“Ooh, sparkly!” So spoke my wife at the opening image of Lisztomania (1975), a metronome bedecked in glitter, ticking away on a table in a silvery bedchamber. How could she have doubted me? A moment earlier, she’d said, “This film had better hold my attention…I’m very, very tired.” “It’s Ken Russell,” I told her. “I would be very disappointed if it didn’t.” Russell pans away from that metronome, as Franz Liszt, played by The Who’s Roger Daltrey, grapples with the breasts of his mistress, the Countess Marie d’Agoult, and kisses them one at a time, left and right, in time with the metronome. The Countess increases the beats. He kisses her breasts faster. She bats the metronome up another notch; he breathlessly keeps time. Her enraged husband bursts into the room, and after a slapstick, bawdy duel, Liszt and the Countess are imprisoned within a piano upon railroad tracks, in the path of an oncoming locomotive. And my wife stuck through all 103 minutes; she drank it to the last dregs, when Liszt dive-bombs Berlin in a giant pipe organ spaceship powered by the singing voices of his lost loves, blowing a Frankenstein Hitler to smithereens. He sings a song as he pilots his ship into the cosmos, and “The End” triumphantly appears. She was a tad speechless by that point, but awake.

At a Liszt piano concert, adoring adolescent girls pack the house, swinging their fans and chanting the virtuoso's name.

In many ways, Lisztomania only makes sense in the context of Ken Russell’s career; it’s auteurism at its most extreme. Russell had made several important and controversial films for the BBC in the 60’s, and with his big-screen D.H. Lawrence adaptation, Women in Love (1969), was nominated for an Oscar. Never again would he be so accepted by the mainstream, but his fiery talent was undiminished in his brilliant Tchaikovsky biography, The Music Lovers (1970), one of the greatest films of the 70’s, though many contemporary critics loathed its delirious excesses, including Vincent Canby (“the implication of The Music Lovers is that [Tchaikovsky] was simply boiled to death, which is what the movie does to his genius”), Roger Ebert (“poor Tchaikovsky”), and Pauline Kael (“it is so vile”); as though in defiant retort, Russell followed it up with The Devils (1971), one of the most notorious films ever made, and still unavailable on DVD in the U.S. (a fact I expect to be remedied soon, now that the U.K. finally has it). The shocking, disturbing, occasionally funny, but genuinely angry film pushed Russell even further into the realm of “pure cinema.” Perhaps if he were French and working out of La Nouvelle Vague in the 60’s would critics accept his blatant personal stamp on historical and biographical material. In retrospect, it’s easier to appreciate that Russell was avoiding the tedious and dry type of Oscar-baiting biopics we get year after year; after The Boy Friend (1971), a musical starring Twiggy, Russell delivered the unconventional biographies Savage Messiah (1972) and Mahler (1974). Then came Tommy (1975), one of his most popular films, thanks in no small part to the pre-existing phenomenon of its source material, and – fast on its heels – Lisztomania, like a prefab sequel and a chaser that leaves you zonked out of your mind.

In the domain of Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (Sara Kestelman).

He began filming Lisztomania (from his own script) before Tommy was released, allowing a one-two punch in 1975 of Roger Daltrey/Ken Russell rock musical spectacle. (Though Pete Townshend is absent, his face appears in the likeness of a saint in Princess Carolyne’s Roman Catholic-themed palace, along with the faces of Elvis Presley and Elton John. Also, there are giant penises.) Both films were hits in the U.K. So Lisztomania is not only the product of Russell pushing himself (and his enraged critics) further and further to that ill-defined edge. It’s also a byproduct of his fruitful collaboration with The Who – that meeting of surprisingly like minds, though it would be Rick Wakeman of Yes who would write the music for Lisztomania – and a time capsule of the 1970’s as a decade of boundary-pushing excess. Needless to say, it was his most unconventional classical composer bio yet, but the notion of portraying Franz Liszt (1811-1886) as a rock ‘n’ roll star makes a certain amount of sense. Yes, there really was a phenomenon dubbed “Lisztomania,” and by all accounts it was every bit the 19th century equivalent of Beatlemania. When Russell portrays a Liszt piano concert as an audience-baiting rock spectacle, replete with groupies and an audience of adoring teenage girls, there’s an element of truth. A 2011 NPR story on the phenomenon of Lisztomania remarks, “He’d whip his head around while he played, his long hair flying, beads of sweat shooting into the crowd.” In the same article, pianist Stephen Hough notes, “We hear about women throwing their clothes onto the stage and taking his cigar butts and placing them in their cleavages.” Surprisingly, that is something Ken Russell does not portray, but there is an amusing sequence of a lackey gathering information on all the beautiful women in the audience in whom Liszt is interested, reporting back with giant placards: “MILLIONAIRESS,” “MOST PROMISING ACTRESS,” and finally, “PRINCESS.”

The Pope (Ringo Starr) talks to Liszt (Roger Daltrey) while a nude groupie ("Little Nell" Campbell) looks on.

