Kaneto Shindo, who turns 99 this year, established one of Japan’s first independent production companies, Kindai Eiga Kyokai, and – working outside the system – was able to present edgier fare. It’s difficult to imagine, for example, a darker and more daring work for the Japan of 1964 than Onibaba (Demon Woman), and it helped open the gates to a new kind of cinema in the decade to come. Based upon a Buddhist fable, Shindo’s film takes its time getting to the key element which will turn the story from a bleak, quasi-documentary on peasant life in the 15th century – when samurai warred for domination and burned cities, leaving the poor to scrabble for food or die – into a true horror tale worthy of Poe. But look closer, and the horror is there from the start. We see a dark, round pit in the center of a field of swaying suzuki grass. An almost-haiku tells us: “The hole, deep and dark. Its darkness has lasted since ancient times.” Then the score pounds upon the soundtrack while the opening titles roll: improvisational jazz wedded to something more frighteningly primitive. As the film progresses, the music by Hikaru Hiyashi (who scored Shindo’s The Naked Island) will settle for raw percussion and human screams. It’s that kind of movie. We see two samurai battle within the tall grasses, and just when a victor emerges, panting in exhaustion, a spear strikes out from behind and kills him. Out of the grasses come two women, who leap upon the men and strip their bodies of the armor. Then, without saying a word, they drag the bodies to that “deep and dark” hole, and shove the naked men over the edge. They’ll take their prizes off to a sleazy fence named Ushi, all for the sake of some millet, so they won’t starve. It’s a routine; you get the impression they do this every week, and long for another wounded samurai to wander into their deadly field. If this were a more straightforward horror film, they would clearly identified as the monsters. But no one in this film is untainted by corruption.

Nobuko Otawa and Jitsuko Yoshimura as the two peasant women, dragging another kill to the bottomless pit.

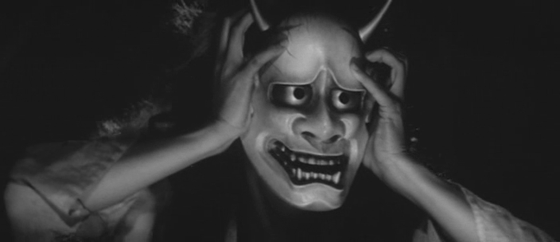

We learn that the younger woman (Jitsuko Yoshimura, Pigs and Battleships) is a wife abandoned by her husband, gone off to war to fight as a samurai; the older woman (Nobuko Otawa, Children of Hiroshima) is her mother-in-law. Fittingly, the mother-in-law wears a kimono patterned with the image of a crab: these two women, living by a the river and in a muddy swamp, scuttle and scavenge. The tale properly begins when a wandering samurai, Hachi (Kei Satô, Harakiri), arrives at their hut, announcing that the man for whom they’ve been waiting – named Kichi – is dead. Hachi is a crass slob, and leers over the woman whom he claims is now a widow. Gradually, she begins to succumb to his advances, possibly out of loneliness, but certainly out of a need for survival. He can provide for her, so she has no choice; almost greedily, she gives in to lust. The mother-in-law disbelieves Hachi, and is as appalled to see her daughter-in-law cave to possible adultery as she is anxious to keep someone so vital to her own survival in this muddy field. One night, while her daughter-in-law is off sleeping with Hachi, the old woman encounters a samurai with a demon-faced mask. He needs guidance through the field, which she reluctantly offers; when she inquires about the mask, he tells her that it’s meant to strike fear in the heart of his enemies – and also that he cannot show her his true face, for it is too beautiful for her to withstand. But the old woman sees this stranger as an opportunity…a chance to put things back to the way they were before Hachi’s arrival; with a cold-hearted calculation she begins to enact her scheme.

Nobuko Otowa as the mother-in-law in "Onibaba."

Onibaba is a most feral film. Its characters act more like animals than recognizable human beings; we feel a voyeuristic queasiness at seeing humanity at its lowest, with not a single likeable character in sight. (The character of Kichi’s wife becomes the most sympathetic, but only by default.) Director Shindo delivers this effect not just through the brutal score, but through the movements of the two women, close-ups of their delirious, hungry eyes, and manic shots of the two lovers running ecstatically through the tall grasses. The story, like so many fables, relies upon a repetition that builds toward a calamitous interruption: each night Kichi’s wife rises from the bed, carefully studying her sleeping mother-in-law, then creeping out the door before sprinting through those grasses toward Hachi’s hut – orgasmically. (When she finally encounters something waiting for her, rising suddenly out of the grasses, it’s genuinely hair-raising.) The film is dripping with sex. Hachi openly leers at the girl’s bare legs while she works by the side of the muddy river. In a movie that couldn’t possibly be more Freudian, he collapses, fraught with his unconsummated desires, at the edge of the dark pit and moans, “I want a woman!” Even the mother-in-law is not free of lust. In one moment she embraces a tall, barren tree while the camera pans up, up, up its long trunk and pointed branches. With greater frequency as Onibaba wears on, the actresses are partially nude. One of the key images in the film is Kichi’s wife lying on her back in the hut at night, her breasts exposed, damp with sweat, as she anxiously awaits the moment when she can run free through those grasses to her lover. Otowa, who was the wife of the director and his frequent star, plays the mother-in-law with a daring commitment to the film’s ungarnished texture; in one moment, topless, she towels off her armpit and then her face before alternating once more between that sinister smile and (default) scowl. This approaches the gritty peasant cinema of Pasolini, but with none of his romanticism. Ostensibly the film is a morality tale, but one custom-fit for a decade of sexual liberation. After such a long build-up, the ending is abrupt, but almost absurdly satisfying.

