Last year, on a trip to Pennsylvania, I stopped by the Monroeville Mall (just outside Pittsburgh), where Dawn of the Dead (1978) was filmed. I’d nearly given up hope on finding anything George Romero-related when I discovered Monroeville Zombies, a gift shop and “zombie museum” commemorating the film, and the wonderfulness of zombies in general. The walls of the mini-museum were plastered with posters for zombie films, and I was amused to see included Night of the Comet, the 1984 sorta-zombie movie that I’d watched over and over again as an adolescent. I tried in vain to describe the awesomeness of Night of the Comet to my disinterested wife – or, rather, the awesomeness of my memories of the film, since I hadn’t seen it in many years. You see, there are these two teenage girls, and a comet wipes out almost all the inhabitants of the planet, so they go on a shopping spree at the mall! To Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun!” And they kill zombies, too! I’m sure my wife responded along the lines of, “Sounds great, dear.”

Last year, on a trip to Pennsylvania, I stopped by the Monroeville Mall (just outside Pittsburgh), where Dawn of the Dead (1978) was filmed. I’d nearly given up hope on finding anything George Romero-related when I discovered Monroeville Zombies, a gift shop and “zombie museum” commemorating the film, and the wonderfulness of zombies in general. The walls of the mini-museum were plastered with posters for zombie films, and I was amused to see included Night of the Comet, the 1984 sorta-zombie movie that I’d watched over and over again as an adolescent. I tried in vain to describe the awesomeness of Night of the Comet to my disinterested wife – or, rather, the awesomeness of my memories of the film, since I hadn’t seen it in many years. You see, there are these two teenage girls, and a comet wipes out almost all the inhabitants of the planet, so they go on a shopping spree at the mall! To Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun!” And they kill zombies, too! I’m sure my wife responded along the lines of, “Sounds great, dear.”

If Night of the Comet had been rated R, instead of PG-13, I wouldn’t have seen it at just the right age, when it acted as a post-apocalyptic wish-fulfillment fantasy. As you have probably guessed, I hadn’t seen the film’s chief inspiration, Dawn of the Dead, and wouldn’t for several more years (even then, I was always more of a Night of the Living Dead person; it wasn’t until my Monroeville Mall excursion that I rewatched the film, and truly came to appreciate Romero’s sequel). I was fascinated by the ideas in Night of the Comet, as well as the enticing genre soup writer/director Thom Eberhardt created: a bit of science fiction, a bit of horror, dollops of John Hughes-style teenage angst, a pinch of bleak end-of-the-world drama. Zombies, gun battles, shopping – hard to resist. Revisiting the film as an adult, I can add one more ingredient: 80’s-ness. It was hard to see just how 80’s this film was, back when I saw it…in the 80’s. We were all rather blind to it back then. But there is hardly a frame of this film which doesn’t scream the decade in which it was made, and that, undoubtedly, has only added to the film’s appeal. The nostalgia wafts thickly.

If Night of the Comet had been rated R, instead of PG-13, I wouldn’t have seen it at just the right age, when it acted as a post-apocalyptic wish-fulfillment fantasy. As you have probably guessed, I hadn’t seen the film’s chief inspiration, Dawn of the Dead, and wouldn’t for several more years (even then, I was always more of a Night of the Living Dead person; it wasn’t until my Monroeville Mall excursion that I rewatched the film, and truly came to appreciate Romero’s sequel). I was fascinated by the ideas in Night of the Comet, as well as the enticing genre soup writer/director Thom Eberhardt created: a bit of science fiction, a bit of horror, dollops of John Hughes-style teenage angst, a pinch of bleak end-of-the-world drama. Zombies, gun battles, shopping – hard to resist. Revisiting the film as an adult, I can add one more ingredient: 80’s-ness. It was hard to see just how 80’s this film was, back when I saw it…in the 80’s. We were all rather blind to it back then. But there is hardly a frame of this film which doesn’t scream the decade in which it was made, and that, undoubtedly, has only added to the film’s appeal. The nostalgia wafts thickly.

