Walt Disney opened his Disneyland theme park on July 18, 1955, in Anaheim, California – just thirty-two miles from Hollywood. Disney had conquered cinema already, and now he had his sights set on a multi-media entertainment empire. In October of that year he premiered his television series on the ABC network, at first called Disneyland, in honor (and cross-promotion) of the park; it would later become Walt Disney Presents and, eventually, The Wonderful World of Disney. Through its various permutations, the anthology program would spotlight Disney animated shorts and films, made-for-TV movies, nature documentaries, behind-the-scenes specials on the Disney theme parks, Davy Crockett episodes and more. In the show’s earliest days, each week would present a theme program inspired by a particular section of Disneyland: Fantasyland, Frontierland, Adventureland, and, most intriguingly, Tomorrowland, which gave Disney the license to produce an hour of science-fact entertainment, and educate viewers on the solar system and the future of space exploration. These big-budget productions brought in Wernher von Braun as both a consultant and an on-screen personality.

Walt Disney opened his Disneyland theme park on July 18, 1955, in Anaheim, California – just thirty-two miles from Hollywood. Disney had conquered cinema already, and now he had his sights set on a multi-media entertainment empire. In October of that year he premiered his television series on the ABC network, at first called Disneyland, in honor (and cross-promotion) of the park; it would later become Walt Disney Presents and, eventually, The Wonderful World of Disney. Through its various permutations, the anthology program would spotlight Disney animated shorts and films, made-for-TV movies, nature documentaries, behind-the-scenes specials on the Disney theme parks, Davy Crockett episodes and more. In the show’s earliest days, each week would present a theme program inspired by a particular section of Disneyland: Fantasyland, Frontierland, Adventureland, and, most intriguingly, Tomorrowland, which gave Disney the license to produce an hour of science-fact entertainment, and educate viewers on the solar system and the future of space exploration. These big-budget productions brought in Wernher von Braun as both a consultant and an on-screen personality.

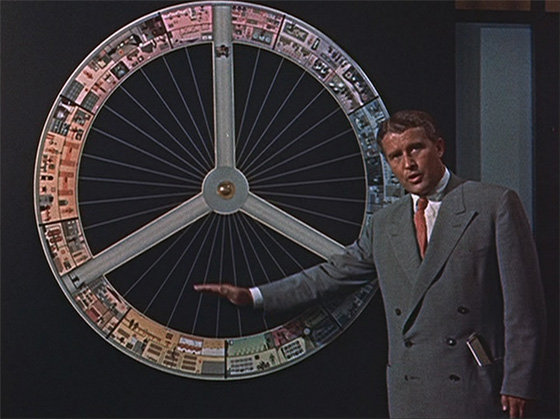

Wernher von Braun discusses a proposal for a space station with artificial gravity in "Man and the Moon"

Von Braun first came to America through the efforts of Harry Truman’s “Operation Paperclip,” enacted in the wake of WWII to acquire Germany’s talent before they were scooped up by other Allied powers. Paperclip was to recruit those German scientists and engineers who represented the country’s best and brightest, with the stated exclusion of members of the Nazi party. Some exceptions were made. The Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency falsified a biography for Nazi Germany’s eminent rocket scientist von Braun, and did the same for many others, to guarantee that the American military was receiving the cream of the crop regardless of their involvement with Hitler’s plans. It would not be part of von Braun’s record, for example, that he had been recruited by Himmler to join the SS, and that his work on the V-2 rocket was aided by slave labor picked out of concentration camps; it’s estimated that over 25,000 died by the brutal treatment in the industrial complexes at Mittelbau. (Von Braun later claimed that he had no choice but to join the SS, and to use the slave labor he was given, in order to continue his research.) In the United States, von Braun gradually rose to prominence as part of the American rocket program, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency, and his well-publicized idea that space travel was close to becoming reality was instrumental in launching the “space race.” He proposed detailed outlines for the construction of a space station and a voyage to Mars. When NASA was established in 1958, he joined as Director.

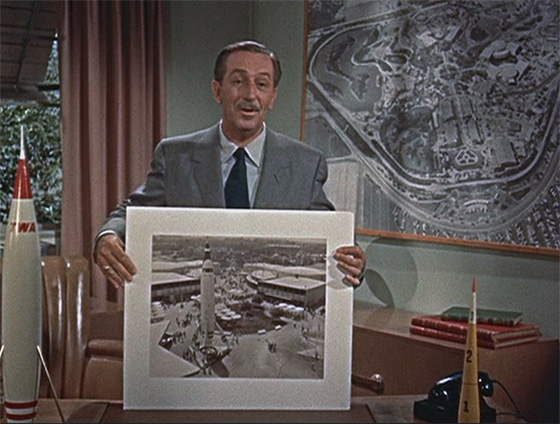

Walt Disney describes "Tomorrowland" in his introduction to "Man and the Moon"

