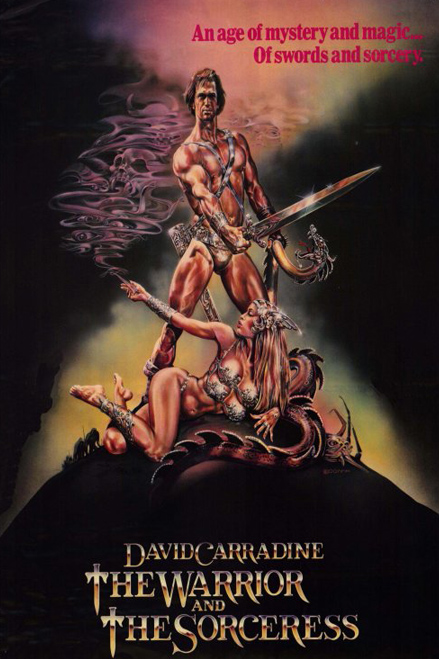

To any teenage boy growing up in the 80’s, this was “the one in the video store with the four-breasted woman on the cover.” Since this came from Roger Corman’s New Horizons Pictures, he would make damn sure there was a four-breasted woman in the movie, too; one suspects the poster, per usual, was designed before the film was made, so the pitch would be, “All we need is a four-breasted woman and David Carradine holding a sword, and we’ve got an audience.” The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984) came at the crest of a wave of sword-and-sorcery B-movies, many of them R-rated, attempting to capture both the savagery and the pulpy sensationalism of Conan the Barbarian (1982). It was a simple formula, but strangely elusive; even the official sequel to Conan felt like one of the original’s cheapie rip-offs (for that matter, this goes for last year’s remake, too). A fine cross-section of the subgenre is offered in Shout! Factory’s two-disc set Roger Corman’s Cult Classics: Sword and Sorcery Collection, which includes the prototypical Conan cash-in, Deathstalker (1983), as well as Barbarian Queen (1985), Deathstalker II: Duel of the Titans (1987), and this film, David Carradine’s magnum opus. The films typically featured Boris Vallejo poster art of oiled-up, bodybuilding cheesecake, like the cover of an 80’s Savage Sword of Conan magazine – the actors themselves never looked quite this pumped. Sets and footage from previous films could be recycled liberally, as well (Deathstalker II, for example, not only shamelessly steals footage from Deathstalker, but even, as a wink to the viewer, the “old dark castle” shot from Corman’s old Vincent Price movies). But here’s the thing: despite all the shortcuts and snake-oil, exploitation films of this era knew how to entertain. They had sets, costumes, and extras. They usually had a name actor in the lead role, to rope in viewers. They shot on film, which was an expense. Sure, the end result was variable, but on the whole they put many of today’s straight-to-Netflix-streaming B-movies to shame.

On a desert world with two suns, Zeg (Luke Askew) perpetually wars with his rival Bal Caz (Guillermo Marín) for control of the city's only well.

