One likes to imagine that after François Truffaut sat down with Alfred Hitchcock for the extended interview sessions that became the seminal book Hitchcock by Truffaut, he became restless to try out some of Hitchcock’s theories on his own. The result, then, would be The Bride Wore Black (1968), and certainly no one missed the overt homage. Truffaut’s film is a love letter to Hitchcock in many ways: he brought back his Fahrenheit 451 composer, Bernard Herrmann, whose most famous work was for Hitchcock (The Man Who Knew Too Much, North by Northwest, Vertigo, Psycho, etc.); for his story he chose a novel by Cornell Woolrich, whose fiction had inspired Rear Window; and the plot would involve a series of elaborate murders by an icy woman (not a blonde, alas), all executed with straight-faced black humor. Reportedly, Hitchcock was delighted with the result. (He was a cool cat. He also admired Russ Meyer’s Supervixens.) In later years, many critics would take Brian de Palma to task for imitating the master so closely; but the greatest success of The Bride Wore Black is that it adopts Hitch’s theories of suspense filmmaking without quite imitating him. It is still recognizably a film by Truffaut, one of the greatest directors of the Nouvelle Vague.

The tragic wedding day of Julie Kohler (Jeanne Moreau) is only revealed gradually, in impressionistic flashbacks spurred by the confessions of dying men.

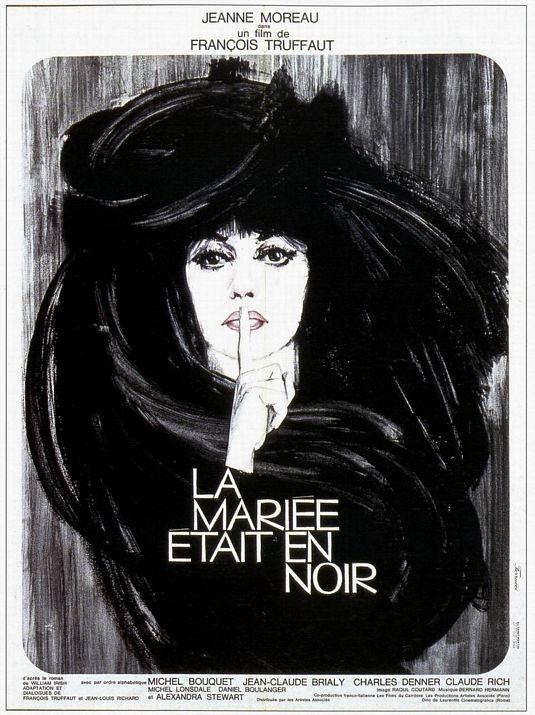

Truffaut’s Jules and Jim star, Jeanne Moreau, was nearly 40 when she was hired as the lead of The Bride Wore Black. Hitchcock may have hired someone younger, but Truffaut wanted to create a showcase for Moreau, who was his ex-lover and one of the greatest stars of European cinema of the 50’s and 60’s. And her age adds an invaluable layer to the story. She is playing Julie Kohler, a woman whose husband was murdered many years ago on the steps of their wedding chapel. She has spent an untold amount of time pursuing the men responsible for that single, fateful gunshot out of the blue – her features reveal that she’s haunted and just a little bit weary, but also intelligent, emotionally reserved, and calculating. Truffaut gave her some private motivation, which he confessed to Hitchcock, and is suggested in the film only by an easily-missed line of dialogue: Julie is likely still a virgin. This contributes to her awkwardness when a member of the opposite sex (usually her intended prey) makes a pass at her: an uncomfortable vulnerability which only makes the performance more intriguing to watch as she goes about her plans of revenge. The viewer is given to wonder if she might let down her guard and see her victims as human beings; and even, possibly, allow herself to fall in love – when one of the men she means to kill, a talented painter named Fergus (Charles Denner), becomes enraptured by her beauty. He casts her as Diana the huntress, giving her a toga and a bow and arrow while he sketches her image, and paints a nude of her on the wall next to his bed. Julie seems to become confused, possibly even touched. But when the artist suggests she turn her arrow more in his direction, she doesn’t hesitate to aim it straight at his heart.

Julie exchanges rings with her murdered husband.

What makes The Bride Wore Black such a joy to watch is the manner in which it rewards the viewer’s attention. The unconventional opening credits, set to Herrmann’s score (mixing the traditional wedding march with an unsettling suspense theme), is one fixed camera shot: a photo of a topless Jeanne Moreau being rapidly printed, over and over, into a growing pile of nudes. You’re inclined to think it’s just fodder for a smut shop; it might take a second viewing to realize it was actually Fergus’s bedside painting of Moreau being reproduced for a wanted poster, being the only image available of the killer’s face. It’s almost a surrealistic gesture to place this scene out of context; and you could say the same for Truffaut’s never explaining exactly how Julie Kohler discovers who was responsible for her husband’s death. (It’s certainly extraordinary detective work on her part, and to leave out that exposition allows Truffaut a touch of Nouvelle Vague experimentation, as well as to let the narrative just cut to the chase.) After the first murder – and once the viewer realizes this isn’t a whodunit but a whenwillshedoit – Truffaut begins to tease the audience’s expectations as he moves from one potential murder scene to the next. Moreau’s scheme to off Michel Lonsdale’s smarmy politician Rene is especially fun: a game of three players – Julie, Rene, and Rene’s young son – in which our film’s antihero, pretending to be the son’s teacher, tries to negotiate the restless child into bed, and then gradually steer the father into a perfectly helpless position. Watch the entire sequence carefully and you’ll see Truffaut’s modus operandi for The Bride Wore Black: it’s as much a comedy on human behavior as it is a satisfying black-widow thriller, and the film triumphs on both counts.