Now we can look back and see that Yellow Submarine (1968) is as much an iconic work of 1960’s pop art as Andy Warhol’s soup cans. (Not that it can be so easily categorized; not that there’s been anything else like it before or since.) But it was something of a rush job. The film was intended to fulfill the Beatles’ three-picture deal with United Artists, following the phenomenal successes of A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965), pictures which helped prove that the band wasn’t just a passing (fab) fad. 1966 passed with no Beatles movie, and the exhausted band retired from touring by the end of the summer, focusing instead on their increasingly ambitious albums. In 1967, rather than handing their identities over to the comic inventions of Richard Lester, the band directed themselves in the television special Magical Mystery Tour – their first critical failure (for the film, at least; the songs, as usual, were fantastic). Increasingly fractured as a band, and distracted by the meditation techniques of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Rishikesh, they were only connected by a thin thread to their third United Artists film, which was produced by Al Brodax, responsible for their 1965-1967 animated series, The Beatles. The band consented to hand over a mere four exclusive songs for the film – a far cry from the complete original albums which they created for the Lester pictures. Clearly the Beatles, who disliked the TV series, didn’t prioritize the film version very highly; John and Paul each wrote one song, and George, taking the rare advantage, wrote two. They wouldn’t even voice their own characters, only appearing in a token live action cameo at the film’s end. But Brodax and director George Dunning (who also worked on the TV series) had greater ambitions for the film: Yellow Submarine would adapt its form and style to the psychedelic spirit of Revolver and Sgt. Pepper. Over the course of eleven months, an army of animators and artists, many of them young students laboriously coloring each individual cel, would produce a film worthy of the Beatles legacy.

George (Peter Batten), Ringo (Paul Angelis), John (John Clive), and Paul (Geoffrey Hughes) disguise themselves as Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Luckily, Brodax and Dunning were given permission to dip beyond those four original contributions and go deep into the Beatles’ classic 1965-67 catalog, creating a musical that picks up their discography where Help! left off. (The original soundtrack album featured the title track and the new songs on the A-side, with excerpts from music producer George Martin’s score on the B-side. The 1999 Yellow Submarine Songtrack excises the instrumentals and features all of the film’s songs.) So along with the new material you get animated versions of “All You Need is Love,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” “Eleanor Rigby,” “Nowhere Man,” “When I’m 64,” “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” and more, many of them just as much stepping stones in the evolution of the music video as the experimental promotional films which the band had begun to make for television a few years earlier (“Rain,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” etc.). One of the reasons the film has endured so well over the decades is the timeless quality of the music; the story, too, is fairytale enough to keep the film from feeling dated, even if the eye-popping visual style embodies the 1960’s. Heinz Edelmann, a freelance commercial artist from Germany, redesigned the Beatles to fit the psychedelic age, pulling them away from the Disney-esque cartoonishness of the TV series toward a character design that violated more than a few rules of animation. The Yellow Submarine Beatles are less flexible but more visually arresting. The characters have a deliberate two-dimensionality, like moving paintings, with pale faces, tiny eyes, long legs thickening into bell-bottoms, and vertical lines that smoothly curve at the edges, transforming the Fab Four into monoliths.

"Only a Northern Song," a sardonic George Harrison quickie transformed by the animators into psychedelic splendor.

