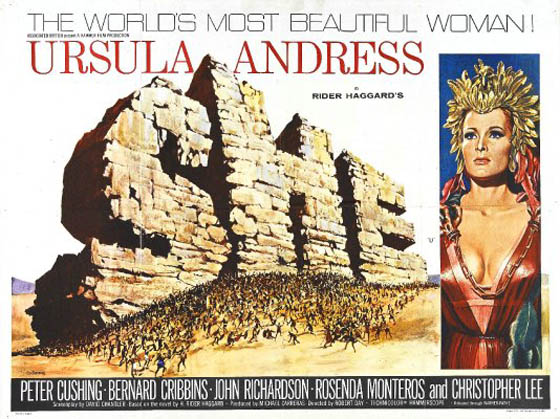

Hammer Films had grown steadily since the box office breakthroughs of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). Distributors knew that the British studio’s genre product was reliably classy and literate, but also sexy and violent; they certainly knew how to fill seats and please audiences. By the mid-60’s, Hammer producers Michael Carreras and Anthony Hinds were ready to swing for the fences: a Hollywood-style spectacle, with a bigger budget than the thrifty studio would typically allow. Hammer settled upon a known property, H. Rider Haggard’s popular adventure novel of 1887, She. As Marcus Hearn & Alan Barnes recount in The Hammer Story, it actually took a few years before the studio could enlist an American partner for what promised to be an expensive venture: MGM finally stepped up when Universal would not, and She was ultimately filmed for £323,778, far above the price tag for the typical Hammer programmer. It was shot in the studio’s anamorphic “Hammerscope,” capturing the wide desert landscapes of Israel (the film is set in Palestine, relocating the African setting of Haggard’s original). Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, the studio’s horror stars, both took supporting roles, but overshadowing their presence was Ursula Andress, Dr. No‘s Honey Ryder, in the starring role of the immortal Ayesha, “She Who Must Be Obeyed.” The posters proudly proclaimed her “The World’s Most Beautiful Woman!” above the three towering letters, S-H-E, built out of stone Ben Hur-style. Everything about this movie was going to be big, in the grand Cecil B. DeMille tradition.

Hammer Films had grown steadily since the box office breakthroughs of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). Distributors knew that the British studio’s genre product was reliably classy and literate, but also sexy and violent; they certainly knew how to fill seats and please audiences. By the mid-60’s, Hammer producers Michael Carreras and Anthony Hinds were ready to swing for the fences: a Hollywood-style spectacle, with a bigger budget than the thrifty studio would typically allow. Hammer settled upon a known property, H. Rider Haggard’s popular adventure novel of 1887, She. As Marcus Hearn & Alan Barnes recount in The Hammer Story, it actually took a few years before the studio could enlist an American partner for what promised to be an expensive venture: MGM finally stepped up when Universal would not, and She was ultimately filmed for £323,778, far above the price tag for the typical Hammer programmer. It was shot in the studio’s anamorphic “Hammerscope,” capturing the wide desert landscapes of Israel (the film is set in Palestine, relocating the African setting of Haggard’s original). Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, the studio’s horror stars, both took supporting roles, but overshadowing their presence was Ursula Andress, Dr. No‘s Honey Ryder, in the starring role of the immortal Ayesha, “She Who Must Be Obeyed.” The posters proudly proclaimed her “The World’s Most Beautiful Woman!” above the three towering letters, S-H-E, built out of stone Ben Hur-style. Everything about this movie was going to be big, in the grand Cecil B. DeMille tradition.

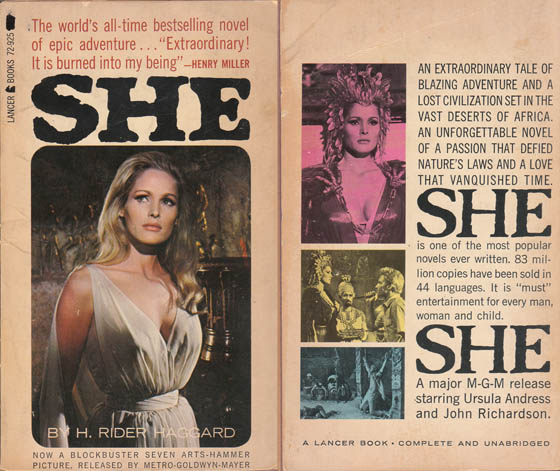

Front and back of the Lancer paperback movie tie-in edition of H. Rider Haggard's novel.

At least, that’s what the film’s overheated promotion would lead you to believe. In reality, the film is nothing like the spectacle of either Ben Hur (1959) or Cleopatra (1963). No mammoth sets, and the extras don’t number in the thousands. Beyond the casting of a (temporary) A-lister, and some welcome location footage, there isn’t much about She that’s radically beyond Hammer’s typical output. It’s still pulpy as hell, and the film’s central set – Ayesha’s throne room – isn’t nearly as impressive as it ought to be. It is, in fact, a little claustrophobic, particularly when packed with extras dressed as Roman centurions and African natives. But perhaps you need a small room if you want your extras to look like a cast of thousands.