Walt Disney was drawn to von Braun’s very big ideas. He saw a fellow dreamer, a futurist who wanted to see his vast, almost Utopian dreams accomplished within his own lifetime. Disney proposed three hour-long “Tomorrowland” television specials for his Disneyland series which would outline von Braun’s plans for space travel and then realize those concepts through animation and live-action science fiction sequences. He needed one more element, another dreamer with a prodigious imagination, someone capable of assembling his and von Braun’s ideas into tightly-constructed episodes of pure entertainment: that man was Ward Kimball. He was one of Disney’s reliable “Nine Old Men,” the animators who had overseen his classic animated films, and whose style and innovative techniques had immeasurably redefined the standards for cinematic animation. Kimball was the animator of Jiminy Crickett and some of the most memorable characters of 1951’s Alice in Wonderland (the Mad Hatter and the Cheshire Cat, Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee). He professed to know nothing about space or space travel, but was asked to write, direct, and produce all three of the Tomorrowland episodes Disney initially envisioned: these would be “Man in Space,” “Man and the Moon,” and “Mars and Beyond.” Kimball plunged into research with von Braun’s assistance, and emerged with three striking and unconventional hours of early television.

Animator Ward Kimball, director, producer, and co-writer of "Man and the Moon"

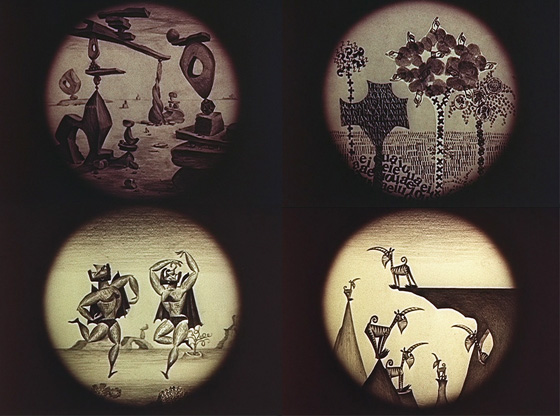

“Man and the Moon” debuted on December 28, 1955. After Walt Disney’s personalized and standard introduction, Ward Kimball himself arrives to present the program he and his team of researchers and animators have assembled. (He looks a bit like Elisha Cook Jr.) He leans forward into a microphone and announces, “Roll the moon sequence, please.” This first segment is the token Disney animated short, the highlight of each of the Tomorrowland programs. If you think of Disney’s shorts (with Mickey and company) as saccharine and toothless, Kimball’s work is a revelation: heavily stylized, constantly imaginative, filled with visual gags, puns, and artistic and literary references, and much more in line with Chuck Jones’ Looney Tunes for Warner Bros. At fifteen minutes, the animated film takes up a good chunk of the episode’s running time, but it holds your attention throughout, detailing the history of man’s fascination with the Moon, and its influence upon various cultures, through art, novels, proverbs, and song. As we’re told what “primitive man,” the Hindus, the Aegeans, the Egyptians, the Sumerians, the Greeks, and the Romans thought of the Moon, the animation style adapts as appropriate. We learn of the earliest science fiction stories portraying journeys to the Moon, and we’re told that in the Dark Ages, “for centuries the light of knowledge was extinguished, and only a fleeting mention of the Moon was made,” which Kimball illustrates by showing a black-cloaked soothsayer murmuring: “Moon.” Dark times indeed.

"The Dark Ages," as seen by Ward Kimball's animators

We see Johannes Kepler’s lunar fantasy novel Somnium reenacted, with Kepler kidnapped by “moon demons” and carried across the Moon’s shadow where he meets a one-eyed, spindly-legged moon creature. Only a few feet apart, they gaze at one another intently through telescopes. We see Cyrano de Bergerac attempt a journey to the Moon, but ending up in Canada, spouting random French phrases at the Indians (“Soupe du jour!” “Pepe le moko?” “Filet mignon!”). Romeo & Juliet and Othello opine about the Moon on the stage. Also illustrated is the “Great Moon Hoax,” the astronomer John Herschel’s reports of seeing lunar life through his telescope, and his visions are animated using Victorian-style (and Dali-esque) cut-outs that anticipate the animations of Terry Gilliam over a decade later.

Ward Kimball’s film ends with a song, “Ah! See the Moon,” which frantically recites Moon rhymes, and flips through animated scenes so quickly that it’s as though Kimball instructed his team to use up every single idea in their sketchbooks, squeezing them all into the last minutes of the short. Then our director returns in the flesh to explain the phases of the moon, the influence upon tides, and finally the landscape and geology of the Moon itself. It might be elementary, but it’s illustrated so neatly, using models and animation, that it would still be a useful teaching tool in a contemporary science class. From fact we move to speculation, and Wernher von Braun arrives to explain, with his thick German accent, how he believes space travel will be accomplished in the coming years. He describes how a trip to the Moon could be made possible by constructing a refueling station in space – a “space station,” if you will, which is shown as a large, wheel-shaped model, and a cut-away diagram of the structure’s interior which helpfully spins in rotation under his guiding hand. This spinning would accomplish an artificial gravity for the astronauts inside: a concept which Arthur C. Clarke would pursue time and again in his novels, most famously in his screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); Kubrick, who exhaustively researched his film, built something not dissimilar to von Braun’s plans full scale, to give the illusion of Keir Dullea running along the vertical circumference of a 360-degree track.

