There was no reason to have a Monkees movie, particularly in 1968, when the band was severely out of fashion. But enough money had been made on the records and TV show that it could certainly be financed, and so was born Head, the first feature film from director (and Monkees impresario) Bob Rafelson, who would go on to raw dramas like Five Easy Pieces (1970), The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), and Stay Hungry (1976). Jack Nicholson, whose most recent projects were hippie exploitation – like The Trip (1967), which he wrote, and Psych-Out (1968) – would compile a script from the random ideas offered by Rafelson, Micky Dolenz, Davy Jones, Michael Nesmith, and Peter Tork. The result would be episodic, but not your typical episode of “The Monkees.” The humor would have a strangely unsettling undercurrent. If they were accused of being phony, they’d own up and detonate the artifice from the inside out. It was all there in the poem/song “Ditty Diego – War Chant”:

Hey, hey, we are the Monkees,

We’ve said it all before.

The money’s in, we’re made of tin,

We’re here to give you more.

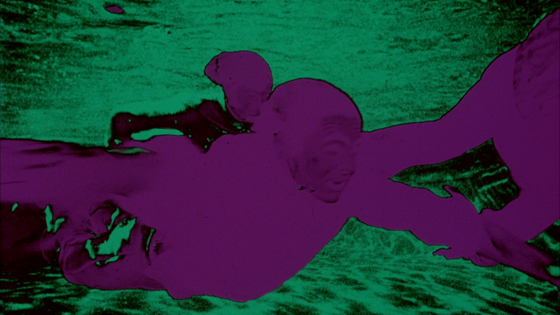

The Monkees swim to the psychedelic classic "Porpoise Song."

As they chant, television-sized images of scenes from the film – which we’re about to watch – stack on top of each other, all of it seeming to be conventional Monkees hijinks (in their Hard Day’s Night-aping style), but culminating in the notorious footage of South Korean General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner. That footage was from February 1st, 1968; only about nine months old by the time Head was released. To include the most famous snuff film of all time in a Monkees movie was something of a risk; but since the band’s sun had set anyhow, why not? Also included in Head: boxer and ex-con Sonny Liston, Mouseketeer Annette Funicello, Green Bay Packer Ray Nitschke, silicone injection pioneer Carol Doda (as “Sally Silicone”), Frank Zappa, and even the controversial erotic sculpture “Back Seat Dodge ’38” by Edward Kienholz, which can be glimpsed at Mike Nesmith’s birthday party. Anything controversial, scorned, or otherwise out-of-date was welcome for the Monkees’ going-away bash. The emcee would be Hollywood star Victor Mature, playing himself; part of the film is set in his hair. One interpretation is that the entire film takes place in (and around) Victor Mature’s head, thus the title.

Peter Tork, Davy Jones, Mike Nesmith, and Micky Dolenz film a special effects sequence for "Head."

The first time I watched Head, I was eager for some psychedelic madness, but still uneasy with the strange, strange brew that I imbibed. Revisiting the film with Criterion’s (gorgeous) 2010 Blu-Ray restoration, I found myself smiling and laughing a lot more. Any accusations of pretentiousness are batted casually away by the let’s-try-anything anarchic humor of Rafelson, Nicholson, and the Monkees. Micky engages in an epic battle with an uncooperative Coke machine in the desert, culminating with his blowing it up with a tank. Davy hams it up in a spot-on parody of 30’s and 40’s Hollywood boxing dramas (from Golden Boy to The Set-Up), and is terrified to the core of his being when he discovers a giant gazing eyeball in a medicine cabinet. Peter learns a valuable lesson about the nature of reality from a swami in a sauna. Mike is his usual wiseass self. All while they pass from one dimension into the next, tearing through the phony backdrops of sets and even arguing over the script with Rafelson, Nicholson, and Dennis Hopper, who play themselves in a very meta moment. None of it is Mel Brooks-level comedy; a stronger comic voice behind the script would have helped immeasurably. (Nesmith laments on the commentary track that he wished Rafelson would have used some of his “sharper knives,” though this film is hardly gentle.) But one of the strengths of Head is that, for all its unconnected sketches and constant disorientation, the film has a focused point of view. It turns a mirror toward the Monkees phenomenon, often damningly. At the end of the raucous Nesmith tune “Circle Sky,” the Monkees become mannequins, standing behind their instruments and torn to shreds by their fans. Time and again they become trapped in a black box – ultimately, they drown in one.

The soundtrack LP was intended to be a mirror to reflect the beholder's own head.

The film’s other strength – and perhaps its greatest – was its music. It may have been the end of the line, but the Monkees were better than ever. They’d developed into a touring band, playing their own instruments even if the record company insisted they use session players for the soundtrack. “Porpoise Song” bookends Head, set to brightly-colored solarized photography while Micky (and, later, all the Monkees) swim in the ocean after diving suicidally off “one of the finest suspended-arch bridges in the world.” Though the single tanked, the song, written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, has endured to become a classic of late-60’s psychedelia. Davy performs a respectable cover of “Daddy’s Song,” a high point of Harry Nilsson’s early songbook, and his dance with Toni Basil is a dazzling feat of editing thanks to Rafelson’s decision to splice together, rapid-fire, two different recitals – one with the pair dressed in white, the other in black. Commendably, Peter Tork composes two of the trippiest songs on the album (though they also sound the most dated – not necessarily a bad thing, depending on your disposition). Meanwhile, Micky’s vocals for “As We Go Along” are simply breathtaking; Ry Cooder and Neil Young play on the track. Nicholson edited together the soundtrack, using random snippets of dialogue from the film and editing them together into a pop art collage; listening to the album is your only chance to hear what a Jack Nicholson mixtape sounds like.

Mike is freaked out by his transdimensional birthday party.

Nobody asked for a Monkees film in 1968, so hardly anybody went – even when the advertising minimized the presence of the band, or, more frequently, didn’t mention them at all. Posters were hung and stickers distributed that showed only a photo of a man’s head, staring forward. If the intent was to hook the head-trip crowd – or even art-house buffs – one could only imagine their bemusement at receiving a belated Monkees motion picture. Naturally, it’s endured as a cult item; it had to. Audiences found it on late night TV or midnight movie screenings. Eventually, teenage girls were no longer the Monkees demographic; instead, they were rock historians and audiophiles mining 60’s esoterica, and naturally delighted to find something as bizarre and singular as Head. Now it’s in the Criterion Collection – go figure; the most unusual entry in Criterion’s indispensable box set America Lost and Found: The BBS Story, which chronicles the company founded by Rafelson, Bert Schneider, and Steve Blauner, who used the Monkees goldmine to kickstart a company that would bring us Easy Rider (1969), Five Easy Pieces, and The Last Picture Show (1971), among others. (Quite the phoenix to rise from those ashes.) Experimental, engimatic, and endearingly self-deprecating, Head stands on its own as one of the most genuinely mind-bending products of the late 60’s; if only the counterculture had noticed.