“Tin-to-re-ra. The Americans like you say, ‘tiger shark,'” helpfully explains the blond Mexican shark-hunter at the start of the film, who is leering at two girls in tight tops and bikini bottoms. But what’s actually important in this moment is the leering. Tintorera (aka Tintorera: Killer Shark, 1977) is a Mexican Jaws cash-in which almost forgets to have a killer shark in it: this is a problem. Instead, the film’s point-of-view is best expressed by our hero, Steven (Hugo Stiglitz of Nightmare City), when his fellow shark-hunter bitterly curses all tiger sharks. “Maybe you hate them, but I feel sorry for them. But then, that’s life. Actually, I’d rather hunt the tintorera in bikini that walks along the beach!” Cut to a shot (through binoculars) of girls in bikinis walking along the beach. The bearded Steven, standing on his private boat and stalking his prey, nods and grins at the camera.

“Tin-to-re-ra. The Americans like you say, ‘tiger shark,'” helpfully explains the blond Mexican shark-hunter at the start of the film, who is leering at two girls in tight tops and bikini bottoms. But what’s actually important in this moment is the leering. Tintorera (aka Tintorera: Killer Shark, 1977) is a Mexican Jaws cash-in which almost forgets to have a killer shark in it: this is a problem. Instead, the film’s point-of-view is best expressed by our hero, Steven (Hugo Stiglitz of Nightmare City), when his fellow shark-hunter bitterly curses all tiger sharks. “Maybe you hate them, but I feel sorry for them. But then, that’s life. Actually, I’d rather hunt the tintorera in bikini that walks along the beach!” Cut to a shot (through binoculars) of girls in bikinis walking along the beach. The bearded Steven, standing on his private boat and stalking his prey, nods and grins at the camera.

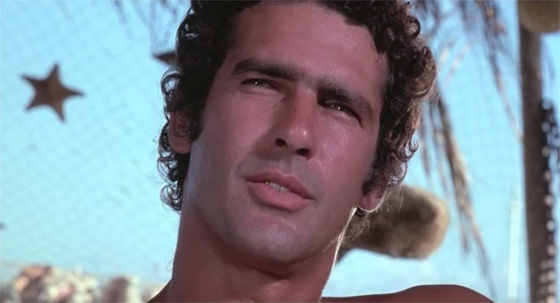

Patricia (Fiona Lewis) is awkwardly courted by Steven (Hugo Stiglitz).

There are dozens of girls in bikinis, but for some reason Steven immediately becomes obsessed with a fully-clothed brunette on a scooter who’s on a road a good distance behind those girls in bikinis, and rather hard to see. Nevertheless, he soon discovers her lounging on a beach, and finds that, just as his instincts told him, she looks very good in a bikini indeed. Her name is Patricia (Fiona Lewis – a British actress, since this is a British co-production), and she’s intrigued by Steven’s clumsy pick-up lines and dead-eyed stare. Soon they’re having dinner on his yacht, sipping champagne, and she says dreamily, “I’m happy here.” After an evening of making love, they explore the Mexican shoreline, which leads to this self-searching discussion about the meaning of love (note the exquisitely crude transition at the end of the scene, which I have left intact since it represents the entire film so perfectly):

Despite Steven’s haunting beard and atrocious dubbing, Patricia casually abandons him for the beach’s top hunk, shark-hunter Miguel (Andrés García). In response, Steven hits Miguel in the face, Patricia calls him a “stupid fool,” and Steven is socially ostracized. That night, Patricia makes love to Miguel, then takes a nude swim, where…wait for it…she’s killed by a tiger shark. When Miguel awakens, he presumes she merely ditched him, just as she did Steven, because…I mean, women, am I right, guys? Later, Steven encounters Miguel in a cafe sharing drinks with two pretty young ladies. “Watch out, the wild man has arrived!” Miguel impishly shouts, picking up a chair and holding it between them in defense. “Do you always go around playing the part of the clown?” wet blanket Steven asks. Miguel responds, “I’m just a happy-go-lucky guy,” and relaxes casually into his chair. Ultimately Steven is won over (without changing his dour facial expression), less by the happy-go-lucky Miguel and his teeny-tiny speedo, than by the fact that the two attractive women at his side are evidently very promiscuous. By the end of the night, they’re all abandoning their clothes on the beach and swimming naked to Steven’s yacht, partying hard, and having sex in hammocks before swapping partners. This is all set to an easy-listening score by Basil Poledouris, incidentally. The composer (who died in 2006) is best known for Conan the Barbarian (1982) and other big-muscled films of the 80’s, but glancing at IMDB, it’s apparent he was also the go-to composer for anything involving beaches and swimsuits: Big Wednesday (1978), The Blue Lagoon (1980), and Summer Lovers (1982) were all his work. His music here is a combination of light jazz and disco, but he steps up the effort by composing a song, “Together Until Goodbye,” sung by one Kelly Stevens. The endless and lethargic song becomes the romantic ballad of the film, since this is really a love story; it just happens to have a killer shark in it, somewhere…oh yeah, remember? Patricia was killed. That happened.