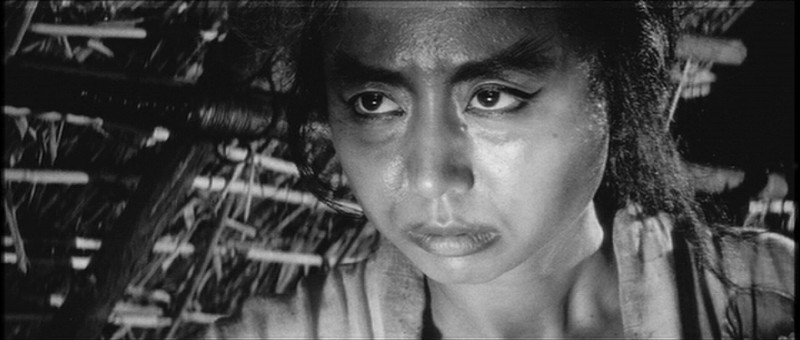

"Kuroneko": the ghost of Shige (Kiwako Taichi) seduces another samurai victim.

Four years later Kaneto Shindo brought audiences a follow-up, Kuroneko (Black Cat, 1968), but this horror tale trades much of the previous film’s grime and grit for a more abstracted visual poetry. It suits the story. Kuroneko begins with a shocking scene – a gang rape of two peasant women by an army of samurai – but you’ll notice it’s less explicit than it might have been handled in Onibaba. The unconscious women are left to perish in the burning hut, but Shindo lingers, until we see the smoldering remains, and the two victims, covered in burns and bruises, lie dead as their pet, a black cat, crawls over their bodies and licks their faces, and then the blood of their wounds. Once more we’re treated to an evocative, experimental score by Hikaru Hiyashi – at times it resembles the growls of a restless cat – but the environment of this film quickly becomes more overtly dream-like, and we’re not precisely sure of the rules of this reality. Late at night, a samurai comes to Rajomon Gate. There he sees a woman (Kiwako Taichi) materializing suddenly in the darkness, dressed in a white kimono, holding a hood over her face. She asks to be escorted back to her home, which lies deep in a bamboo forest. He obliges, seduced by her beauty, and travels through a fog to a house occupied by an older woman (once more, Nobuko Otowa). They give him some strong sake; the older woman asks after her son, who has gone off to fight in the wars – shades of Onibaba. Then she departs, and the drunken samurai takes the younger woman to bed…where she suddenly strikes at him like a cat, and rips his throat to bloody shreds. The mother waits in the darkness, watching the murder enacted by silhouettes. At dawn, the ghost-house dissipates back into ruins, upon which the samurai’s corpse rests.

Kichiemon Nakamura, as war hero Gintoki, sports his kill to the leader of the samurai.

The murders repeat, which Shindo protrays as a cyclical series of images: the samurai arriving by horseback at the gate; the young woman appearing – sometimes back-flipping through the air like wire-fu; the ride back through the bamboo forest; the sake; the seduction; the spilled blood. When a young samurai named Gintoki (Kichiemon Nakamura), calling himself “Gintoki of the Grove,” rides into the city with the prize head of a fearsome enemy warrior, his leader, Raiko (Kei Sato), cares more about the publicity he can drum up with such a war hero than the fact that Gintoki’s entire army has been lost to battle. And it’s really just a publicity stunt that he asks Gintoki to go to Rajomon Gate and slay the monster that’s been ripping out the throat of so many samurai. The young man obliges, but when he rides out to the gate he encounters a ghost who bears an uncanny resemblance to his wife, Shige, whom he’d presumed was killed while he was away at war. When he follows her back to her home, he finds that the older woman looks exactly like his mother. He demands that they reveal their true identities, but they vanish into the air. Only after subsequent visits can he persuade the ghosts to linger; they claim they can speak nothing of their true selves. He says he won’t harm them; he becomes content with their rules, and the woman-who-might-be-Shige takes him to bed. He spends the evening unharmed at her side, but is told to leave before dawn. Raiko impatiently awaits news of the monster’s destruction, but Gintoki returns empty-handed day after day, even as his face grows paler, his body more frail. Then one night he learns the truth of a pact that his lover ghost has made, and he finds himself compelled to follow Raiko’s orders to their desolate ends.

The ghost of Gintoki's mother (Nobuko Otowa) pays a final visit to her son.

Kuroneko is a distorted mirror-image of Onibaba, once more following a triangle of tormented souls in an age of samurai which Shindo is determined to strip of all traces of glory and honor. But while the supernatural happenings are more direct than in the former film, the dread is more existential, and almost suffocating. Gintoki’s wife and mother have become fused with the identity of a demonic cat, and have sworn an oath to the “god of evil,” taking vengeance on every wandering samurai. That oath can’t hold Gintoki as an exception, though as the story wears on, we see the two women struggle vainly against that oath, just as the samurai tries to neglect his oath to his boss, Raiko. Ultimately they’re all doomed by their promises, and one of the many Buddhist hells awaits them; for Gintoki, it’s a hell on earth. With these two unconventional horror films, Kaneto Shindo portrays a very human kind of horror, where the characters are trapped by their own decisions – and driven to do so by an impoverished and merciless world. And the beauty is that the grimmer they become, the more graceful is Shindo’s touch: true black magic.