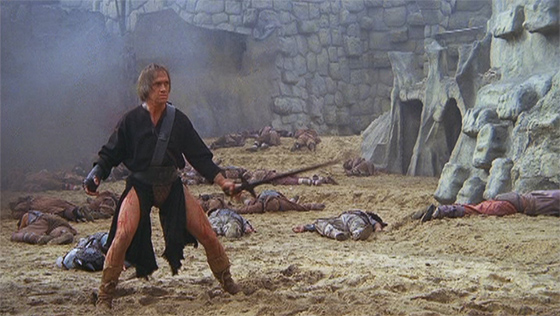

So here we have a lowbrow epic, the kind of exploitation movie we don’t often see anymore (outside of Uwe Boll, I suppose). You don’t need to look that closely to see that director John C. Broderick is maximizing his limited resources, and that effort, at least, is impressive. Shot in Argentina as an Argentinean co-production, there is one large set built for the walled city, a well in its center; this is all that’s needed for most of the sequences, since the plot centers around that well. The town square isn’t huge, so if you pack it with extras, you can convincingly create the idea of two armies warring for ownership of the well. Build a throne room for each of the two tyrants, plus a dungeon and some stone corridors, hire some extras, many of whom don’t mind nudity (which saves on wardrobe expenses), and you’ve got yourself a picture. I point this out to explain that no, The Warrior and the Sorceress is not a “good” movie, but it’s boozy fun and worth your time if you know what you’re getting into. Carradine plays Kain – that’s Kain with a “K,” and not the character he played on Kung Fu, wink-wink; often referred to as “The Dark One,” he’s a wanderer in a black robe with a sword slung to his back. Traveling through a parched, desert landscape with two suns in the sky, a la Tatooine, he arrives in a city built around one of the rare sources of water on this planet. Two factions battle for control of the well: the obese, decadent Bal Caz (Guillermo Marín), who prizes his giant pet lizard (a pathetic-looking rubber puppet), and the more ruthless Zeg (TV character actor Luke Askew), who is holding captive a sorceress, Naja (Maria Socas), and coercing her into creating an indestructible sword so that he can conquer Bal Caz once and for all. Kain, with no vested interest in a winner, decides to play both sides off one another to maximize his loot.

Maria Socas as the sorceress Naja.

If Kain’s actions sound familiar, that’s because The Warrior and the Sorceress is essentially a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s classic samurai film Yojimbo (1961). Some scenes are even directly lifted from the film, most notably a comic moment when the two armies face off in the town square, screaming and waving their swords at one another, but too frightened to act. Even Carradine dresses like a samurai, and inherits Toshirô Mifune’s swagger. Yojimbo had already been remade as A Fistful of Dollars (1964), and director Broderick extends his homage by including a soundtrack of Ennio Morricone-inspired, Spaghetti Western music (by Luis María Serra). The initial drafts of the screenplay were written by William Stout, the fantasy illustrator who created the poster for Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards (1977), and was a production artist on both Conan films; as he recounts on his website, the film was originally to be called Kain of Dark Planet, and written in the style of John Norman’s controversial, erotic Gor fantasy novels. He incorporated elements of Yojimbo, but never intended the film to be modeled so closely after Kurosawa’s film; he was dismayed to see the finished film was “unabashed plagiarism.” I would more charitably call it a remake, since the homage is so overt; as an adolescent I became aware of the film by reading about it in Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide, which described its relation to Yojimbo with the term “copycat.” (In the same blog post, Stout also recounts how he had to threaten legal action to get his name attached to the film. Corman, apparently unaware that Broderick had removed Stout’s name from the screenplay, sent him a payment taken out of Broderick’s director’s fee.)

Kain, played by David Carradine, amidst the film's climactic battle.

The film’s origins as a tribute to Gor are evident in the finished product, most notably the otherwise baffling decision to have actress Maria Socas spend the entire film wearing only a thong. (The screenshot of Socas used in this post is one of the few I could take and still keep this site safe-for-work.) The statuesque, fiery-eyed actress ostensibly plays the “sorceress” of the title, though her role is that of the stereotypical fantasy slave girl, topless, chained, and awaiting rescue by the brawny hero. She doesn’t perform any sorcery, and those allusions to her powers feel like a last-minute rewrite to justify the title, which was forced upon Broderick by Corman. Her nude scenes – so abundant as to provide a good deal of the film’s unintentional humor – are matched only by a few other memorable touches of exploitation, such as the aforementioned four-breasted dancer, or the scene in which Zeg drowns a nude woman in a glass tank while he dines with Kain. These are highlights. The lizard still looks phony, as does the rubber, tentacled monster Kain battles in a dungeon; some of the sets look like they might topple over if you pushed on them, and the dialogue is riddled with fantasy gobbledygook that is delivered in the hammiest manner possible. Though there’s some genuine swordfighting choreography here, it’s staged lethargically. So why is it that I wish there were more B-movies like this today? The Warrior and the Sorceress may be ridiculous nonsense, but at least they knew how to put on a show.