We meet two teenage sisters in Los Angeles: cinema usher Regina (Catherine Mary Stewart of The Last Starfighter) and cheerleader Samantha (Kelli Maroney of Chopping Mall). Regina’s the rebellious one; she’s sleeping with the projectionist, a film geek who prides his 3-D print of It Came From Outer Space, and during the work hours she wastes time in the theater lobby racking up high scores on Tempest. Samantha, for her part, is contentedly shallow. A comet is passing near Earth which hasn’t visited the planet since the dinosaurs mysteriously vanished – a clue dropped by the booming-voiced narrator who introduces the film and then promptly disappears for the remainder. Comet parties are being held across the globe, but Regina is using the opportunity of limited parental supervision to lock herself in the steel-encased projection booth with her boyfriend for the evening. That poster for the Jean Harlow film Red Dust that’s hanging on the wall is foreshadowing: when she wakes up the next morning, the comet has obliterated most Earthlings into little piles of…red dust. Those less directly exposed are beginning to decay, and their personalities turn homicidal. Regina decides that only the steel casing of the projection booth kept her and her boyfriend alive, since Samantha survived the evening by sleeping in a steel-walled shack. When a comet-altered man – let’s just call him a zombie, since the characters do – murders Regina’s boyfriend, they decide to hole up in a radio station. Here they meet Hector (Robert Beltran, Eating Raoul), a hunky truck driver who immediately hits it off with Regina. This leads Samantha to complain, “My sister, who’s swiped every guy I ever had my eye on, has now swiped the last guy on the whole freaked-out world.”

We meet two teenage sisters in Los Angeles: cinema usher Regina (Catherine Mary Stewart of The Last Starfighter) and cheerleader Samantha (Kelli Maroney of Chopping Mall). Regina’s the rebellious one; she’s sleeping with the projectionist, a film geek who prides his 3-D print of It Came From Outer Space, and during the work hours she wastes time in the theater lobby racking up high scores on Tempest. Samantha, for her part, is contentedly shallow. A comet is passing near Earth which hasn’t visited the planet since the dinosaurs mysteriously vanished – a clue dropped by the booming-voiced narrator who introduces the film and then promptly disappears for the remainder. Comet parties are being held across the globe, but Regina is using the opportunity of limited parental supervision to lock herself in the steel-encased projection booth with her boyfriend for the evening. That poster for the Jean Harlow film Red Dust that’s hanging on the wall is foreshadowing: when she wakes up the next morning, the comet has obliterated most Earthlings into little piles of…red dust. Those less directly exposed are beginning to decay, and their personalities turn homicidal. Regina decides that only the steel casing of the projection booth kept her and her boyfriend alive, since Samantha survived the evening by sleeping in a steel-walled shack. When a comet-altered man – let’s just call him a zombie, since the characters do – murders Regina’s boyfriend, they decide to hole up in a radio station. Here they meet Hector (Robert Beltran, Eating Raoul), a hunky truck driver who immediately hits it off with Regina. This leads Samantha to complain, “My sister, who’s swiped every guy I ever had my eye on, has now swiped the last guy on the whole freaked-out world.”

