“I haven’t beaten you since you were a little girl – have I, Alice?”

So murmurs William Hargood, a church-going, highly-respected figurehead of the community – while he confronts his daughter in her darkened bedroom, stumbling toward her with a mean-looking hunting whip in his hand. Drunk, unsteady on his feet, his eyes dip toward her breasts in the middle of his slurred sentence. “If you touch me, father, I’ll never forgive you,” she says, but he grabs hold. She wriggles out of his sweaty hands and escapes out the window. He begins to chant, “I’ll whip you, Alice,” over and over, chasing her out of the house and through the garden, where he suddenly encounters Alice’s new friend. He’s tall, with hellfire in his eyes; has a black cape with red lining. The man seems to have had a transformative effect on Hargood’s daughter. “Now,” says the stranger, and Alice, smiling, strikes her father hard in the head with a shovel; he collapses and lies still, blood oozing from his brow. Clearly, this was not your typical Hammer film, nor your typical monster movie.

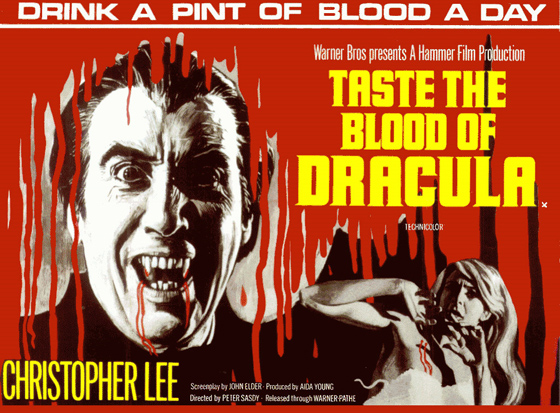

Christopher Lee, reincarnated (against his will) as Dracula.

But you would have figured that out by now, for the hour leading up to this murder has been just as unusual. This is partly a result of its troublesome birth. Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970) was the fifth film in Hammer’s successful Dracula franchise, kicked off, of course, by the classic Horror of Dracula (aka Dracula, 1958), which, along with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), launched Hammer Horror and established Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing as genre icons. But Taste the Blood was only the fourth film to feature Lee, since Cushing embarked on a solo Van Helsing adventure in the superb sequel Brides of Dracula (1960); it was eight years from the first film before Lee was convinced to don the cape (and trademark signet ring) again. He was doing his best to avoid typecasting: in the intervening years he’d played the Mummy, Sherlock Holmes, Fu Manchu, pirate captains, even the Devil. After playing Dracula two more times for Hammer, he felt enough was enough. A script was prepared which would go the Brides of Dracula route – with a younger vampire, a fresh face. That would be Ralph Bates, already being prepped as the new Hammer Horror star; he was quickly slated for major roles in Horror of Frankenstein (1970), Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde (1971), and Lust for a Vampire (1971). According to Marcus Hearn and Alan Barnes in their illustrated history of the studio, The Hammer Story, Warner Bros. protested they had bought the film on the condition of Lee’s name on the poster. Producer Aida Young returned to Lee and sweet-talked him into returning for just one more Dracula picture. He’d make three more after that.

Peter Sallis, John Carson, Geoffrey Keen, Ralph Bates, and Roy Kinnear inspect the remains of Dracula.

That’s not including Count Dracula (1970), his film for Jess Franco which he ran to willingly on the promise that it would be a more faithful adaptation of Stoker’s novel (which Lee adored). Released the same year as Taste the Blood of Dracula, the Franco film by comparison seems – well, bloodless. Taste is the last great Dracula film from Hammer, and Lee was right about one thing: it ought to have been the last. It’s richly designed, with an intelligent script and one of James Bernard’s most lushly romantic scores. Despite its somewhat anticlimactic finale, I’d rather the series have ended here than in the micro-budgeted, lackluster films that followed (I confess, I do enjoy the comic book silliness of The Satanic Rites of Dracula). Director Peter Sasdy was a television director here making an impressive big-screen debut; Hammer recognized his potential, and would bring him back for Countess Dracula and Hands of the Ripper (both 1971). If you missed the opening credits, you’d be forgiven for thinking Terence Fisher was at the helm. Consider Sasdy’s assignment. The quickly rewritten script by Anthony Hinds (under his Hammer pseudonym of John Elder) still features Bates’ character, but goes to such lengths to justify transforming him into Lee’s Dracula that the Count doesn’t make his first appearance until about halfway through the film. That this works to the film’s advantage is something of an achievement. Dracula is not the main character here, nor is he the most interesting. So the story is forced to contort itself away from the familiar and clichéd and into something new.

Linda Hayden as Alice Hargood, holding the stake while her friend Lucy - now a vampire - hammers it into the chest of her father.

