“What will become of the Baron? Surely this time there is no escape.”

-Poorly-choreographed mermaids, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen

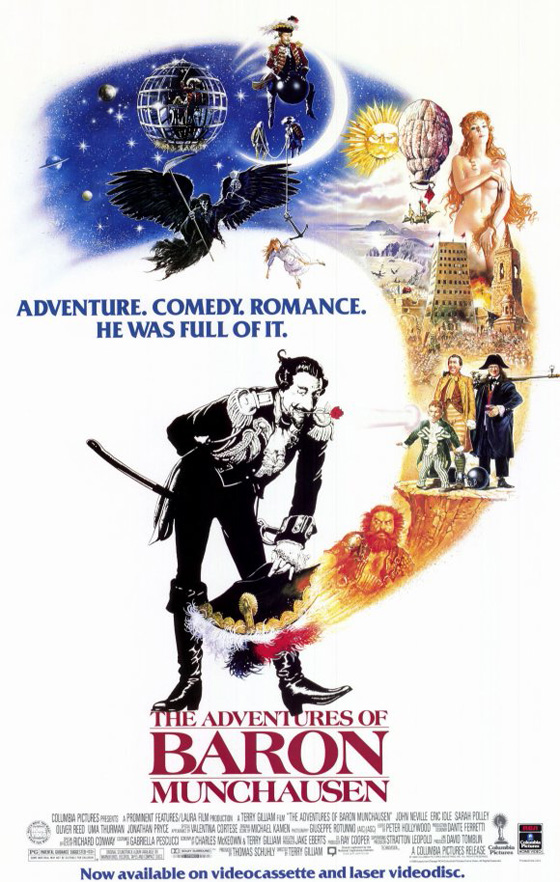

I first saw Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) when I was twelve years old. I was reading the Milwaukee Journal (the funny pages and the Movies section were all I read) and came across a review for the film. The review described flying heads on the moon, a winged Grim Reaper, a hot air balloon made of women’s underwear, a three-headed gryphon, a fish that swallowed ships, and so forth. I had never before begged my parents to take me to a movie as I begged them to take me to Baron Munchausen. Smart move, in retrospect, since it was an exclusive engagement at the Oriental Theatre downtown, and one of the few theaters in the country that was showing the film; as Gilliam explains in a documentary in the new Blu-ray special edition of the movie, Baron Munchausen didn’t even receive the standard arthouse release. I was one of the lucky few to see it on the big screen. My dad took me, and it was the first time I’d ever been to the Oriental Theatre; it was (and is) an old movie house dating back to 1927, ornately built, with a giant main theater with heavy red curtains, looking just a bit like the decrepit but grand proscenium upon which Baron Munchausen relates his tall tales. I was the right age for this film, the perfect age. The only other Gilliam film I’d seen was Time Bandits – around when that came out, too – and although I’d found that movie to be quite frightening (Gilliam made God terrifying), I was also enthralled by its fantasy, in particular the iconic image of the giant emerging from the sea wearing a galleon as a hat. Still, it’s not that I went into Baron Munchausen thinking, “Oh good, it’s the latest film from the director of Time Bandits.” I wasn’t that familiar with Monty Python. All that Gilliam/Python obsession came later, and so his view of the world – absurdist, fantastic, surrealistic, vulgar – was a wonder to me. At the ticket counter, my father said, “Two for…Baron Von Munchausen?” And, like Sally correcting her father in the film, I had to insist, “It’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen!” As the film began, right away I knew I was seeing a different kind of filmmaking – it seems less innovative now, but the mere notion that the title of the film was displayed only as the banner of a crooked flier for a play, pasted to the base of a decapitated statue, seemed really mind-blowing to me at the time. This was not going to be your standard escapist fantasy. When I saw the obese harem girls twenty minutes into the film, wading through the sultan’s pool, being led by eunuchs amidst two dozen narrow columns and a menagerie of animals – I was warped forevermore. Sex, to my twelve-year-old brain, was a subject of great curiosity, but it was also very mysterious. So it is in the film. Whatever the sultan was doing with all those obese women, I dared not imagine (nor do I still); when the body-less Queen of the Moon began making exotic moans, complaining that her body was in bed with the King, I knew that sex was involved and was panicked that the movie might visit the subject so straightforwardly (I was with my dad, you see); instead, the Baron nervously explains to young Sally that the King is just “tickling her feet,” which then proves to be the case, luckily for me. Violence, too, seemed over-the-top yet innocent, storybook; decapitations occur bloodlessly, and one severed head still manages to wink at a harem girl when he lands in her lap. Could this film be on my wavelength? No, it had trumped me: it was presenting a reality even stranger than the stories and comics I was writing in my spare time. It was opening up my imagination into a wider universe.

The harem.

