“Men all say they worship an altar of virginity. But they value their enjoyment more than anything. So in practice, seek out depravity,” instructs Juliette to her innocent sister Justine while lying in bed at their convent. She then declares, “I intend to do it grandly!” So the stage is set. Justine: The Misfortunes of Virtue (aka Cruel Passion, 1977) is a curious low-budget film, an attempt to straddle the two genres which the poverty-stricken British film industry of the 1970’s seemed hamstrung to produce: highbrow literary adaptations and lowbrow exploitation. Surprisingly, it isn’t really all that exploitative, particularly in comparison with what was really raking in the cash in British cinemas back then. Director Chris Boger, who cites Bergman as an influence and shot live footage for Led Zeppelin, plunges into this Marquis de Sade adaptation (with a screenplay by actor Ian Cullen) with intelligence and respect, though one might rightfully ask what audience he was seeking. It has too much skin, violence, and sadism for the critics, and not enough of those for the grindhouse crowd. Yet I think de Sade might have found satisfaction in certain moments of this condensed and stripped-down version of his prose. Or perhaps he would have empathized with the film’s fate: his works were ignored by contemporary critics as well. The Marquis used sensationalism and shock value as a syrup to allow the reader to swallow his ideas and philosophy; and if it’s far from being an undiscovered classic, Boger’s Justine at least makes a valiant attempt to represent what de Sade was all about.

Justine's sister Juliette (Lydia Lisle) protests the unconsecrated burial of their parents.

Confession: I have a weakness for stories about debauched Catholics; I don’t know why. Matthew Lewis’ 1796 book The Monk is one of my favorite novels, as is Balzac’s bawdy Droll Stories. Jacques Rivette’s The Nun (1966), in which Anna Karina is lusted after in a convent, is a film I adore. So automatically I was engaged with the opening half-hour of Justine, as two teenage sisters fend off the aggressive, lecherous advances of a Mother Superior (Maggie Peterson) and the more tentative and confused urges of one Sister Claire (Malou Cartwright). The sisters seem to be diametrically opposed, but are fiercely loyal to one another. Juliette (Lydia Lisle, The Elephant Man) acknowledges the power of her feminine charms, using them to tease the hot-and-bothered Sister Claire. Justine (Koo Stark, Emily) is devoted to a life of virtue, which only infuriates the Mother Superior, who describes her as “devout, almost to the point of pride” (a similar criticism is delivered in Black Narcissus regarding Sister Clodagh). When Justine rebuffs the Mother Superior’s sexual overtures, the girls are turned out of the convent with the little money left to them by their recently-deceased parents. Justine is still recovering from the tragic news: their father hung himself – a mortal sin – and their mother died of the shock; both have been buried in unconsecrated ground by the scornful nuns, and the notion that her parents might be damned to eternal hellfire occupies Justine’s imagination.

Madame Laronde (Katherine Kath) instructs the sisters in her brothel.

Juliette’s plan for their livelihood – as she describes it to her would-be lover, the handsome but amoral Lord Carlisle (Martin Potter, Fellini Satyricon) – is to take their precious virginity and sell it at the highest price at a brothel run by the worldly Madame Laronde (Katherine Kath, The Prisoner‘s Madame Engadine in the classic episode “A., B. & C.”). Justine would rather not, but has little choice but to come along. Laronde’s method of instruction involves using the brothel’s resident simpleton, George (Barry McGinn), whose unflagging potency allows plenty of helpful classroom exercises for Juliette. Inevitably, Justine runs away, taking shelter with Pastor John (Louis Ife); as one might expect in a de Sade tale, the pastor is unable to restrain his lusts for long, and his pursuit and attempted rape of Justine ends with his accidentally plummeting to his death. She escapes this encounter only to fall in with a band of thieves robbing her parents’ grave; they brutally coerce her into assisting in their daytime profession as highwaymen. This only leads to further mayhem, murder, and tragedy, as Justine’s attempts at a life of virtue are undone by a world where only wickedness is rewarded.

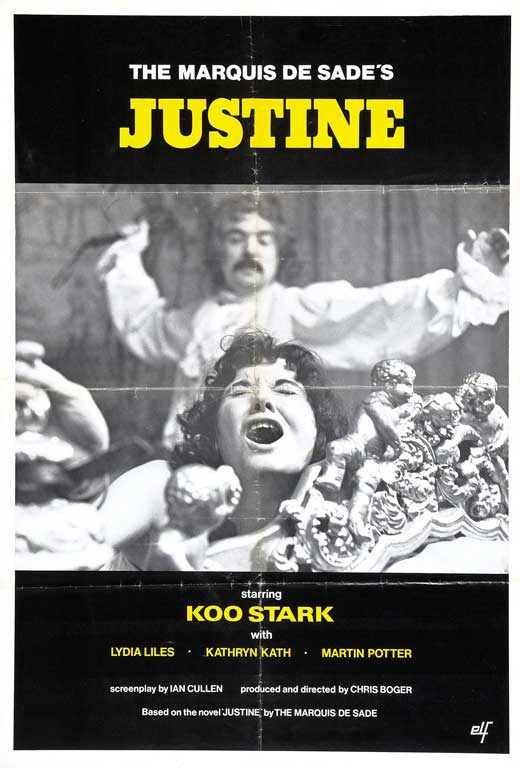

The innocent and doomed Justine, played by Koo Stark.

The downbeat ending ought to be depressing, but it cannot be when the characters are so clearly concepts rather than real people. Justine’s attempts at living a life of pious virtue are doomed from the start, and so her fate is observed at an almost clinical remove. The film is populated by archetypes, and there’s an appropriately chilly quality throughout which is leavened only by the attractive photography by a young Roger Deakins (No Country for Old Men) and fine performances from the cast, particularly Lydia Lisle as – let’s face it – the more interesting of the siblings, with her appetite for the forbidden. Boger’s occasionally workmanlike direction is at least peppered with a few moments of surrealism, such as a dream sequence in which Justine imagines her tormentors as vampires and ghouls. One striking shot depicts the Mother Superior greedily counting out coins on the leather cover of a Bible; the story demands more images like this, which are more plentiful and brilliantly applied in Buñuel’s filmography. Inevitably, Justine never rises to that level. The library-music score is particularly distracting – during one key moment, we hear a melodramatic cue which had already been overused by Monty Python’s Flying Circus; unintended laughter is inevitable. As an attempt to make an adult, literate treatment of de Sade’s ideas for the screen, the verdict on Justine must be “nearly, but not quite.” Those seeking out Redemption’s 2012 Blu-Ray of the film may as likely be interested in star Koo Stark, who would be romantically linked to Prince Andrew before he married Sarah, Duchess of York. Her film career never quite took off, and the same year Justine was released, her small role in Star Wars fell to the cutting room floor.