He signed his work “Moebius.” His name was Jean Henri Gaston Giraud, born in Paris in 1938, a fashion illustrator who turned to comic strips to let his vast imagination loose – and swiftly became one of the most acclaimed illustrators in Europe, creating Blueberry, The Incal and Madwoman of the Sacred Heart (both with cult director Alejandro Jodorowsky), Arzach, The Airtight Garage, and many, many others; he was also an in-demand concept artist for feature films, helping design the worlds of Alien, Tron, and The Abyss. Sadly, he passed away on March 10 at age 73, but he left behind a seemingly bottomless well of works and a lasting influence on visual artists, authors, and filmmakers. Open a book of his to any page and you’ll see why. His art was uncluttered, modern, and never hid behind gimmicks. His lines were simple, but elegant and suggestive. His color was eye-popping. He didn’t shy from the cartoonish, yet his work was never less than tactile: erotic, scatological, effortlessly realistic; a panel later he could be ethereal, metaphysical. Metal Hurlant, the illustrated magazine he founded with Philippe Druillet, Jean-Pierre Dionnet, and Bernard Farkas, helped propel his stardom in the graphic arts world, and – though it was an anthology – it was Moebius’s art with which the magazine became most closely identified; when it was translated into English in its latecomer American counterpart Heavy Metal, the letter pages were filled with tongue-tied adoration for the French artist, and collections of his work began to finally appear on these shores (though most are now out of print).

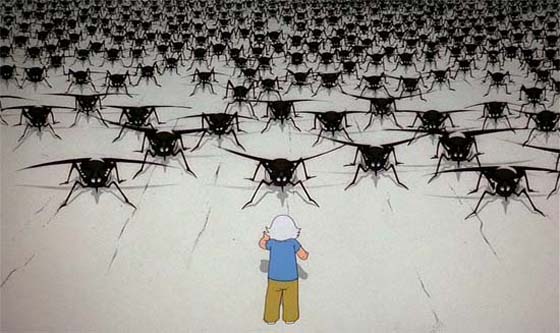

The Xuls of the planet Gamma 10, absorbing and conforming victims into their collective, soulless intelligence.

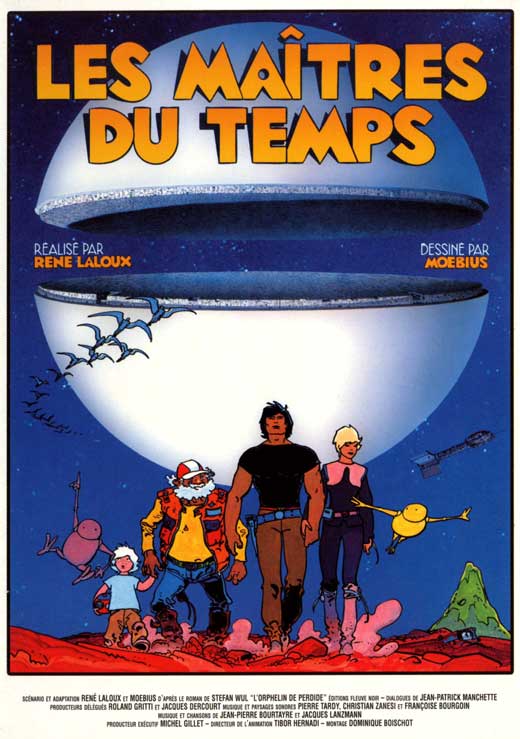

Meanwhile, at his home base in France, Moebius formed a partnership with the director of Fantastic Planet (La Planète sauvage, 1973), René Laloux. They intended to launch a series of one-hour animated specials for French television, each adapted from a science fiction novel by Stefan Wul, the author of Oms en série (the novel which inspired Fantastic Planet). The first would be L’orphelin de Perdide (The Orphan of Perdide), designed and storyboarded by Moebius and animated by Laloux’s fledgling studio. Ambitions grew for the project, and it was quickly determined that the production should be expanded into a feature-length film, now retitled Les Maîtres du temps (Time Masters). Animation was shifted to a studio in Hungary to accommodate the workload, and both Laloux and Moebius concluded in later years that this move ultimately led the production astray – the quality of the output became inconsistent. They would be dissatisfied by the final product, which was the victim of an inadequate budget and (Moebius’s accusation) a few inexperienced animators, who rendered some the film’s central characters too crudely. But at least the film was completed and released. Although Laloux would go on to another science fiction epic, 1988’s Gandahar (released in a butchered form in America as Light Years) – completing a trilogy of sorts – Moebius wouldn’t have much luck in the animation industry. Proposed adaptations of The Incal and Arzach went unfinished, though jaw-dropping clips of the projects are available on YouTube. (Arzach was ultimately adapted into an animated series in 2004.)

