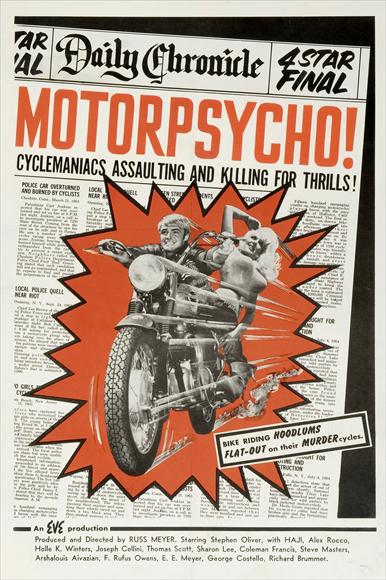

With Lorna (1964) and Mudhoney (1965), Russ Meyer finally graduated from his cheap but colorful “nudie-cuties” to feature-length narratives, and drive-in screens would never be the same again. His preference was lurid melodrama with hyperbolic scripts (he had his name removed from 1964’s Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure – he was a hired hand, and it wasn’t his idea of a Russ Meyer Film). For subtlety, he’d little interest. His stars – with bodies as if carved from the cliffs – deserved dialogue that could only be delivered by shouting. He wanted to see his men and women clash with all the grandeur of a classical myth, albeit one retold as a steamy paperback. His women weren’t shrinking violets, but sexually-insatiable she-devils, despising the men who pretended to keep them, shriveling their egos with withering one-liners. The apotheosis of this style is the notorious Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1966), but often overlooked is Motorpsycho (1965), the film which bridged that gap to psychotronic bliss. With Motorpsycho, Russ Meyer let loose on the big screen one of the supervixens he’d encountered at a strip club in San Fernando Valley. Her name was Haji (real name: Barbarella Catton). She was from Québec, though on the screen she seems to have emerged from some misty, arcane portal. You can’t take your eyes off her; and she screams her overripe dialogue like nobody’s business. No wonder that Meyer considered her for the lead role in Pussycat (plans altered when he met the even more inexplicable Tura Satana).

Animal vet Corey Maddox (Alex Rocco) forms a bond with the wild Ruby Bonner (Haji) while battling a sadistic biker gang.

A pre-credits sequence doesn’t have much to do with the plot, but throws you – with a literal splash – into the world of Russ Meyer. A middle-aged fisherman bends over his line while deliberately ignoring his absurdly voluptuous young wife (Arshalouis Aivazian). She jumps into the water, forcing her bikini-clad body into his line of vision, scattering the fish, and laughing with a tease that has a strange touch of the sadistic: “You’ve got the best there is on your line right now!” she tells him, but of course these Russ Meyer men just never understand. The title crashes onto the screen, accompanied by a surf-music instrumental that will become the main theme of the villainous “motorpsycho” gang (tellingly, the opening credits categorize its cast by “The Women” and, less significantly, “The Men”). The three Wild Ones – Peter Fonda-lookin’ leader Brahmin (Steve Oliver), and cronies Dante (Joseph Cellini) and Slick (Thomas Scott) – motor from one sexual assault to another, first laying waste to the pre-credits couple, then interfering with the lives of straight-laced veterinarian Casey Maddox (Alex Rocco of The Godfather) and his wife Gail (Holle K. Winters). While Casey is away from home doing his level best to resist the buxom temptations of a cowgirl, the gang, seeking revenge for a slight, finds Casey’s home and rapes and beats his wife. He gets no sympathy from the misogynistic sheriff (Russ Meyer, in a cameo), who shrugs off the violent assault with the eyebrow-raising line, “She’ll be okay in a week or so; after all, nothin’ happened to her that a woman ain’t built for.”

Russ Meyer has a cameo as the unhelpful, woman-hating arm of the law.

The enraged Casey takes to the road on the hunt for the gang, and arrives just in time to save their latest victim – Ruby Bonner (Haji), grazed on the brow by a bullet fired by the gang just after they murdered her tubby, grizzled husband, played by bad-movie auteur Coleman Francis. (Is every woman in town a mail-order bride?) Memorably, she’s introduced by shouting at her mate, “I need you like a hole in the head!”- which seems prescient. Ruby is a real Wild Thing, and it takes an experienced vet like Corey Maddox to handle the likes of her. United in the middle of the desert, they fend off the trio of psychopaths while also enduring the inhospitable night, and a deadly rattler. The latter leads to the film’s most memorable scene, one which Meyer would repeat like a Greatest Hits track in Supervixens (1975): frantic over the snake poison, Rocco forces the startled Haji to suck it out, leading to an orgasmic conclusion: Rocco slumping to the dirt in exhaustion, and Haji spitting the black poison at the camera, which Meyer – in a giddy little edit – parallels with one of the bikers spitting out some canteen water. You can see that this over-the-top, dirty joke of a sequence flashes like a lightbulb over Meyer’s head: so here’s what a Russ Meyer Film could be. Not mere trash: glorious trash. This snakebite would prove a point of no return in his filmography.

Mind you, there was room for improvement. The film suffers some pacing issues in its second half, as Meyer contents himself with endless shots of the bikers meandering through the desert, and the film seems to be biding its time until a final, dynamite-driven showdown (again, a device again recycled in Supervixens, to greater effect). Screenwriter W.E. Sprague, collaborating with Meyer, can’t quite match the absurdity that Jack Moran would bring to Pussycat. But Meyer injects a pulpy intensity into this little exploitation film. Everything is heightened and exaggerated beyond standard B-movie proportions, and I’m not just talking about the bust-lines. Without resorting to nudity – he wanted this film to have a wider circulation – he keeps his actresses in a state of near-undress, with Haji in particular losing her clothing piece by piece as the film progresses, until she’s lying half-conscious in a shallow gully with Rocco, her arm draped over her abundant toplessness, while he struggles to light a stick of dynamite. Eyes hidden under fearsome false eyelashes, lips often sculpted into a sneer, Haji dominates the film like a dust-devil of the desert wastes. As for Alex Rocco, who would move on to the more lucrative acting career, Motorpsycho offers him a rare starring role and a chance to essay the square-jawed, gravelly-voiced manly-man who would be played, in later films, by Charles Napier. So here you have Russ Meyer directing a biker-gang thriller with Haji, Alex Rocco, guitar music, sex, and violence. It may not have Tura Satana, but you’ll get your kicks.