Job (Bernard Cribbins), Leo (John Richardson), and Holly (Peter Cushing): three men looking for adventure in Palestine.

In the Hammer tradition, the details of the source novel are lightly tossed in a mixer for one minute before serving. Much of the first half of Haggard’s book is discarded, or at least greatly altered. Gone are a compelling first couple of chapters in which Ludwig Horace Holly (who, according to the book’s description, should look a little more Oliver Platt than Peter Cushing) receives the dying wishes of his handsome friend, Vincey: to care for his son, Leo, and raise him as his own, until he turns twenty-five, at which point they should together open a sealed casket and follow the instructions of what they find within, which will guide Leo Vincey to his destiny. Those materials, when opened, reveal Leo’s heritage: his ancestor is the Egyptian Kallikrates, who was murdered by his jealous wife, but it is said that the wife later attained the secret of immortality, and still awaits the return of her deceased husband, to make amends and live in ecstasy for eternity. Through the generations the descent of Kallikrates have tried in vain to find her, though Leo’s late father believed he had gathered enough clues: that she rules over a tribe in East Africa, almost inaccessible to explorers. Leo enthusiastically embarks upon the voyage, and Holly, overcome with curiosity, follows, along with their comic-relief valet Job. In the film, we meet our three protagonists, war veterans, in a club in Palestine drinking liquor while being entertained by some very scantily-clad belly-dancers. They’re not pursuing any ancestral destiny; they just want to look at pretty girls. Here Leo (John Richardson) meets the beautiful Ustane (Rosenda Monteros), who delivers word to her mistress, Ayesha (Andress); and though it takes almost half the novel before we finally meet the title character, who’s sequestered in a lost city within a forbidding mountain range, in David T. Chantler’s expeditious screenplay she comes to Leo immediately. Hammer just couldn’t wait to get their beautiful starlet on the big screen.

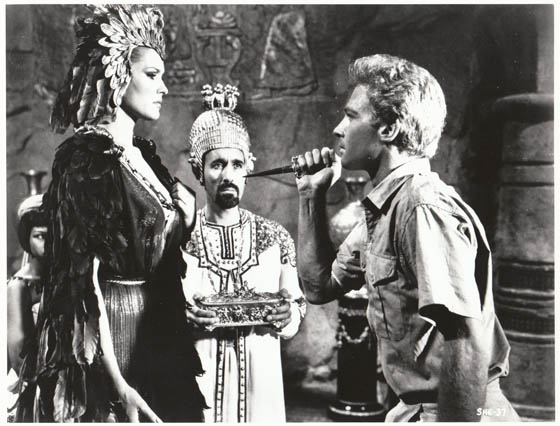

Ayesha (Ursula Andress) visits Leo to see if he is truly her husband reincarnated.

Now, I have major problems with this plot rejiggering. Much of the pleasure of Haggard’s novel comes in the thrill of discovering unexplored lands; Ayesha, with her seductive beauty (so powerful, in the book, that a man cannot look at her directly without falling desperately in love – so she covers herself in gauze like a mummy), is the reward at the end of the journey. Chantler’s screenplay moves Ayesha’s kingdom so that you only need to go south from Palestine, trudging through a desert for a few days before arriving; so simple is the journey that Ayesha makes it herself. This greatly devalues the peril of the quest. Further, when she greets Leo, she kisses him, and then tells him that if he’s truly Kallikrates reborn, he’ll come visit – so toodles for now. Keep in mind that this is a woman who has been waiting thousands of years for her lover to come back. She keeps his preserved corpse in her palace, so she can never forget his face. Leo Vincey looks exactly like Kallikrates. By rights she ought to tie him to a bed right then and there, and have her way with his studly self all through the weekend. But Andress, who delivers her lines without much conviction, merely departs with her servant Billali (Lee) at her side: come see me tomorrow, if you want; you might need camels.

Leo and Holly stop at an oasis on the road to Ayesha's lost city.

Luckily, once you’re past this rather unbelievable plot point, She notably improves. The journey through the desert evokes Lawrence of Arabia (1962) – director Robert Day (The Green Man) even steals one of that film’s most famous shots: a mysterious figure appearing gradually in the distance, like a mirage drifting slowly into the tangible. But Day has the class to superimpose a cheesecake image of Andress with her arms seductively outstretched; ostensibly, Leo’s hallucination, but also the director reminding us, “Don’t worry, there’s more Ursula Andress to come! The world’s most beautiful woman, don’t you know!” It should be said, however, that in one scene Day uses the same technique to achieve some genuinely poetic cinema: Leo sees the vision of Ayesha in the waters of an oasis; he reaches out and touches the water longingly, but only causes the image to depart. The director pans up, up, past rippling water lit almost electrically white, to find the reflection of palm trees swaying in the breeze. This is what pulp fantasy ought to look like. Composer James Bernard also rises to the occasion – though, as any Hammer fan knows, he was seldom a slouch. His ethereal main theme, “Ayesha – She Who Must Be Obeyed,” and the martial “Desert Quest,” are spellbinding in the classic Hollywood style. Bernard was always writing his scores to the budgets that Hammer couldn’t afford: he blessed their films (despite names like Taste the Blood of Dracula and Frankenstein Created Woman) with lush, romantic themes; he was the studio’s Bernard Hermann, its Erich Wolfgang Korngold.