Roughly, the biographical details are correct. Liszt steals away Marie d’Agoult (Fiona Lewis, Tintorera), wife to a French Count (Savage Messiah‘s John Justin). Their children include Cosima Liszt (Veronica Quilligan), who later marries Hans von Bülow (Andrew Reilly), then Richard Wagner (Paul Nicholas, Tommy). Liszt separates from his wife and falls under the guidance of Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (Sara Kestelman, Zardoz), who encourages him to focus on composing. Their plans to wed are thwarted by the church (here embodied by Ringo Starr, playing the Pope). Liszt becomes a Franciscan abbé, and among his titles is that of exorcist, which Russell embraces in full-on William Friedkin fashion. Historically inaccurate: Liszt never tried to exorcise a vampiric Wagner, here seen plotting to create an army of supermen (in both the Nietzsche and D.C. Comics meaning) from his Gothic castle, and becoming reborn as a Frankenstein Hitler. That never happened. It is also unlikely that Liszt was ever locked in a chamber by a Russian (Russell favorite Oliver Reed, in a cameo) and nearly suffocated by stone asses in the walls jetting toxic fumes.

Ken Russell does Hammer horror: Richard Wagner (Paul Nicholas) is revealed to be a vampire, though Liszt's daughter, Cosima (Veronica Quilligan), sticks beside him.

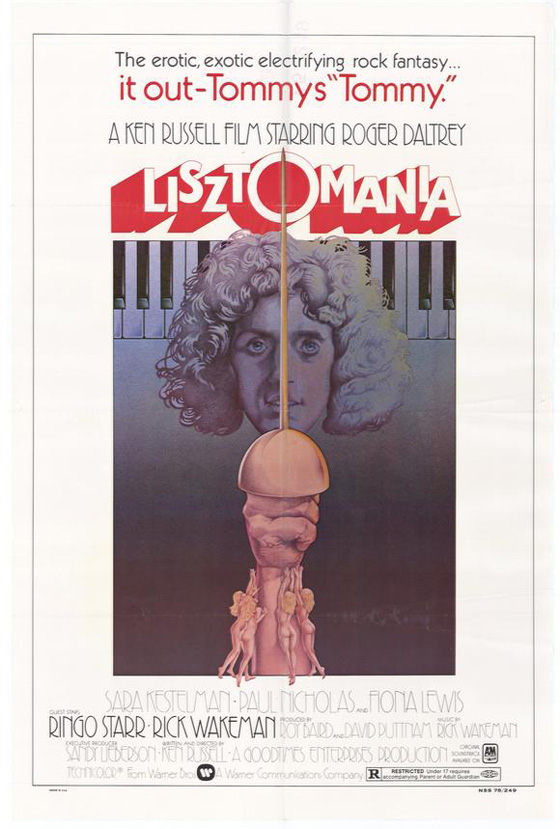

But opulent, midnight-movie spectacle is obviously the point. 1975 saw not just the release of this film and Tommy, but also The Rocky Horror Picture Show, adapted from the London stage hit. (One scene in Lisztomania seems to be inspired by the stage version of Rocky Horror, as mad scientist Wagner builds a “Thor” who is not unlike Dr. Frank N. Furter’s Rocky.) Rocky Horror‘s Columbia, “Little” Nell Campbell, has a small but memorable role in Lisztomania as a nude groupie whom Daltrey fails to hide from the visiting Pope. (Starr’s papal wardrobe, decorated with photos of movie stars, is a thing of beauty.) Now, Lisztomania was a #1 hit in the U.K. People saw this in the middle of the day, dead sober; I can’t help but imagine them taking in a 12:00 showing of the film, with Daltrey’s fever dream in the palace of the Princess Carolyne, a musical sequence in which he parades about with a twelve-foot cock, allowing his female admirers to do a Maypole dance around it, until the Princess guides it straight into a guillotine. (Fair enough. A moment earlier, he was literally climbing through her panties and into her uterus.) I suppose the warning was right there in the film’s poster, which depicts Daltrey wielding an overtly phallic sword while women swoon over it. There have never been so many giant penises in a major motion picture, so Lisztomania might as well advertise it as an asset.

Russell's depiction of Liszt in Heaven, musically accompanied by the women in his life.

Mind you, there is no real symbology in Russell’s world. Nothing is “phallic”; it is simply a penis (is a penis is a penis). When Russell improbably leaps forward to World War II, he depicts the Holocaust as a street of bearded Orthodox Jews hastily hiding their giant Stars of David before the stormtroopers arrive, that Frankenstein Hitler and his Nazi supermen. And a swastika is a swastika is a swastika. Whether or not this is the height of tastelessness (the Holocaust as a Pop Art cartoon) is beside the point – if you’ve come this far, you might as well watch Franz Liszt swoop down in a spaceship from Heaven and blow the Third Reich to bits. Russell, at this point, has successfully rendered his critics irrelevant: he’s won. I couldn’t even tell you if Lisztomania is good or bad (to paraphrase Nietzsche – you know, that guy whose name adorns Wagner’s hat – the film is beyond all that). It’s a unique experiment: what happens if we do an erotic rock musical about Franz Liszt? Sit back and watch; you’ll learn many things, such as that Roger Daltrey, surprisingly, does a mean Charlie Chaplin impression.

Lisztomania is now available on DVD from the Warner Archive. It looks and sounds great.