The very first images in Demons of the Mind (1972) are of imprisonment. A slender female hand slips through the bars of a carriage window, groping toward the open air – and then is pulled back by a dark-gloved hand. Elizabeth Zorn (Gillian Hills) retreats into her seat beside stern Aunt Hilda (Yvonne Mitchell). She remembers her brief freedom – how she met a young student in the woods, Carl Richter (Paul Jones), and fell in love. But now she is carried back to the family estate, where her father, the Baron (Robert Hardy), ensures that she and her brother Emil (Shane Briant) are kept under lock and key, and subjected to cruel treatments for what the Baron insists is a disease of the blood, carried down through his own bloodline, which causes homicidal madness.

The very first images in Demons of the Mind (1972) are of imprisonment. A slender female hand slips through the bars of a carriage window, groping toward the open air – and then is pulled back by a dark-gloved hand. Elizabeth Zorn (Gillian Hills) retreats into her seat beside stern Aunt Hilda (Yvonne Mitchell). She remembers her brief freedom – how she met a young student in the woods, Carl Richter (Paul Jones), and fell in love. But now she is carried back to the family estate, where her father, the Baron (Robert Hardy), ensures that she and her brother Emil (Shane Briant) are kept under lock and key, and subjected to cruel treatments for what the Baron insists is a disease of the blood, carried down through his own bloodline, which causes homicidal madness.

For a while, we see no evidence at all of this madness. It appears that the Baron is projecting his own neuroses onto his two children, and their sickly pallor is surely maintained by the bleeding each of them is forced to endure at the hands of Aunt Hilda. (The sadistic devices for this purpose, including a small mechanical box that slices efficiently through the skin, are actual medical instruments.) But soon enough we learn that young women are being killed in the small village outside the Zorn estate: strangled and decorated with rose petals. Are the murders being caused by the Zorn children? Or is it the Baron himself, who increasingly acts erratically, and submits to a psychoanalysis-via-hypnotism at the hands of Dr. Falkenberg (Patrick Magee, giving a nervous and twitchy performance)? Through this method we learn that years ago he married a peasant woman, who went mad and sliced open her wrist and throat before the children, effectively traumatizing them. There’s a lot of psychological baggage to unpack here, more so than the average Hammer film; but I haven’t even mentioned the ranting priest (Michael Hordern) who wanders into town one day in the middle of a downpour, and taps into the mob mentality that lies behind the town’s curious Wicker Man-style ritual called “Carrying Out Death,” which is considered harmless by the villagers, but has all the trappings of a lynching. (“We carry death to the fires of Hell! All is well! All is well!”)

For a while, we see no evidence at all of this madness. It appears that the Baron is projecting his own neuroses onto his two children, and their sickly pallor is surely maintained by the bleeding each of them is forced to endure at the hands of Aunt Hilda. (The sadistic devices for this purpose, including a small mechanical box that slices efficiently through the skin, are actual medical instruments.) But soon enough we learn that young women are being killed in the small village outside the Zorn estate: strangled and decorated with rose petals. Are the murders being caused by the Zorn children? Or is it the Baron himself, who increasingly acts erratically, and submits to a psychoanalysis-via-hypnotism at the hands of Dr. Falkenberg (Patrick Magee, giving a nervous and twitchy performance)? Through this method we learn that years ago he married a peasant woman, who went mad and sliced open her wrist and throat before the children, effectively traumatizing them. There’s a lot of psychological baggage to unpack here, more so than the average Hammer film; but I haven’t even mentioned the ranting priest (Michael Hordern) who wanders into town one day in the middle of a downpour, and taps into the mob mentality that lies behind the town’s curious Wicker Man-style ritual called “Carrying Out Death,” which is considered harmless by the villagers, but has all the trappings of a lynching. (“We carry death to the fires of Hell! All is well! All is well!”)

