Since I just covered 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), this naturally leads us into Mysterious Island (1961), the film adaptation of Jules Verne’s sequel, which follows up on the fate of Captain Nemo and his Nautilus. Eventually. In the meantime, Ray Harryhausen, fresh off The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960), uses his visual effects magic to liven up Verne’s two-part novel, liberally adding giant monster battles, because, let’s face it, everything is better with giant monster battles. Since the film – produced by Harryhausen’s frequent cohort Charles H. Schneer – was made for Columbia Pictures and not the Walt Disney Company, when Nemo does show up, he’s played by a different actor (the great Herbert Lom), and the design of the Nautilus is just different enough to avoid a lawsuit. Although its budget was significantly smaller than the Disney version’s, the film was a hit with the matinee crowd, and to this day many still count it as their favorite of Harryhausen’s impressive resumé.

Captain Harding (Michael Craig) and Herbert Brown (Michael Callan) plot their escape from a Confederate prison.

The film begins with the siege of Richmond, Virginia, in 1865. Our heroes are Union soldiers in a Confederate prison: the cool-headed Captain Cyrus Harding (Michael Craig); Neb (Dan Jackson), a black soldier; and young Herbert (Michael Callan, looking a lot like Tommy Kirk), who’s handsome but neurotic. They stage an escape during a storm by stealing a hot-air balloon, and are joined at the last minute by a new prisoner, war correspondent Gideon Spilitt (Gary Merrill), and a Confederate soldier, Sergeant Pencroft (Percy Herbert), whom they hold captive. The exciting escape sequence is assisted considerably by the rousing score by Bernard Hermann. Hermann – perhaps the greatest film composer of all time – greatly enjoyed scoring the “Dynamation” fantasies of Harryhausen & Schneer; he’d provided memorable themes for The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and The 3 World of Gulliver, and would reunite with them again for the triumphant Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Unlike his nerve-jangling body of work for Hitchcock, exploring the realm of fantasy allowed him to tap into a more romantic, Rimsky-Korsakov vein. You can hear this shift as the prisoners approach the balloon (a convincingly-integrated model), and especially as they soar above the clouds, losing their course, and finding themselves over the ocean.

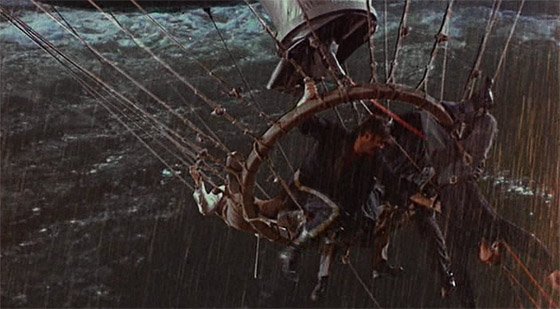

Our heroes scramble as the tempest brings down the balloon.

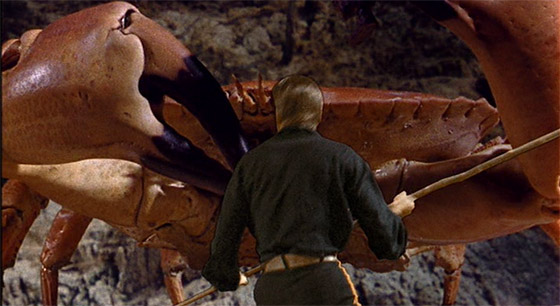

After an exciting sequence in which they’re forced to cut loose the basket and clutch desperately to the ropes beneath the balloon, they crash into the sea, and swim to the titular island, which announces itself with Hermann’s noble trumpets. Optically matted into the center of the island is a smoking volcano, and surrounding it are steeply-jutting mountains of rock and cradles of jungle. The landscape is rife with possibility; the viewer wants to begin exploring immediately. The party crosses the island to find any signs of humanity, but instead only encounter another beach, where a giant crab suddenly erupts out of the sand, snapping at them with its claws. This creature is one of Harryhausen’s finest stop-motion creations, though he actually used a real crab instead of molding one from scratch. He wrote in his book An Animated Life, “The reason for using a real crab was that nature had made such a good job of creating this complex creature that whatever I would come up with would never look the same. To avoid boiling the poor thing live in water, I had him professionally and humanely killed by a lady at the Natural History Museum in London. She took it apart and laid it all out on a board to show me how it fitted together. Later I ‘reconstructed’ it by mounting the pieces around the armature my father had built to my specifications.” He then used close-ups of live crabs for the shots of the snapping mandibles. The result is a gripping sequence which ends when the heroes flip the creature onto its back, then topple it into a boiling geyser; the next shot is of everyone dining happily on crab meat.