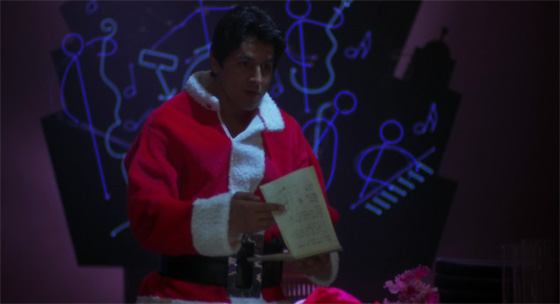

But we know they’re not alone, because periodically we check in with a group of scientists living in a military compound out in the desert, exposed to the comet’s effects and desperately trying to find a cure. So desperate, in fact, that they’ll use any survivors they find for fresh blood transfusions – including a pair of children. Meanwhile, Hector temporarily abandons the two sisters so he can check on his family, leading to a battle with a zombie adolescent in his home. Regina and Samantha work through their stress by shopping; thus the obligatory 80’s music montage, and the Cyndi Lauper. Their decadent mall experience is interrupted by some psychos in sunglasses (in Night of the Comet, never trust someone in sunglasses – they’re hiding their zombie eyes); Regina fires at the assailants with her submachine gun while Samantha throws shoes at them. They’re rescued by the scientists, but only for what promises to be a worse end; a sympathetic Mary Woronov (Death Race 2000) fakes Samantha’s death so she can be reunited with Hector (who returns to the radio station wearing a Santa Claus suit and beard), but Regina is brought back to the military facility to unwittingly supply the scientists with all the fresh blood they need. Hector and Samantha go to the rescue.

But we know they’re not alone, because periodically we check in with a group of scientists living in a military compound out in the desert, exposed to the comet’s effects and desperately trying to find a cure. So desperate, in fact, that they’ll use any survivors they find for fresh blood transfusions – including a pair of children. Meanwhile, Hector temporarily abandons the two sisters so he can check on his family, leading to a battle with a zombie adolescent in his home. Regina and Samantha work through their stress by shopping; thus the obligatory 80’s music montage, and the Cyndi Lauper. Their decadent mall experience is interrupted by some psychos in sunglasses (in Night of the Comet, never trust someone in sunglasses – they’re hiding their zombie eyes); Regina fires at the assailants with her submachine gun while Samantha throws shoes at them. They’re rescued by the scientists, but only for what promises to be a worse end; a sympathetic Mary Woronov (Death Race 2000) fakes Samantha’s death so she can be reunited with Hector (who returns to the radio station wearing a Santa Claus suit and beard), but Regina is brought back to the military facility to unwittingly supply the scientists with all the fresh blood they need. Hector and Samantha go to the rescue.

Given the fact that the plot boasts zombies, gunfights, and daring escapes, what’s most curious about Night of the Comet is its tone, which remains ridiculously mellow for its entire 90 minutes. That might be because most of the time is spent in the FM radio station, which is surely the mellowest place on Earth: dim lighting, flashing neon, and nonstop easy-listening music hosted by the ghost of a DJ (his voice runs off pre-recorded tapes, which doesn’t explain why he’s able to deliver weather updates). The station looks like the perfect place for a nap. Have you fallen asleep while trying to get through Night of the Comet on some afternoon TV screening? It’s that damn radio station. The characters, in fact, take naps themselves: Samantha dreams she’s assaulted by zombies, and we’re given a nightmare-within-a-nightmare sequence which is the film’s most effective jolt, even if it’s borrowed wholesale from An American Werewolf in London (1981).

Given the fact that the plot boasts zombies, gunfights, and daring escapes, what’s most curious about Night of the Comet is its tone, which remains ridiculously mellow for its entire 90 minutes. That might be because most of the time is spent in the FM radio station, which is surely the mellowest place on Earth: dim lighting, flashing neon, and nonstop easy-listening music hosted by the ghost of a DJ (his voice runs off pre-recorded tapes, which doesn’t explain why he’s able to deliver weather updates). The station looks like the perfect place for a nap. Have you fallen asleep while trying to get through Night of the Comet on some afternoon TV screening? It’s that damn radio station. The characters, in fact, take naps themselves: Samantha dreams she’s assaulted by zombies, and we’re given a nightmare-within-a-nightmare sequence which is the film’s most effective jolt, even if it’s borrowed wholesale from An American Werewolf in London (1981).