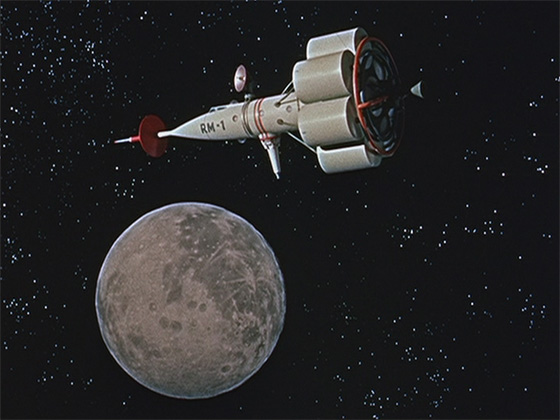

"Moonship RM-1" journeys to the Moon

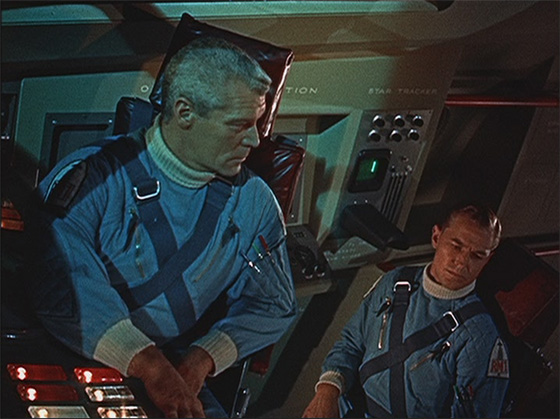

Following von Braun’s mini-lecture, the remainder of the hour is given over to a “science-factual” narrative, a cinematic equivalent to the Disneyland ride “Rocket to the Moon,” and founded upon the concepts which the rocket scientist just showed us. For this segment, Disney commissioned the construction of models of the Moon, the “R-M” rocketship, and the space station, plus interiors decorated with flashing buttons, levers, and consoles, with actors hired to wear suits and helmets that make them look not unlike Lego astronauts. When an astronaut travels from the “moonship” to the space station, his spacesuit is a multi-limbed pod which is best described as a flying ice cream cone: von Braun’s conception. They deal with a fuel leak in one of the rocket’s tanks, and (a bit tediously) deliver techno-babble while the musical score thunders on dramatically. Essentially it’s a small-screen version of films like Destination Moon, Rocketship X-M (1950), and Project Moon Base (1953), but with superior special effects, and certainly better research. Consider that all this expense was for one segment of one hour of television programming – with no DVD sales to fall back on to recoup the investment – and it’s doubly impressive. You can easily imagine that this would be terrifically compelling to audiences of 1955.

The RM-1 corrects its course to avoid a collision with the Moon.

The entire episode is leading to one moment which is pure 50’s SF nirvana. As the RM-1 travels to the “unknown side of the Moon,” aka the dark side, the ship is plunged into shadow and darkness. The captain shouts, “Okay, Frank! Fire your flares at three-minute intervals!” An animated flare arcs above the lunar surface, and the unexplored, heretofore unseen craters and seas are briefly exposed by a flash of light. Considering that we were still more than a decade away from reaching the Moon, these close-ups of the (model’s) surface look astonishingly close to real documentary footage. Then the ship’s crew discovers a high degree of radioactivity from one of the hidden areas; the “contour mapper” also reports some strange formations. The captain commands: “Get some flares in that area, quick!” Another animated flare is fired, and we see: what? A carved formation upon the rocks? A “Chariots of the Gods”-style message? A Selenite city? The viewers of 1955 only get a brief glimpse before the flare goes out; no option to rewind their Tivo.

Something is hidden on the dark side of the Moon.

As the rocketship prepares its homeward voyage, a narrator tells us the next goal is to uncover the mysteries of “The Red Planet Mars!” (An umbrella-shaped ship called the MARS 1 is shown drifting into the blackness of space.) This, in fact, would be the subject of the next “Tomorrowland” program, “Mars and Beyond.” We knew even less about Mars than we did the Moon back then, so Ward Kimball would be given a greater license to let his animators chase their imaginations to wild extremes. Von Braun was also game, and, judging by the stellar ratings, so was the American audience, who had been given a taste of optimism amidst the deep freeze of the Cold War…