One of the appealing facets of the series is that nearly each film picks up where the last left off, even if Dracula’s castle might move from one country to another, even if his resurrection might become increasingly unlikely or absurd – the continuity is dream-like. Here the familiar character actor Roy Kinnear (Help!, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory) is a traveling salesman/charlatan named Weller who becomes lost in the woods, where he encounters footage from the previous Dracula Has Risen from the Grave: Lee impaled by a cross, tears of blood running down his face, his body gradually disintegrating (again). The camera zooms into the blood for the opening titles – but then Sasdy abruptly changes the tone, shifting to some beaming families leaving church on a Sunday morning. Bernard’s music obliges, almost swooning over the scene before, just as the credits end and the Hargoods arrive back home, the sinister notes of Dracula’s signature theme intrude to darken the mood. But here the darkness comes in the form of Alice’s father (Geoffrey Keen, of Born Free and several James Bond films), whose upstanding exterior crumbles inside the home to reveal a sadistic tyrant. He immediately berates Alice (Linda Hayden) for flirting with her love Paul (Anthony Higgins): “He’s still a young man and you’re a young woman – a sexually mature young woman – and I will not have you displaying yourself in that provocative manner.” He calls her a harlot and banishes her to her room. Never mind that her collar is buttoned practically to her chin. The pall of domestic abuse hangs over Taste the Blood, a subtext the film embraces when finally William Hargood nearly rapes his daughter, and she, under the spell of the resurrected Count, retaliates and kills him. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. When Hargood’s wife (Gwen Watford) offers to make dinner, she’s batted away by William when he reminders her that it’s the last Sunday of the month – the time he’s set aside for “charity work in the East End.” What this really means is carousing at a brothel with his friends Jonathon Secker (John Carson, The Plague of the Zombies) and Samuel Paxton (Peter Sallis, later the voice of Wallace in the “Wallace and Gromit” films). The hypocrites three are eager to find the latest taboo sensation – and decide that evening to dine with the intriguing young Satanist Lord Courtley (Bates) for inspiration. And Courtley has just the thing.

Alice recoils from her drunken father, who prepares to beat her with a hunting-whip.

Lord Courtley has ambitions to resurrect Count Dracula by purchasing his last remains (a clasp, a signet ring, a cape, and a vial of blood which has turned to powder) from the merchant, Weller. A ritual in an abandoned church in which the three are urged by Courtley to go ahead and taste the blood of Dracula results in some supernatural happenings that spook the occult pretenders; in a panic, they attack Courtley, and as a group they beat him to death. After they flee the crime scene, Dracula reincarnates through Courtley’s body in a not-quite-convincing special effect. Ralph Bates has become Christopher Lee. (Not bad, but practice makes perfect: in Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde, he becomes Martine Beswick.) Seeking revenge for Courtley’s death – I’m not quite sure why – Dracula begins hunting down Hargood, Secker, and Paxton. The twist: he’ll destroy them through their children. After mesmerizing Alice into killing her father, he turns her friend Lucy Secker (Isla Blair) into a vampire. The two girls lure Lucy’s father Samuel back to the church, where, in a reversal of the Hammer formula, the vampire drives a stake through its victim (Alice holds the stake still while Lucy brings down the hammer). But just as the children prove to be the downfall of their authoritarian, deceitful fathers, they’re also capable of fighting back against the Count – it’s Alice and Paul who save the day, their love defeating Dracula’s corruption. So the story has a counterculture message: youth will overcome.

"You're free, Alice, free to choose good or evil!" Paul (Anthony Higgins) breaks Dracula's spell over Alice.

Filmed in 1969 and released in the spring of 1970, Taste the Blood of Dracula is something of a transitional film for Hammer. It still resembles the thoughtful Gothic romances of Terence Fisher which typified the studio’s late 50’s and early 60’s output, but it also takes strides toward the more risqué vampire films in the studio’s immediate future: The Vampire Lovers (1970) would be released in mere months, and offer a new commercially successful model to follow. Without being fully committed to sensationalism, Taste the Blood can apply its exploitation elements with…well, taste. Hayden, who had just starred in the controversial Baby Love (1968) as an underage sexpot destroying her adopted home, here plays an innocent whose sexuality – that which her father dreads, but guiltily yearns for – is let loose by Dracula. Soon both she and Lucy are sporting the requisite Hammer cleavage as they lure their victims with saucy smiles. Nudity would soon become a requirement as well, but the film only uses it where it makes logical sense: prostitutes glimpsed in the brothel. It sharpens the contrast between the two worlds which the three old men inhabit: the church (we see them leaving down the path with Bibles clutched to their chests) and the whorehouse, where they watch a lewd performance of an Eve and her snake. But most welcome of all is the wit of Anthony Hinds’ script, on display from its opening pre-credits sequence (with a wonderful Kinnear) to the almost elegant manner in which it undermines the viewer’s expectations, beginning with the simple idea of turning its heroine into a killer, and allowing the audience to root for Dracula, for once. Sadly, Hinds would part from Hammer within the month. Gray skies were ahead for the once-innovative horror studio, and new, more shocking films were hitting the market. But Taste the Blood of Dracula proves that Hammer, too, could think outside the coffin.