveniently hiding the studio’s limitations, and the castle interiors are crawling with Expressionistic shadows. (The most Expressionistic touch is Sardonicus’s castle, which resembles a grinning skull.) Accents vary wildly in quality, but Ronald Lewis is quite good in the central role, and Rolfe, presumably cast because of his Basil Rathbone qualities, creates a chilling personality that the mask can’t hide. Despite the fact that he casually tortures his maid (she’s strung up by her thumbs at one point), his creepiest moment comes when he surveys a group of village girls that Krull has gathered. The girls thought they were being offered money to attend a party; instead, Sardonicus is seeking a sexual partner in the absence of his wife’s affections. He looks them over like slaves on an auction block. You wouldn’t see this in a Karloff/Lugosi film.

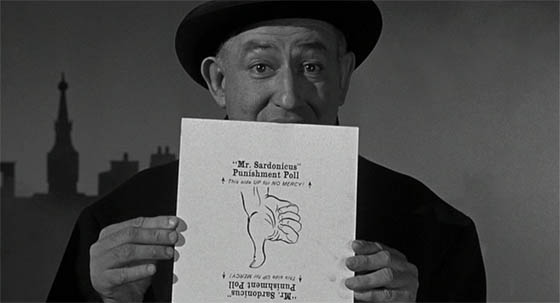

All these edgy, “modern” horror touches – sex and sadism – serve Castle only to a point, because he cannot resist, two minutes from the end of the picture, interrupting the story to address us directly. It’s time for the “Punishment Poll.” Each audience member was handed a small sign depicting a hand aiming a thumb. Castle asks the crowd to hold their cards out facing the screen – so he can read them – and give a thumb’s-up if Sardonicus doesn’t deserve punishment, or a thumb’s-down if he should “suffer, suffer, suffer.” Castle leans toward the camera, squinting, and pretends to take count of all thumbs in the audience. The conclusion to this exercise shouldn’t surprise you. The audience has voted to punish Sardonicus – I mean, come on, leeches on maids! – and so we witness the Baron’s come-uppance. There was never a happy ending filmed for Mr. Sardonicus, and of course the audience knew what the poll result would inevitably be. They were playing along. Castle always promised a good time, and audiences expected this sort of thing by now. But the adult and disturbing tone of what played in the last eighty or so minutes does not call for Castle’s final cameo, and another audience-participation game. With Homicidal, he had begun to make his films more adult. Mr. Sardonicus suggests that perhaps it was time to leave those kids at home.

All these edgy, “modern” horror touches – sex and sadism – serve Castle only to a point, because he cannot resist, two minutes from the end of the picture, interrupting the story to address us directly. It’s time for the “Punishment Poll.” Each audience member was handed a small sign depicting a hand aiming a thumb. Castle asks the crowd to hold their cards out facing the screen – so he can read them – and give a thumb’s-up if Sardonicus doesn’t deserve punishment, or a thumb’s-down if he should “suffer, suffer, suffer.” Castle leans toward the camera, squinting, and pretends to take count of all thumbs in the audience. The conclusion to this exercise shouldn’t surprise you. The audience has voted to punish Sardonicus – I mean, come on, leeches on maids! – and so we witness the Baron’s come-uppance. There was never a happy ending filmed for Mr. Sardonicus, and of course the audience knew what the poll result would inevitably be. They were playing along. Castle always promised a good time, and audiences expected this sort of thing by now. But the adult and disturbing tone of what played in the last eighty or so minutes does not call for Castle’s final cameo, and another audience-participation game. With Homicidal, he had begun to make his films more adult. Mr. Sardonicus suggests that perhaps it was time to leave those kids at home.