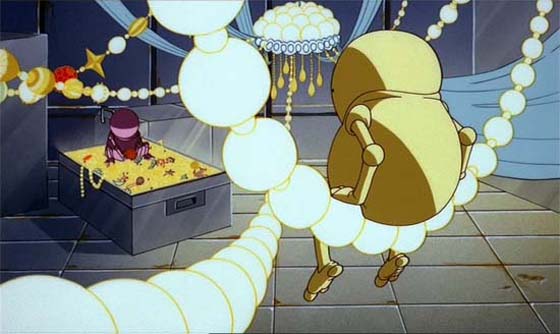

Yula and Jad, the telepathic gnomes of Devil's Ball, decorate their cabin with stolen treasure.

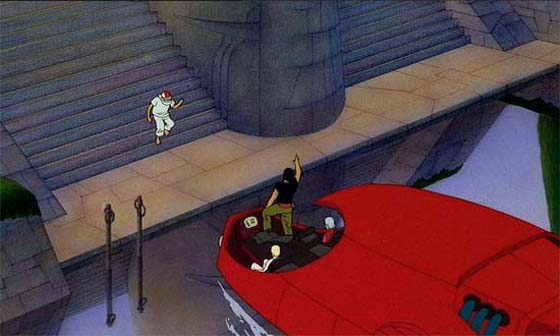

Time Masters is about a young child, Piel, who is orphaned on the planet Perdide after a swarm of alien hornets attacks his parents (which happens off-screen); as his father, Claude, is dying, he uses an egg-shaped communication device to send an emergency transmission to his friend Jaffar. Then he commands his son to take the microphone – which Piel calls “Mike” – and travel across the alien landscape until he finds a region called the Dolongs, where Jaffar can meet up with him. But Jaffar is very, very far away, escorting Prince Matton and Princess Belle toward Aldebaran; the greedy, cold-hearted prince is essentially a fugitive, having stolen the royal treasure of the planet Atral. When Jaffar receives Claude’s message, he redirects his ship’s course toward Perdide, much to the prince’s anger. So while Piel faces dangers from the flora and fauna of Perdide, guided by his companion “Mike,” Jaffar and his crew encounter obstacles of their own, including intergalactic policemen and faceless, winged drones controlled by a single fascistic consciousness. (There’s also the problem of the prince, who at one point uses “Mike” to place Piel’s life in danger.) Jaffar’s unlikely allies include a ukelele-playing old man named Silbad, a gang of space pirates, and two telepathic “gnomes” named Yula and Jad. The Time Masters of the title are introduced in the film’s climax, and their reality-twisting plans for Perdide turn this Moebius-designed film into a genuine Moebius strip.

Silbad welcomes Jaffar and his friends to the planet called Devil's Ball.

Laloux and Moebius may have expressed disappointment with the completed film, but here’s the thing: I won’t hesitate in naming Les Maîtres du temps as one of my favorite animated films. I mean, Moebius was right when he complained that the character animation was inconsistent (the gnome animation is Disney-worthy, while Jaffar, Belle, and Matton are gracelessly handled), and the ending, perhaps hampered by the small budget and limited resources, feels too abrupt. But sometimes the heart won’t listen to the head. Time Masters may be flawed, but it has so much going for it that I find it irresistible. The scenes with Piel on Perdide, talking to “Mike” and naively interacting with the planet’s wildlife, are exquisitely done, both in translating Moebius’s style faithfully to the screen and maintaining a delicate tone of awe, ominous danger, and childhood innocence. Both Perdide and Devil’s Ball (Silbad’s home) express Laloux’s fascination with xenobiology, making this film of a piece with Fantastic Planet and Gandahar; like those films, he doesn’t mind stalling the narrative with lingering shots of alien forests and lakes, and he tops himself here with giant lotus flowers that eject telepathic space-gnomes into the air, like humanoid pollen (they scream with the voice of children, “Close your minds! We’re here!”). Those two stowaway gnomes, Yula and Jad, are the heart and soul of Time Masters. They act as the film’s chorus, commenting on the action by detecting the thoughts of the crew (Prince Matton’s thoughts “smell terrible”), and are given the film’s most inspired dialogue and animation.

The domain of the Time Masters, as revealed in the film's close.

I’m also fascinated with the way the film even-handedly trades between childrens’ entertainment and intellectual, adult science fiction, with no apologies for depicting death and violence straightforwardly – for, in Laloux’s animated worlds, these are essential components to the cycle of life. Memorably, Piel encounters an ambling, four-legged, friendly beast with a short, cylinder-shaped trunk, who lets the boy ride on its back through the jungle; a few scenes later, Piel urges the cute, cartoony creature to take shelter in a cave, where it’s brutally strangled to death by a barely-glimpsed, black-tentacled beast. Piel drops his microphone and runs, and Laloux gives us a creepy shot of the device abandoned next to a stripped skull. Therefore, when Piel confronts a swarm of deadly hornets at the shore of a lake, the danger feels all the more immediate; indeed, the insects pile on top of the poor child, pecking at his skull, tearing at his clothes, bloodying him up. So give the film credit for being uncompromising, which places it in a similar orbit with Metal Hurlant (Jean-Pierre Dionnet helped initiate the project) and other French SF comics and art of the period. Most importantly, this is the rare chance to see what Moebius’s art looks like on the big screen. In its best moments, Time Masters speaks as much to the artist’s skills as to his formidable imagination and heart; and reminds us of why we’ll miss him.