Harding battles Ray Harryhausen's stop-motion-animated giant crab.

Ennui is alleviated when two more castaways – females! – conveniently wash up on the beach (a third survivor of their shipwreck is dead on arrival): the elegant Lady Mary Fairchild (Joan Greenwood, Kind Hearts and Coronets), and her daughter Elena (Beth Rogan), whose carefully showcased legs become one of the major special effects of the film. Since this isn’t The World, the Flesh, and the Devil, the introduction of the opposite sex doesn’t turn our males against one another; instead, Elena and Herbert happily pair off: she, perhaps, attracted to his anachronistic Elvis Presley hair. He also overcomes his paralyzing fear when he saves her life from a giant prehistoric-style bird (Harryhausen intended it to be a “phororhacos,” though the explanation for its presence on the island was omitted from the final film). Soon they’re requesting the Lady Mary’s permission to get married. And although construction of a boat is lazily progressing, the castaways seem a lot more excited about their new abode, “Granite House,” a cave set high into towering cliffs, which they renovate (there are cobwebs and the skeleton of a pirate) into something a bit more homely, even constructing a pulley-operated elevator. Any resemblance to Swiss Family Robinson (1960) is not coincidental; Mysterious Island builds on the success of that Disney film just as much as it does 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

Elena (Beth Rogan) and Herbert are sealed into a honeycomb by a giant bee.

As a child I was terrified of bees, so the most effective sequence for me was always the arrival of the giant bees, who seal Herbert and Elena into a towering wall of honeycombs. The suspenseful sequence ought to be longer (really, the bees should pursue the characters after they escape), but you don’t really notice, because it transitions into a larger setpiece involving a pirate raid on the island, as Captain Harding and his men fire on the pirates from their position in Granite House. Then the pirate ship explodes – sunk by charges placed by Captain Nemo, who emerges from the ocean wearing a diving suit constructed out of giant seashells. Really, does pulp fantasy get any better than this? Herbert Lom’s belated arrival in the film as a white-bearded Nemo initiates a visit to the Nautilus, moored in an eerie cavern. The submarine is less ornately decorated than the one featured in 20,000 Leagues. Lom does, however, play Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D minor” at the organ somberly: a requirement if you’re playing either Captain Nemo or the Phantom of the Opera; and Lom has done both. Nemo’s explanation for why he created the giant flora and fauna on the island is only semi-convincing (he wants to eliminate world hunger, thus continuing his quest for ending war), but he initiates an exciting final act in which even more pulp elements are squeezed into the film, including an exploding volcano, a cephalopod attack (once again animated by Harryhausen) in which our seashell-suited divers strike back using rifles that fire bolts of electricity, a desperate bid to raise the sunken pirate ship, and even the exploration of an underwater city that might very well be Atlantis. All of this is thrown at the viewer so breathlessly that Mysterious Island moves from the realm of Jules Verne into that of 1930’s pulp serials, or Flash Gordon comic strips. In other words, it’s superb.

Herbert Lom as Captain Nemo

Filmed in Shepperton Studios in England (thus the presence of so many British actors) and on the coasts of Spain and beneath their waters, Mysterious Island has a rich, expansive look which has added to its enduring appeal over the decades. Director Cy Endfield, who would next direct Zulu (1964), complements Harryhausen’s effects work with memorable performances from the cast; you come to know these characters quickly, and root for them as this busy little island unleashes its many challenges upon them; thus the film has pleased a broader audience than just “monster kids.” The new Blu-Ray from Twilight Time, in a limited edition of 3,000 units (available, until they run out, from Screen Archives), is recommended, though with a few reservations. The only supplements are an isolated score (which is welcome) and a theatrical trailer; gone are the featurettes from the Sony/Columbia DVD release, so you might want to hold onto that if you have a copy. As with all the Harryhausen films released on Blu-Ray, high definition doesn’t do many favors to his FX sequences: they can be excessively grainy, and the mattes show their seams; some shots of the elevator scaling Granite House are particularly wince-inducing. Still, the presentation is notably improved from previous home video incarnations, with vivid colors. The original mono soundtrack is included as an option, but the new 5.1 surround sound mix nicely showcases Hermann’s thunderous score. If you want it, act quickly. The next limited edition Twilight Time release, Fright Night (1985), will be released in December.