Viva La Muerte belongs on the shelf between Buñuel’s Viridiana and Pasolini’s Saló, but it is by far the angriest film I have ever seen. Shot during Franco’s regime, there is no way it could have been filmed in Spain (it was shot in Tunisia instead). Consider the scene in which a group of well-dressed students turn a corner to find themselves standing before a firing squad. The guns ignite. The boys fall…except one, who stands, a bullet in his stomach, shouting “I’m saved! I’m not dead!” “It’s the poet,” says the captain. “The faggot. Finish him off up the ass.” He places his gun behind the poet and fires. The victim is identified as none other than Frederico Garcia Lorca (killed in 1936), a man who could not even be discussed in Spain at the time this film was made.

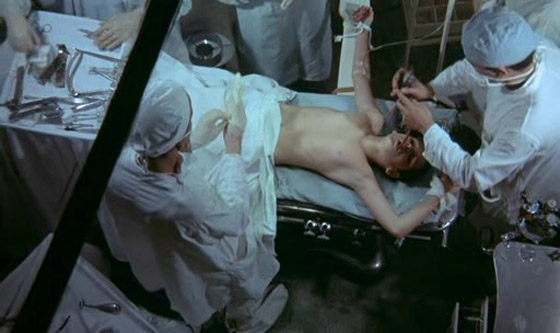

This moment, like all of the film, is witnessed through the subjective gaze of young Fando (Mahdi Chaouch), who has recently learned that his mother (Nuria Espert) reported his father to Franco’s partisans on suspicion of his leftist ideas. He has died in prison – a suicide, his mother claims belatedly. Fando doesn’t believe it for a moment. Viva La Muerte, the first film directed by playwright Fernando Arrabal, becomes a kaleidoscopic vision of the boy’s inner rage at his mother (as well as confused lust), uncle, schoolteacher, and Franco himself. He is surrounded by murders, denials, and repression, and his torment is reflected in feverish, harshly-tinted daydreams full of imagery that is funny, shocking, and horrifying, by turns (or at once). Standing before a lighthouse on a high hill, he pisses in the direction of the village and dreams that he’s flooding the whole town. He imagines his priest getting his testicles cut off by soldiers and being forced to devour them (and thanking God for the opportunity). He sees his schoolteacher as a pig in a habit, or his mother wallowing with him in the mud. But most often he sees his mother murdering his father in various ways, and the thought consumes him so entirely that it seems to feed directly into an illness, which gets him sequestered upon a boat with other sick boys. And the fantasies and nightmares continue.

Fando was first glimpsed in celluloid as a young adult in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Arrabal adaptation, Fando y Lis (1968). (Jodorowsky, of course, was responsible for what’s largely considered the first “midnight movie,” El Topo. Following El Topo‘s word-of-mouth success, some theaters programmed Viva La Muerte in the midnight slot to try to tap into the same audience.) Jodorowsky filmed the allegorical play without a script, working from memory; he was a good friend of Arrabal’s, and with cartoonist Roland Topor, whose illustrations are featured in Viva La Muerte, they had formed the Panic Movement in 1962. The group performed interactive street theater and valued shock and extreme imagery as a means of making their intellectual ideas viscerally experienced by the audience. Viva La Muerte is perhaps the best example of Panic, with its constant onslaught of unfettered anger and taboo-violating imagery (animals are killed on camera, and feces, blood, and incest figure prominently). It’s a difficult film to watch – physically. But it’s also upsetting on a political and an emotional level: Arrabal intends all of these reactions at once. This is a bomb lobbed directly at Franco’s nose. There is a through-line with poor Fando which may carry you far, and it’s worthwhile to take the trip to its very end. If you don’t, I’ll tell you what you missed: the final image is of Fando, wrapped in bandages from his surgery, carried out of Spain by the girl he loves (Lis?) on a cart…entering the wilderness of Fando y Lis. It seems to imply that it’s a prequel, but in fact offers a looking-glass image of the earlier film: in Fando y Lis, Lis is the cripple, and borne by Fando (who, despite his professed love, tortures and betrays her at every opportunity). It may help to understand that Fando is, of course, Fernando Arrabal, and if Fando y Lis takes place on a more psychological landscape, Viva La Muerte may be more strictly autobiographical. He was born in 1932, and witnessed the Spanish Civil War as a child. Don’t look for illumination on the DVD’s interview, however; he answers every question in the most abstract manner possible while positioning a chair in front of his face. Where was this shot? “In Tunisia, but I wanted to film in Atlantis. Or my mother’s womb.” And what is it all about? “It’s a prayer.” Well, that at least makes sense, but it’s the most savage prayer you could imagine.

[This post originally appeared on my old blog, Kill the Snark, in 2007.]