Goldfinger (1964) is probably my favorite James Bond film. (Look, if Sean Connery had stuck around for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, we’d be having a different conversation.) “Favorite” is the operative word here; From Russia with Love (1963) is superior in many ways, with a better all-around cast, a classic espionage plot, and a stronger aura of Ian Fleming. Goldfinger is simply fun. It’s also the moment when the James Bond series reached its apotheosis. From here on out the 007 films would get more expensive, more spectacular, more over-the-top, and, ultimately, more self-aware – they would never again be as pure, as genuine. If you were to introduce the series to a creature from another planet (for I can think of no other being who would be unaware of James Bond), you’d choose Goldfinger. The cocky chauvinism, the impish humor, the early-60’s style and sophistication, the ludicrous plot – it is the series in a bottle that goes down like fine Chianti.

Gert Frobe as Auric Goldfinger, one of James Bond's most memorable adversaries.

It is also the birth of the blockbuster, leading straight toward Thunderball (1965), with its excessive merchandising campaign. From Dr. No (1962) onward, the series was an international sensation, and the budget was bigger for each production – Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli took the dollars they earned and put them right back into each new James Bond film, calculatedly giving the audience exactly what it wanted…which meant, ultimately, that Fleming’s novels were increasingly left behind in the race toward bigger and better. You can see those points of departure creeping into Goldfinger, whose Aston Martin DB5 is considerably more gadget-equipped than the novel’s DB III. But the series had not yet lost its sense of good storytelling. This is a duel between 007 and Auric Goldfinger (Gert Fröbe) which escalates from cards to golf to a laser beam that threatens Bond’s gender. Gadgets are introduced by Q (Desmond Llewelyn) and then satisfyingly put to use, while the plot unfolds with an easy-to-grasp logic: we see how Goldfinger is smuggling his gold out of England (inside the structure of cars shipped out of the country, then stripped in a factory, the gold melted back down); we’re with Bond as he overhears the details of Operation Grandslam, a plot to rob Fort Knox; we then uncover the hidden twist in that plot, which makes sense in such an offbeat way that it puts a smile on your face. Now consider that our hero is held prisoner – helpless – for half of the story, something you would never see in other Bond films. You could argue that it makes Goldfinger less exciting, since, by necessity, that means less action. I would argue that it adds to the suspense, building toward the memorable Fort Knox showdown with Goldfinger’s henchman Oddjob (Harold Sakata), which makes a flying-hat duel a lot more thrilling than it ought to be.

Jill Masterson (Shirley Eaton) helps Goldfinger cheat at cards.

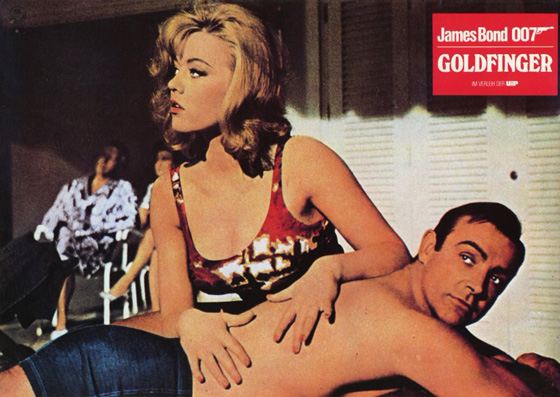

Guy Hamilton takes over directing duties for Terence Young, and – surprisingly – you don’t really miss the gifted Young. How can you complain, when you have one memorable image after another, such as the aforementioned laser beam (“No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!”); or Shirley Eaton, with binoculars, lounging in a black brassiere and panties, one foot lazily hanging in the air; or the innocuous-looking old lady guarding the gate of the factory, who grits her teeth and opens fire at Bond with an oversized machine gun; or – my favorite – a bar of Nazi gold thumping onto a putting green, and sending Goldfinger’s putt awry with its weight. I could go on: Bond’s formidable Aston Martin foiled by a simple mirror; the classical statue decapitated by Oddjob’s bowler hat; the debut of Q’s gadget shop (“I never joke about my work, 007”); the introduction of Honor Blackman’s Pussy Galore (“I must be dreaming!”). After a memorable stop at Dr. Strangelove (1964), production designer Ken Adam is back with a bang – note that even a minor, briefly-glimpsed location in the pre-credits sequence (the room where Bond sets his explosive) is gorgeously designed. His idea of Fort Knox’s interior is so permanently embedded in my cinematic imagination that I feel it must be a factual representation, even though I know it to be highly improbable. The judo-skilled Pussy Galore, significantly, is the first Bond girl to be just as tough as 007, though inevitably she succumbs to his rape-y advances. In the novel, Galore – a minor character – is a lesbian; the fact that Bond conquers her homosexuality is just one of the dated and uncomfortable aspects of the book (Fleming’s anti-Korean racism being even more distracting). Ironic that a character so firmly rooted in a particular era and mindset has managed to effortlessly endure: even in the film adaptation, Bond is casually slapping the behind of Dink, his big-breasted blonde masseuse, and – perhaps the biggest cultural crime of all – dissing those young, long-haired upstarts The Beatles.

Bond ruins Goldfinger's shot.

Yet, in this Mad Men era, these dated aspects only add to Goldfinger‘s camp appeal – just like the can’t-get-it-out-of-your-head theme song, sung to the hilt by Shirley Bassey, and fully integrated by John Barry into his superb score. This is a film in which a poolside scene is overcrowded with extras, the vast majority of whom are beautiful, bikini-clad young women. To say that this is a white male’s fantasy is pointless; of course it is, but in the eye-poppingly colorful, playfully exaggerated world of Goldfinger, it’s nothing less than dazzling pop art. No other Bond adaptations were necessary, but of course we got a multitude, evolving to reflect every decade’s sensibilities; and most of the 1960’s Bond parodies used Goldfinger as the key reference point. I could simply dwell here, though: lingering by the pool, sipping my martini, waiting for Felix Leiter, a mission, and a masseuse.