In today’s world of globalization and internet file-sharing, you couldn’t really get away with what American International Pictures was doing in the mid-60’s: cutting up Russian special effects epics, inserting new American footage with different plotlines, and releasing them under titles aimed at drive-in exploitation. The visually stunning Russian originals were essentially inaccessible to Americans; to salvage them for scrap parts was deemed acceptable. Among these were Battle Beyond the Sun (1963, spliced together by Francis Ford Coppola at the behest of Roger Corman) and Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965). The latter was assembled by Curtis Harrington, who had directed the remarkable, Val Lewton-esque Night Tide (1961), as well as some experimental films; Harrington was a friend of avant-garde filmmaker Maya Deren and a former collaborator with the mad genius Kenneth Anger (who, after a falling-out, issued a Satanic curse on Harrington). He was fascinated by the occult and Gothic romanticism – Poe was a favorite, and his last film was an adaptation of “The Fall of the House of Usher” – but he had to find work as a filmmaker, and so he found his way to working under a fellow Poe fan, Corman, at AIP in the 60’s. After Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet, for which he used the pseudonym of John Sebastian (after Bach, and not the Lovin’ Spoonful frontman), Harrington was tasked with repurposing footage from the Russian films Nebo Zovyot (1960) and Mechte Navstrechu (1963). The films were essentially propaganda for the Russian space program, but Cold War be damned, Corman needed their budgets for his own B-movie epics. Never mind that the letters “CCCP” on the side of a spaceship might creep into a shot here or there.

"Queen of Blood" is front-loaded with visually arresting footage from the Russian films "Nebo Zovyot" and "Mechte Navstrechu."

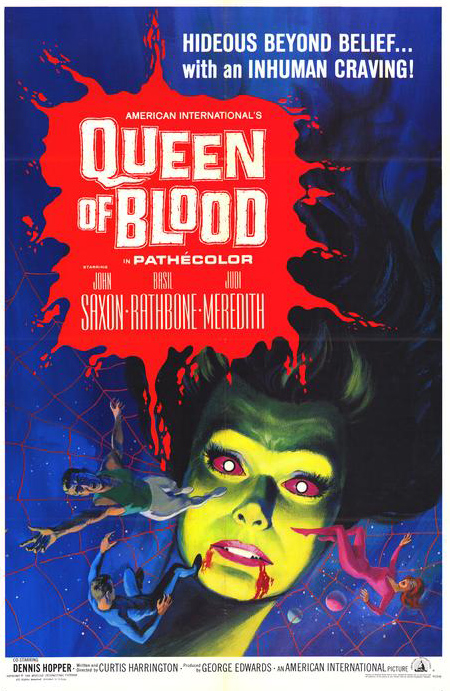

Harrington’s answer to this challenge was Queen of Blood (1966). The source films dealt with a journey to Mars and contact with an alien race, and so does the American version, though eventually Harrington sidelines the plot into AIP territory with a space vampire feeding on a crew of too-trusting astronauts. Most of the borrowed footage unspools in the first half of the film, which presents a curious problem. For one thing, these shots are visually spectacular, with bright colors, impressive model work, and inventive optical effects that are borderline-surreal (all this is par for the course for Russian fantasy filmmaking of the 50’s and 60’s). On the other hand, to string them together, Harrington relies upon the dry procedural approach that typified American space exploration films of the 50’s, such as Destination Moon (1950), Rocketship X-M (1950), and Project Moonbase (1953). So you can be dazzled by the effects and either amused or bored by the bland characters and techno-babble dialogue. It helps that the casting is interesting, with Basil Rathbone as a brilliant but callous scientist, John Saxon as the square-jawed captain, and Dennis Hopper – a friend of Harrington’s, and star of Night Tide – as one of the more sensitive crew members. They may not have much to work with in the film’s first half, but at least, as a viewer, you can pass the time by playing the “Oh, look, it’s…” game. There’s even a significant cameo by Famous Monsters publisher and genre legend Forrest J. Ackerman, playing Rathbone’s assistant.

Paul Grant (Dennis Hopper) offers some liquid sustenance to their alien passenger (Florence Marly), though it's not the type she's seeking.

After a few eerie, dreamlike (and somewhat disjointed) scenes in which the crew explores a derelict alien ship on a Martian moon, recovering an extraterrestrial survivor (Florence Marly), the plot proper finally kicks in. They’re surprised to find that the alien is humanoid, although the mute creature may have more in common with vegetable than animal: she has green skin and silver hair shaped like the bud of a flower (“Her skin…appears to have a high chlorophyll content,” comments one crew member, making the most of some very cheap makeup). She also seems to have telepathic powers. She mesmerizes the male crew into silent gaping when they first examine her, though the sole female astronaut, played by Judi Meredith (Jack the Giant Killer), is unmoved. At night, the alien uses her powers – including glowing eyes – to hypnotize her victims before drinking their blood, an almost sexual seduction that seems to be inspired by Hammer’s Dracula. John Saxon joins Meredith in distrusting the creature, but even he lowers his guard, and Meredith discovers his half-conscious body lying on the floor while the alien “queen” sucks blood from a gaping wound in his wrist.

Forrest J. Ackerman cameos in "Queen of Blood," admiring a collection of the Queen's pulsating, slime-covered eggs.

There’s a genuine anticlimax when it’s discovered that the Queen of Blood can be slain by simply scratching her; the creature, which Saxon diagnoses as a hemophiliac, subsequently bleeds to death. Has there ever been an easier way to defeat an alien menace? Nonetheless, when Saxon discovers that the alien has been laying eggs in every single compartment in the ship (she’s been very busy while the crew slept, apparently), he dreads an alien invasion and suggests exterminating all of them. Only with great reluctance does he decide to submit to Meredith’s suggestion, and leave the specimens intact for Rathbone’s scientists to study. Harrington’s script hits all the expected tropes, but the final shot adds a touch of welcome humor – an assurance that the film is not to be taken that seriously. These days, Queen of Blood might be of greatest interest for genre fans as a predecessor to Ridley Scott’s Alien (although it more closely anticipates Tobe Hooper’s outrageous space vampire epic Lifeforce, in truth). It bears much in common with It! The Terror From Beyond Space (1958) and especially Mario Bava’s terrific Planet of the Vampires (1965), a film Harrington hadn’t seen. But Queen stands on its own as one of the strangest mash-ups the AIP exploitation factory produced in the 60’s.