Here is how I first become conscious of Alien (1979). I was very young – no idea how young, but too young – and my family had innocuously left “Entertainment Tonight” on the television. This was back when ET covered movies, incidentally, and not just celebrity plastic surgery, sex scandals, and drug overdoses. A retrospective on Alien included an extended look at the notorious dinner scene in the film. John Hurt begins choking violently. Yaphet Kotto says, “Come on, the food’s not that bad.” Hurt starts convulsing, and his fellow Nostromo crew members push him onto the table, where he suddenly spasms so brutally that a bloody appendage erupts from his chest. Everyone just stops, stares. The infant alien creature, jutting from the cavity, blindly and slowly turns. Then it dashes off down the table and disappears, leaving John Hurt’s blood-spattered corpse behind. My eyes were several inches from my head.

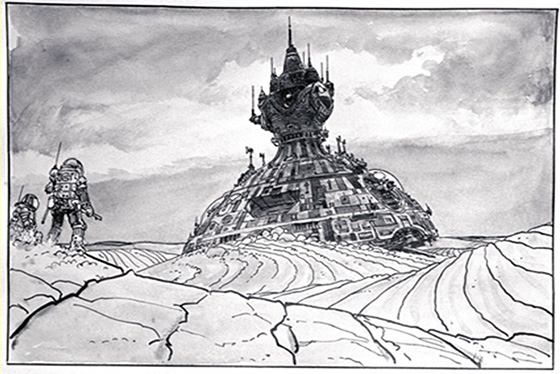

Concept art for the derelict craft by Moebius.

Memories are deceptive; ET may have edited the scene for broadcast, but I’m certain that was my first exposure to the film, because it marked me. It also spoiled me somewhat when I did finally watch it all the way through, many years later, though by that point I was pretty much aware of the entire plot of the film anyway. Alien is so embedded into pop culture that it’s impossible to avoid. (And the franchise continues to terrorize and fascinate youngsters. I continued the cycle of abuse when I was in high school, babysitting the neighbor boy, who was in elementary school. Aliens was on television. I’d seen it many times already, and figuring that we’d only watch the first forty-five minutes or so before he had to go to bed – and it doesn’t really get scary until later on, right? – then no harm would be done. Just before bedtime, Sigourney Weaver’s entire military unit was slaughtered. Time for bed. I learned the next day that his parents found him wandering the hallways that night, afraid to go to sleep, hunting for “aliens with acid for blood.” That was specific enough to get me into trouble.) Like so many teenage geeks, I obsessed over the Alien franchise, as well as Predator (1987), John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), etc. These R-rated science fiction/horror films were especially potent for me because I grew up on the softer stuff: the Lucas, Spielberg, and Dante films of the early 80’s. The subgenre which Ridley Scott helped launch was gritty, scary, and almost nauseatingly gory, so naturally it had a kind of punk appeal to a teenager, even if I expressed that by buying Aliens vs. Predator comic books and making comics of my own to hand out to classmates. Eventually my passion ebbed. Maybe it was the disappointing Alien³ (1992) that killed the love; or the fact that I was starting to get into “serious” films like those of Scorsese, Coppola, and Kurosawa. (As important as Alien was for me, a few years later Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, The Seven Samurai, and High and Low had opened a whole new world of cinema that I was anxious to explore.)

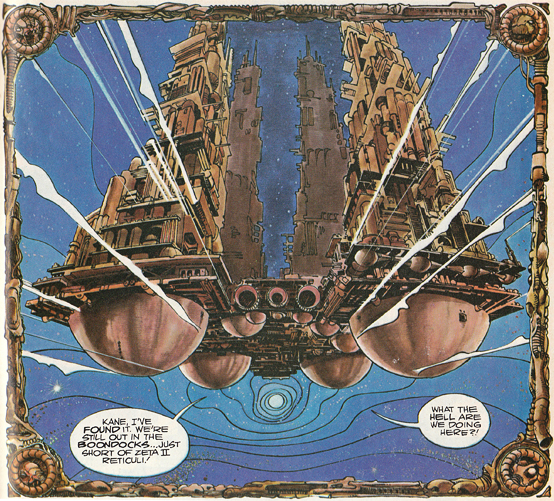

An excerpt from Walter Simonson's and Archie Goodwin's graphic novel adaptation of "Alien" was included in the May 1979 issue of Heavy Metal magazine.