You can’t help but wish there were more scares in Night of the Comet, which introduces the promise of zombie attacks and then gradually forgets about the zombies, as the characters begin to deal with less-decayed, more human foes: first the chatty stockboy and his gang of thugs in the mall, then the cold-hearted scientists. Eberhardt seems less interested in action and horror than he is reveling in mood: the loneliness and boredom of characters lost in a suddenly vacated world. He’s also keen on his color schemes, in particular the color red; the dusky hues of the sky match the piles of dust that spot the streets and sidewalks. The smog-choked Los Angeles skyline provides the film’s cheapest and most effective special effect. It looks like a comet just passed and altered the atmosphere, because L.A. always looks like that.

You can’t help but wish there were more scares in Night of the Comet, which introduces the promise of zombie attacks and then gradually forgets about the zombies, as the characters begin to deal with less-decayed, more human foes: first the chatty stockboy and his gang of thugs in the mall, then the cold-hearted scientists. Eberhardt seems less interested in action and horror than he is reveling in mood: the loneliness and boredom of characters lost in a suddenly vacated world. He’s also keen on his color schemes, in particular the color red; the dusky hues of the sky match the piles of dust that spot the streets and sidewalks. The smog-choked Los Angeles skyline provides the film’s cheapest and most effective special effect. It looks like a comet just passed and altered the atmosphere, because L.A. always looks like that.

He also steals plenty of memorable shots of Catherine Mary Stewart and Kelli Maroney stalking the eerily deserted L.A. streets amid skyscrapers, which leads to Night of the Comet‘s very best gag, at the film’s end. Despite its languor and – mellowness – the film is a satire, and there are some nice jokes scattered throughout, such as Kelli’s obliviousness the morning after the comet’s passing (she wonders where her dog Muffy went, noticing a collar and a pile of red powder under it) – a bit more of this and we’d be in solid Shawn of the Dead territory. Maroney, who delivers the film’s funniest line (“Daddy would’ve gotten us Uzis”), sells the film’s concept by spending most of the movie in her cheerleader outfit: she’s the Omega Man as Valley Girl. But Eberhardt, who had previously directed the low-budget horror film Sole Survivor (1983), and would go on to direct comedies such as Without a Clue (1988), never hammers away too strongly at any of the elements he has at play. Night of the Comet is never as scary as it ought to be, never as funny as it ought to be, never as thrilling as it ought to be. It just kind of…is. But the concept and the images are so strong that the film sticks with you anyway, and by the end it proves itself to be strangely endearing. Indeed, that offbeat ending might just explain the film’s tonal oddity: it was headed here, of all places, and Night of the Comet earns the ending that it has. There are better post-apocalyptic films, but this one sticks with you, like an easy-listening FM song from the 80’s that you just can’t get out of your head. I’m going to go take a nap now.

He also steals plenty of memorable shots of Catherine Mary Stewart and Kelli Maroney stalking the eerily deserted L.A. streets amid skyscrapers, which leads to Night of the Comet‘s very best gag, at the film’s end. Despite its languor and – mellowness – the film is a satire, and there are some nice jokes scattered throughout, such as Kelli’s obliviousness the morning after the comet’s passing (she wonders where her dog Muffy went, noticing a collar and a pile of red powder under it) – a bit more of this and we’d be in solid Shawn of the Dead territory. Maroney, who delivers the film’s funniest line (“Daddy would’ve gotten us Uzis”), sells the film’s concept by spending most of the movie in her cheerleader outfit: she’s the Omega Man as Valley Girl. But Eberhardt, who had previously directed the low-budget horror film Sole Survivor (1983), and would go on to direct comedies such as Without a Clue (1988), never hammers away too strongly at any of the elements he has at play. Night of the Comet is never as scary as it ought to be, never as funny as it ought to be, never as thrilling as it ought to be. It just kind of…is. But the concept and the images are so strong that the film sticks with you anyway, and by the end it proves itself to be strangely endearing. Indeed, that offbeat ending might just explain the film’s tonal oddity: it was headed here, of all places, and Night of the Comet earns the ending that it has. There are better post-apocalyptic films, but this one sticks with you, like an easy-listening FM song from the 80’s that you just can’t get out of your head. I’m going to go take a nap now.