Andrés García as Miguel, ladies' man.

After their debauched night, Steven and Miguel form a blossoming bromance. Then into the picture steps another British girl, Gabriella (Susan George of Dirty Mary Crazy Larry). They both like her a great deal, and – you know what? – she likes them too. Equally. As David Crosby wrote, “It’s plain to see/Why can’t we go on as three?” This leads to a series of montages which actually take up most of the film. We see them gazing at one another lovingly, and sailing across the beautiful blue waters while gazing at one another lovingly. We even get a hint of the logistics surrounding their sexual encounters, but this is discreet and passed over pretty quickly, to the audience’s relief. One particular montage involves them posing while taking pictures of one another, and having their picture taken by a kindly old Mexican woman, and this is very important because the sequence will be replayed over the ending credits in full. Then, one day, Miguel is killed by a tiger shark while diving, and Steven and Gabriella are witnesses. Steven delicately suggests that they could continue a relationship without Miguel, but Gabriella is as disgusted by the idea of ignoring Miguel’s death as she is the notion of a traditional two-person arrangement, which is for squares. She departs the country and the film.

Miguel goes shark-hunting.

A despondent Steven returns to the beaches to pursue more women. At a beach party, he encounters the two promiscuous ladies from earlier in the film, and they take shots out of a conch shell filled with “the favorite drink of Emperor Montezuma”: tequila, cocoanut juice, rum, and green tea (“for rheumatism”). Then the partiers strip naked and dive into the water, where suddenly the plot arrives, and a tiger shark commits mass slaughter. Shaken out of his stupor, Steven goes on a quest for revenge, and since there’s only about ten minutes left in the film, this shouldn’t take long. He teams up with that blond, leering shark hunter from the start of the film, and they pursue their quarry in a murkily-lit climax.

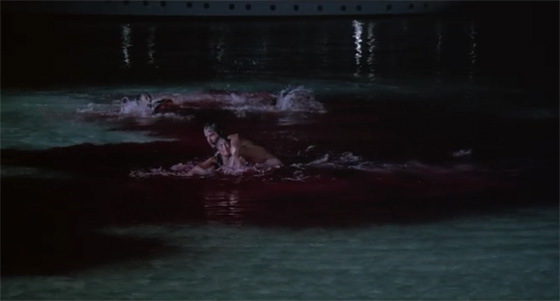

A massive skinny-dipper massacre as the tiger shark makes its belated move.

Tintorera was directed by René Cardona, Jr., a prolific Mexican director who made several films a year between the mid-60’s and 2000. The script, which doesn’t seem very interested in being Jaws, was co-written between Cardona and Ramón Bravo, a Mexican journalist, photographer, freediver, and tiger shark expert; he wrote the novel upon which Tintorera is based. But the finished film seems less interested in sharks than whether or not a ménage à trois can be sustained without jealousy causing the relationships to implode. The three carefree, tiny-swimwear-sporting lovers create a pact: no commitments, no falling in love – just enjoy yourselves and share your bodies equally while snooze-inducing disco music plays on the soundtrack. Is the tiger shark – cruel, murderous – the symbol of a closed-minded society which prevents the existence of such free-minded arrangements? In the end, Tintorera remains ambiguous, elusive – like the killer of the sea, rising swiftly and then disappearing once more into the dark depths. Note: Universal Studios sued the producers of another shark-driven exploitation film, Great White (1981), and succeeded in having the film withdrawn from the market. But they didn’t go after Tintorera, and I can kind of see why.