I could not understand why the film, for the next several years, was referred to as a “disaster.” I understood that it went over-budget, but I didn’t see why that should affect one’s opinion of the completed film. What I’d seen was not a disaster, but, in my limited experience, one of the Greatest Films of All Time. I didn’t know this phenomenon of judging a film by its accounting books was already firmly established; I had never heard of Heaven’s Gate. The truth is that, when this phenomenon occurs, most people don’t see the finished product and indeed give it a wide berth, having already heard, from people reciting people reciting people reciting stories from Variety, that the film is a “disaster.” When it came out on video, only two copies appeared in my local video store, and they proved tremendously popular. I had to stake out the place before I finally could rent Baron Munchausen, copy it using the old VCR-to-VCR method, and study it in more detail. I watched that old pan-and-scan copy endlessly. I tracked down the soundtrack of the film, one of (the late) Michael Kamen’s best scores. I read the book Losing the Light, by Andrew Yule, which chronicled the making of the film warts-and-all, and at last understood the troubled production history. (I still recommend the book, the best ever written on the subject of Gilliam.) I won’t go into the voluminous details of those troubles, as the three-part documentary on the new disc offers a good summary. But after reading the book, I could objectively conclude that some of the problems were caused by my new hero, Gilliam, though the great majority were not. I came away with the notion that Gilliam was a bit cursed (I was beginning to familiarize myself with the history of Brazil, as well), an idea that has spread and become another popular fiction as more and more of his films have hit near-legendary snags during the production phase, most famously with his aborted project, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. That his star, Heath Ledger, died in the middle of The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009), has further given fuel to this myth, which is unjust not only to Gilliam but to the memory of Heath Ledger.

Uma Thurman's screen debut, as Venus.

But Gilliam has a bigger following in 2008 than in 1988, and it helps Munchausen‘s reputation that Gilliam drastically retreated from big-budget spectacles after the film’s financial failure: he made the acclaimed, low-budgeted drama The Fisher King (1991) next (which, contrary to Munchausen, insists on the importance of reality over fantasy), then the elegiac science fiction film 12 Monkeys (1995), and the cult classic Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), which was a small enough production that it could afford to be a theatrical flop. Because of these retreats from Munchausen‘s scope and scale, the former film looks all the more rare and beautiful. It is Gilliam at his most unrestrained, letting his fancy take him where he pleases. Well, almost: the moon sequence was drastically altered at the insistence of the studio and the creditors, reduced in scale so that a city of 2,000 became just two (Valentina Cortese and an uncredited Robin Williams); and the passage from the book that made Gilliam want to make the film in the first place had to be eliminated entirely: the Baron’s horse, bisected by a portcullis but oblivious to the fact, drinking from a fountain and letting the consumed water spill onto the ground behind it. Regardless, what made it onto the screen is so visually stunning that it doesn’t miss those scenes, which, admittedly, would have slowed down the story anyway. You still have a vast army of Turks, with elephants and siege towers, storming the city; you still have the Baron (the late John Neville) riding a cannonball through the air; you still have Eric Idle racing to Spain to fetch a bottle of wine, on feet that spin like the Road Runner’s; you still have winged, skeletal Death stalking the Baron throughout; you still have the inside of a great fish with its vast, half-eaten shipwrecks; you still have the Baron’s arrival on the Moon, one of the most serenely beautiful ever to be committed to celluloid; you still have the Baron waltzing with Venus (Uma Thurman) through the air, surrounded by waterfalls, as stop-motion cherubs drape them in a ribbon for God’s sake. It’s time to fess up: it’s one of the great, iconic fantasy films, right up there with Ray Harryhausen’s best and both Thieves of Bagdad. I’d even go further and say that it improves upon Raspe’s original book, which was a collection of charming tall tales that acted like individually separated jokes with tidy punchlines. Gilliam’s film, co-written with Charles McKeown (who also plays Adolphus), is actually about something. It has some fairly profound things to say about aging, impetuousness, responsibility, and one’s need for fantasy. It was something of a manifesto for Gilliam, and although it is often grouped with Time Bandits and Brazil as the third part of a trilogy (this, at Gilliam’s own insistence), I think it works best when compared to nothing but itself, for it’s a completely one-of-a-kind spectacle.

John Neville as the Baron.

For years Gilliam treated Baron Munchausen as the bastard child of his filmography. Perhaps the traumatic experience of making the film haunted him for a long while afterward, or perhaps he began to believe the critics who dismissed it as pretty but flawed. It’s a relief, then, to hear him embrace the film on the Blu-Ray audio commentary, recorded with McKeown. He’s come to grips with what he’s made, and has begun to appreciate that he may never make a film like it again. Most of what he imagined somehow made it onto the screen. If that’s about 75% of Gilliam’s intentions, well, at least that’s pound-for-pound more imagination, wit, and grace than most films possess.

This review originally appeared on my old blog Kill the Snark in 2009.