But I still return to Alien, much more so than its immediate sequel, whose marines vs. monsters model has been endlessly imitated; to me, Scott’s film seems to be the more timeless. (Stylistically speaking, the true sequel to Alien is Blade Runner.) Watching it again, I realize that there is little which visually dates the film – surprisingly so for 1979. Only in the small chamber where Tom Skerritt and Sigourney Weaver consult their ship’s computer, “Mother,” does the film show its age: a computer here is nothing but a keyboard, an MS-DOS style interface, and panels upon panels of pointlessly blinking lights. (But it can still interpret the phrase “WHAT’S THE STORY MOTHER?” – a sentence which would probably send a vexed Siri to Google “Story Mothers.”) By continually redressing the long stretches of Nostromo corridors constructed on set, Scott convincingly creates the feeling of a claustrophobic and labyrinthine spaceship. Every nook and cranny is decorated with evidence of a long occupation in space; essentially it resembles the interior of a deep-sea oil rig, which is more or less what the Nostromo is. Note, for example, the scene in which Ian Holm attacks Sigourney Weaver in some crew member’s cabin: topless pin-ups decorate the wall, a detail easy to miss given that the focus of the action is elsewhere; and an odd little toy dangles from the ceiling (batted out of the way during the struggle), perhaps in memory of a child whose black-and-white photo is briefly glimpsed on the opposite wall. Scott’s attention to detail is thorough, which is helpful given that the story, by Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett, is intended to be as simple and straightforward as possible – a grisly antidote to the Star Wars frenzy, it would be the equivalent of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in space, with an obvious debt to forefathers The Thing from Another World (1951), It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958), and Planet of the Vampires (1965).

The HR Giger Museum Bar in Switzerland resembles the artist's designs for "Alien."

In some ways the film belongs as much to surrealist artist H.R. Giger as it does to Scott. His designs for the alien’s life-cycle never cease to be fascinating; it’s clear that one of the goals of the film was to provide a genuinely alien creature, something which developed in an environment unlike Earth. (One of the strengths of James Cameron’s sequel is that he accepted that the alien’s life-cycle should provide the story’s central thrust: an Alien film should be a mystery constructed around biology.) It’s difficult to recreate that engrossing first viewing, when you don’t know what the crew is dealing with, or what the creature will transform into next. A highlight of the film is the discovery that the “facehugger” alien has acid for blood, and the race from one deck to the next as the crew helplessly watches as the blood eats straight through the ship. One particular stage of the creature’s biology was omitted from the final print of the film, though it was reinstated for the 2003 alternate cut: late in the story, Weaver’s Ripley discovers that the creature is cocooning its victims like a spider (the Alan Dean Foster novelization retained this version of events). All of these strange details are really the meat of the story; it helps distract from the film’s clichéd elements, such as the perpetually unhelpful cat Jones, springing out of dark corners and generally acting as a false alarm. No, it’s the world you care about, as thoughtfully constructed as anything in Star Wars – Scott and Giger create a believable space for the viewer to inhabit, which adds to the terror. The set constructed for the “space jockey” – the bridge of a massive alien ship, whose throne is occupied by a fossilized creature that has grown into the seat, a tell-tale cavity in its chest – is faithfully close to Giger’s colorless, biomechanical illustrations, and thus has the authentic feel of a waking nightmare. When Veronica Cartwright suggests they leave immediately, she’s the audience surrogate; on this viewing I found myself wondering: if this is truly alien, how do they even know this is a ship? Couldn’t this be like that Philip K. Dick short story where the astronauts step into what they think is a ship, but turns out to be a creature’s mouth? Giger and Scott further prey upon the viewer’s subconscious by making the alien and its methods queasily sexual. The reproductive cycle is perverted by its birth straight through Hurt’s chest. The alien itself is phallic (particularly in its “chestburster” state), grotesquely so, and its assault on Cartwright has the uncomfortable overtone of rape. A true horror film, Alien may tease monster movie conventions, but is focused upon genuinely upsetting the viewer.

Screenshot of the Atari 2600 Alien videogame.

Nonetheless, it tapped into something so potent with audiences that it became an Exorcist-style phenomenon. Over the following decades it would inspire sequels, comic books, video games, and parodies (from Mad Magazine to Spaceballs). As with Psycho (1960), its innovations – from the chestburster sequence to the fact that O’Bannon kills off the ship’s captain (Skerritt), the presumed hero of the film, well before its end – have become so familiar as to have lost some of their impact. But it’s still a potent film, one so intelligently crafted that you lose yourself in its world on each viewing. Since it’s classified as a “special effects blockbuster,” it’s easy to forget the authentic performances delivered by the cast; none of them are burdened with clumsy exposition. They have a shared history which exhibits itself in minor rivalries and resentment that largely go unspoken, but are quite clear. Small character details – Skerritt relaxing to classical music, Cartwright’s nervous chain-smoking – speak volumes; I continue to wonder if Skerritt’s Captain Dallas had a short-lived affair with Ripley, for there’s a strange mixture of shared confidence and bitterness between the two of them. You don’t get these subtle textures in your average science fiction film, and certainly not in the rip-offs which followed. One hopes that some of this will be captured in the upcoming Prometheus, Scott’s revisit to the Alien universe, but failing that, history has already proven that nothing can diminish the original.