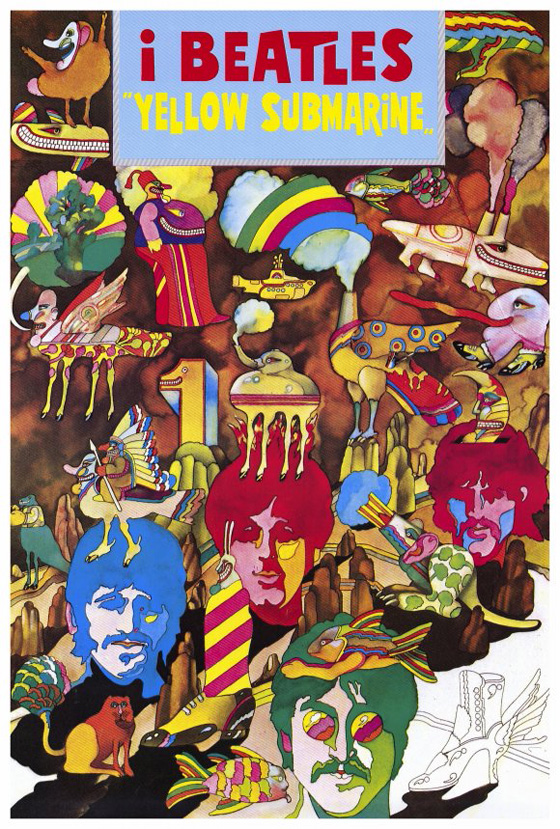

They occupy a landscape that ignores more laws of animation: the world of Yellow Submarine has no consistency or logic in terms of style, spatial relationships, or physics, an intentional decision to keep the film visually intriguing from one sequence to the next. It’s like 90 minutes of a concert poster at the Fillmore come to kaleidoscopic life. Liverpool is represented as a collage of Xeroxed photographs (as an in-joke, many of the faces are members of the crew), dressed in drab colors to match the sadness of “Eleanor Rigby” while the bright-yellow submarine drifts through the sky. The Beatles’ home is a vast mansion of endless halls and hundreds of doors, each of which reveals another dimension (an oncoming train or a scene from King Kong), or spits forth a randomly appropriated pop art object: winking glasses, a skull and crossbones, an umbrella, a bowler hat. Once John (John Clive), Paul (Geoffrey Hughes), George (Peter Batten), and Ringo (Paul Angelis) board the Yellow Submarine on a voyage to save Pepperland from the Blue Meanies, the film embarks on a real head trip (signaled by the orgasmic orchestral build from the end of “A Day in the Life,” and a rapid-fire series of photographs of soaring over the English countryside). The Sea of Monsters lets the animators’ imagination cut loose with many bizarre creations, most notably a vacuum cleaner beastie that sucks up the entire film, leaving the submarine trapped in a white void, like something out of the classic Chuck Jones short “Duck Amuck.” The Foothills of the Headlands is a series of heads bisected so we can read their thoughts (“Freud,” “De Sade,” “E=MC²”). The Sea of Holes is perhaps the most memorable of these surreal landscapes, two planes of perfectly aligned black elliptical dots stretching into the distance, which Dunning pans across to dizzying effect. By comparison, Pepperland seems more conventional, but it does provide an Edelmann playground for the most directly symbolic visual scheme of the film, with the Blue Meanies systematically draining the land of any other color, and transforming the Pepperlanders into black-and-white statues.

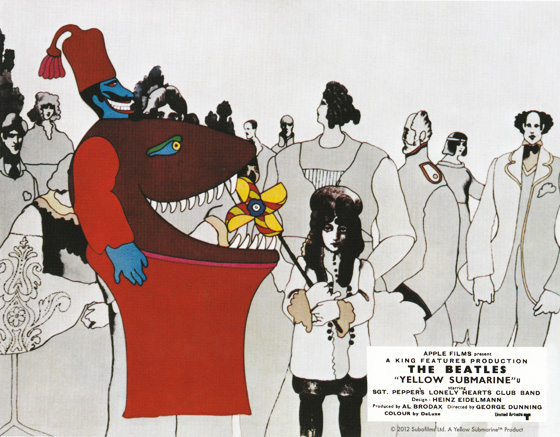

Lobby card for "Yellow Submarine" depicting one of the Blue Meanies, a Snapping Turk.

All of this would be for naught if the script didn’t capture the wit and joy of the Lester films; the truth is that you don’t really miss the authentic voices of the Beatles, for their doppelgangers are just droll enough to sell every silly joke. (The script is the work of Lee Minoff, Brodax, Jack Mendelsohn, and Love Story author Erich Segal. John Lennon later made the claim that he also contributed ideas.) It’s now difficult to imagine the canon of the Beatles without key moments from Yellow Submarine, such as the wonderful “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” sequence – pushing the art of rotoscoping to imaginative ends via bright, sloppy splashes of paint – or the Chief Blue Meanie (Angelis again) overcome by the truth that All You Need is Love, his puffy blue body sprouting flowers. A 1999 marketing blitz reintroduced the film to a new generation via a (non-anamorphic) DVD and a brief theatrical re-release, along with toys and other assorted merchandise. Thirteen years later, the Blu-Ray has finally arrived, and it’s a significant visual and aural upgrade (you can be a purist and choose the original mono soundtrack – available as an option on the disc – but the 5.1 remix of the Beatles music is truly spectacular). It’s highly recommended. Yellow Submarine perfectly embodies the innovation and restless creativity of the band that inspired it. Surely the Beatles realized after attending the film’s premiere that outsourcing their third film wasn’t a bad idea after all.