Perhaps there are too many elements floating about; indeed, on a first viewing you’ll spend a great deal of time just trying to figure out what’s going on, but it all comes together, more or less, by the end. Demons of the Mind is most interesting for the modern viewer when seen in the context of late-period Hammer horror, when the studio was trying to figure out how it could adapt into the 1970’s – a struggle it ultimately lost. At Hammer, Michael Carreras was taking over as chief executive from his father, Sir James Carreras, but his role was sabotaged from the start, since Hammer no longer enjoyed long-term distribution deals with the major American movie studios. Budgets were slashed and an air of desperation hung over many of their films, as they upped the exploitation ante (i.e., nudity and gore), and made ill-advised decisions such as inserting instantly-dated pop songs into Lust for a Vampire (1971) and Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972). Hammer’s veneer of class began to fade, and one of their rare hits, On the Buses (1971), wasn’t even horror, but an adaptation of a British sitcom. It’s been stated many times that Hammer should have been making edgier and more sophisticated horror films like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) or The Exorcist (1973), but this ignores the fact that (a) their finances were severely limited, and (b) when they did take risks, few noticed. 1972 saw the release of two risky projects that barely resembled the Hammer horror of the past: Peter Collinson’s harrowing and disturbing Straight On Till Morning, and Demons of the Mind.

Perhaps there are too many elements floating about; indeed, on a first viewing you’ll spend a great deal of time just trying to figure out what’s going on, but it all comes together, more or less, by the end. Demons of the Mind is most interesting for the modern viewer when seen in the context of late-period Hammer horror, when the studio was trying to figure out how it could adapt into the 1970’s – a struggle it ultimately lost. At Hammer, Michael Carreras was taking over as chief executive from his father, Sir James Carreras, but his role was sabotaged from the start, since Hammer no longer enjoyed long-term distribution deals with the major American movie studios. Budgets were slashed and an air of desperation hung over many of their films, as they upped the exploitation ante (i.e., nudity and gore), and made ill-advised decisions such as inserting instantly-dated pop songs into Lust for a Vampire (1971) and Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972). Hammer’s veneer of class began to fade, and one of their rare hits, On the Buses (1971), wasn’t even horror, but an adaptation of a British sitcom. It’s been stated many times that Hammer should have been making edgier and more sophisticated horror films like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) or The Exorcist (1973), but this ignores the fact that (a) their finances were severely limited, and (b) when they did take risks, few noticed. 1972 saw the release of two risky projects that barely resembled the Hammer horror of the past: Peter Collinson’s harrowing and disturbing Straight On Till Morning, and Demons of the Mind.

Shane Briant was in both, groomed to be one of the new Hammer stars. He had the right look: a pallid handsomeness, slightly tattered and weary; he looks a bit like Iain Quarrier’s vampire in The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), and, appropriately, Briant would go on to play a vampire himself in Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1974). His multi-faceted performance in Straight on Till Morning is indelibly chilling, but he gets a meaty enough part here as Emil Zorn: bled almost dry by Aunt Hilda, he needs to be propped up, or to support himself against the wall, as he stumbles about the estate. He’s at once sympathetic and unnerving – he seems to have incestuous longings for his sister Elizabeth. We want him to be free of his domineering father, but at the same time we’re a bit hesitant as to what he might do if he were free.

Shane Briant was in both, groomed to be one of the new Hammer stars. He had the right look: a pallid handsomeness, slightly tattered and weary; he looks a bit like Iain Quarrier’s vampire in The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967), and, appropriately, Briant would go on to play a vampire himself in Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1974). His multi-faceted performance in Straight on Till Morning is indelibly chilling, but he gets a meaty enough part here as Emil Zorn: bled almost dry by Aunt Hilda, he needs to be propped up, or to support himself against the wall, as he stumbles about the estate. He’s at once sympathetic and unnerving – he seems to have incestuous longings for his sister Elizabeth. We want him to be free of his domineering father, but at the same time we’re a bit hesitant as to what he might do if he were free.