Ustane (Rosenda Monteros) tries to protect Job and Holly from the Amahagger tribesmen.

Action arrives in the form of some camel-riding Bedouins who engage in a gunfight with Leo, Holly, and Job. A word about Job: the understated Bernard Cribbins is excellent in the role, and an improvement upon the source material; unlike Haggard’s character, Cribbins can handle himself in a fight, and he has a witty rapport with Richardson and Cushing that stands as a highlight of the film. After the shootout, our heroes find themselves without camels, and stumble through the desert on foot while their water supply dwindles. Ustane, who fell in love with Leo as soon as she set eyes on him back in the city, rescues the adventurers from the perils of the desert. She tends to their wounds, and guides them to the mountain kingdom of Ayesha, where they encounter the Amahagger, a tribe of Africans who worship their white queen (in case you had any doubt that this story was written in the 19th century). The tribesmen tie Leo to a post to sacrifice him, which is delayed by a dance number as elaborately choreographed as those in Hammer’s Slave Girls (1967). (I get the feeling that Michael Carreras loved this stuff.) Billali arrives to rescue them, and allows the lovestruck Ustane to accompany Leo into the city itself – a decision which has consequences. When Ayesha realizes that she has a rival, she has Ustane placed in a cage over a smoldering lava pit which happens to be in the center of her throne room. (Steven Spielberg and George Lucas later borrowed this idea for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.) This follows a few days of smooching and heavy petting with Leo, so Leo is in straits when Ayesha asks him to choose between them. Who will he let perish? I would have picked Ustane in a heartbeat; Leo, alas, goes for the icy blonde.

A publicity still depicts Leo confronting Ayesha over the life of Ustane, while Billali (Christopher Lee) looks on.

H. Rider Haggard focused his novel on the power of physical beauty: Holly, who narrates, cannot help but fall in love with Ayesha, nor can he help feeling jealous when he sees Leo receiving her affections. His great intellect and chaste nature crumble when confronted with her seductive power. But it’s Ayesha’s vanity which is her undoing; having received eternal life from a pillar of flame that cycles through the bowels of the earth, she steps into it a second time – which reverses its initial effect. She becomes a withered corpse, in such a horrifying transformation that Job dies of fright (again, he was a milquetoast in Rider’s hands); Leo and Holly, who were about to be seduced into stepping into the flame, have second thoughts after Ayesha perishes. Hammer’s adaptation once more fiddles with Haggard’s text, but not to the film’s detriment. Leo steps into the flame while holding Ayesha’s hand; after she perishes, it’s too late for him to change his mind. He’s an immortal. While Bernard’s music rises, Holly abandons the tunic-clad Leo in the mystic chamber; he will wait centuries, as Ayesha did, for her to be reborn. It has its own poetry, which isn’t actually that far removed from Haggard’s intentions; since at the end of his book, Leo and Holly know they can never fall in love with another woman, and so begin a vain quest to find her reincarnated form. Both versions of She end unconsummated; the characters as empty as preserved corpses.

Ayesha's youth is stolen back by the magical flame.

The film was a box office success, and received largely positive notices. A sequel was produced, albeit belatedly, called The Vengeance of She (1968), for which John Richardson returned, though not Ursula Andress, who was quick to put the film behind her. As with the original She, the marketing campaign for the sequel centered upon its glamorous female star, in this case a Hammer “discovery,” Olinka Berova of Czechoslovakia. The languidly-paced follow-up takes its time getting its heroine back to the lost city, where she learns she’s the reincarnation of Ayesha. Though not without some interesting moments, it’s a peculiar little film, and about on par with another Hammer fantasy, The Lost Continent, produced the same year: both films seem strangely unfocused, as though it’s not exactly clear what is at stake or why the audience should care. Haggard actually did write a sequel, Ayesha: The Return of She, which takes place in Tibet to bolster its reincarnation theme; The Vengeance of She is unrelated. Today, the 1965 She is mostly of interest to fans of either Hammer or Ursula Andress; if you’re in either camp, the film is entertaining. It can’t, alas, touch the beauty and splendor of the 1935 adaptation produced by Merian C. Cooper of King Kong fame, scored by Max Steiner, and starring Randolph Scott as Leo, Nigel Bruce as Holly, and Broadway star Helen Gahagan as Ayesha – her only film role. This She, much more faithful to Haggard’s book, at times achieves the look of a Maxfield Parrish painting. (A DVD was released by Kino a few years ago.) But Hammer’s She suggested a new direction for the studio, one which would prove fruitful: they called it “Hammer Glamour.” After She they pursued Raquel Welch, and once they dressed her in a fur bikini opposite some stop-motion dinosaurs (courtesy Ray Harryhausen), they’d have another hit on their hands: One Million Years B.C. (1966). For a little while, at least, the studio seemed to have perfected a formula all their own.