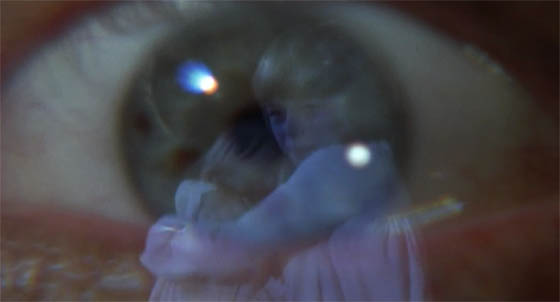

This is one of the rare starring roles for Gillian Hills, whose unusual career straddled the worlds of pop music and film. Prior to Demons of the Mind she’d starred in the camp classic Beat Girl (1960) as a wild teenager who defies her parents and strays into the world of strip clubs and beat music; her roles in two seminal films, Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), were small but scandalous. She led a double life in France, where as a teenager she starred in Roger Vadim’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1959), and recorded pop singles which are so bright, so ecstatic, that they remain among the strongest products of France’s so-called yé-yé girls. Listening to those amazing recordings, it’s difficult to believe that this girl in Demons of the Mind is the same person. Her presence is largely restrained to an empty, haunted stare, her full lips – typically turned to a fierce pout in Beat Girl – lie still and expressionless, only occasionally parting as though about to voice a longing which is taboo in the grounds of the Zorn house. Neither she nor her brother are permitted any passions. They are kept to their beds as prisoners.

This is one of the rare starring roles for Gillian Hills, whose unusual career straddled the worlds of pop music and film. Prior to Demons of the Mind she’d starred in the camp classic Beat Girl (1960) as a wild teenager who defies her parents and strays into the world of strip clubs and beat music; her roles in two seminal films, Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), were small but scandalous. She led a double life in France, where as a teenager she starred in Roger Vadim’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1959), and recorded pop singles which are so bright, so ecstatic, that they remain among the strongest products of France’s so-called yé-yé girls. Listening to those amazing recordings, it’s difficult to believe that this girl in Demons of the Mind is the same person. Her presence is largely restrained to an empty, haunted stare, her full lips – typically turned to a fierce pout in Beat Girl – lie still and expressionless, only occasionally parting as though about to voice a longing which is taboo in the grounds of the Zorn house. Neither she nor her brother are permitted any passions. They are kept to their beds as prisoners.

There’s a fairy tale quality to the film which can’t be understated. Elizabeth and Emil are Hansel and Gretel, with all the darker underpinnings of that tale brought gradually to the foreground. It’s telling that the film was originally going to be a werewolf story, but the werewolf was eventually excised, and the title Blood Will Have Blood gave way to the more overtly Freudian Demons of the Mind. Patrick Magee (who, like Hills, was in A Clockwork Orange) enters the story to split the psyche of the Zorn house wide open, like an exorcist taking on a haunted house, but he doesn’t resemble the Hammer characters typically played by Peter Cushing, Andrew Keir, or André Morell. He comes across as just as mentally unbalanced as his patients. This is a film about madness acting as a disease, and it spreads to nearly every character in the film, culminating in a crazed mob attack that is darker and more unsettling than those which would typically close a Frankenstein film. Hammer was experimenting here, and even though the experiment is not fully successful – for it lacks the compelling quality of, say, contemporary non-Hammer horrors like The Wicker Man (1973) or The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) – the fact that it chases its ideas so far out of Hammer’s comfort zone makes it worth a look.

There’s a fairy tale quality to the film which can’t be understated. Elizabeth and Emil are Hansel and Gretel, with all the darker underpinnings of that tale brought gradually to the foreground. It’s telling that the film was originally going to be a werewolf story, but the werewolf was eventually excised, and the title Blood Will Have Blood gave way to the more overtly Freudian Demons of the Mind. Patrick Magee (who, like Hills, was in A Clockwork Orange) enters the story to split the psyche of the Zorn house wide open, like an exorcist taking on a haunted house, but he doesn’t resemble the Hammer characters typically played by Peter Cushing, Andrew Keir, or André Morell. He comes across as just as mentally unbalanced as his patients. This is a film about madness acting as a disease, and it spreads to nearly every character in the film, culminating in a crazed mob attack that is darker and more unsettling than those which would typically close a Frankenstein film. Hammer was experimenting here, and even though the experiment is not fully successful – for it lacks the compelling quality of, say, contemporary non-Hammer horrors like The Wicker Man (1973) or The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) – the fact that it chases its ideas so far out of Hammer’s comfort zone makes it worth a look.