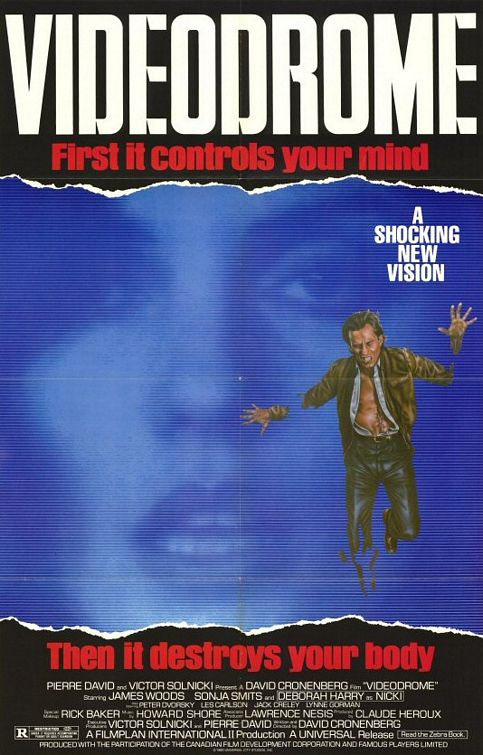

It was announced last week that Videodrome (1983) would be remade, most likely as a PG-13 film and with a screenplay from the man who wrote the last two Transformers movies. This news – yet another 80’s cult classic will be reworked, watered down, and spat out indifferently into theaters – is disheartening, to say the least. But I actually believe that Videodrome is a movie that could be successfully updated to the new millenium. (I thought this of Tron, as well, given how prescient that film was for the perpetually-online generation. But the unimaginative Tron: Legacy was not what I had in mind.) Think about it. Think about the Atari cartridge sitting upon James Woods’ bulky, early-80’s television set; I sincerely believe director David Cronenberg intended this as something ominous: video games – and Atari 2600’s – allow for users to plug into a virtual world in the privacy of their own home (never mind the frustration of actually trying to play an Atari game). Later in the film, Woods will lean into the flexing, breathing screen of his television to bury his face into the giant, red, beckoning lips of Debbie Harry, as the “viewer” transitions into a “user” in a more sensual (and creepy) experience than 1980’s video game technology could deliver. But Cronenberg was (and is) a visionary, and revisited these concepts in the underrated eXistenZ (1999), an overt Philip K. Dick homage which could also double as a Videodrome sequel, and one, I’ll wager, more engaging and creative than the remake Hollywood is now inevitably preparing.

On a first date, Max Renn (James Woods) discovers that Nicki Brand (Deborah Harry) cuts herself for pleasure.

The mere notion that a remake could be PG-13 is laughable given that the script Cronenberg originally wrote would have garnered an X. Not that his script was ever really finished; it was more of a purging of his subconscious, David Lynch-style, unfiltered onto the page. It was being constantly rewritten during filming, and the ending was altered at the last moment, giving us the abrupt but highly memorable climax with Woods, a television, and his literal hand-gun. Videodrome unfolds like a nightmare, escalating into illogic – or dream-logic – very quickly, and the ending we now have is appropriate for a nightmare that has reached its ugly termination point, when you might wake up suddenly in a cold sweat. (Then again, maybe that does describe the Transformers films.) The final version of the film is cohesive but effectively surreal, an adult fable for the video age. Woods plays Max Renn, the equivalent of a film noir detective: amoral, ironic, jaded; only he’s not on the trail of missing persons, but the edgiest possible content that he can broadcast on a crass channel called Civic TV. He becomes fascinated by an S&M program called “Videodrome,” broadcast on a pirate channel discovered by his tech-geek friend Harlan (Peter Dvorsky); in the 40’s, this character might be played by Peter Lorre, and Renn might meet him in a smoky club or a dark alley for his contraband goods. The concept of “Videodrome” is crude: a single camera filming a room with rusty-red walls and masked men whipping and electrocuting their naked victims. Harlan says, “There’s no plot. It goes on like that for an hour: torture, murder, mutilation.” Which Max interprets as: “It’s absolutely brilliant. There’s no production costs. You can’t take your eyes off it.” (In other words, reality TV.) At first Harlan thinks the signal is coming from Malaysia; then he discovers it’s actually being broadcast from nearby Pittsburgh. As with so many Cronenberg films, the enemy is within.

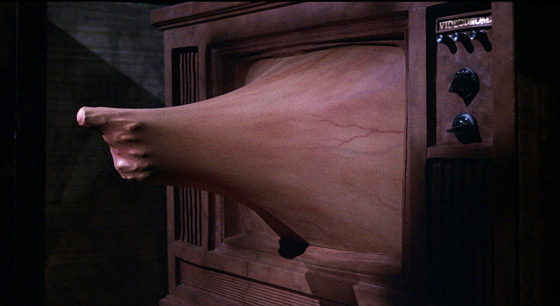

Max hallucinates his television reaching out and offering him a weapon.

Renn doesn’t realize that his dark journey begins the moment he starts viewing the pirate broadcast. Even to watch is to be implicated; that’s how “Videodrome” functions, like being exposed to radioactive material. And his journey is hastened, somehow, by becoming interested in Nicki Brand (Harry), whose cold, reserved exterior hides a secret life of sadomasochism; she is destined to be the first to dive down the rabbit-hole of “Videodrome.” Rather than being repelled, Renn is fascinated. He is the typical Cronenbergian protagonist: an explorer into the unknown, regardless of the risk. That risk, of course, is biological transformation. Cronenberg’s characters flower into something remarkable – frightening at first, but new, and the director treats these transformations and mutations with obsessive interest. “Long live the new flesh.” But there’s a fine line Cronenberg walks in Videodrome. We learn, as the plot unfolds, that the program emits a video signal that produces a tumor in the viewer (which, in turn, causes hallucinations); the broadcast is a weapon. The script could easily turn into a condemnation of the effects of sex-and-violence programming on the viewer, like those news reports which describe a mass murderer by the films he watched and the video games he played. But Cronenberg refuses to succumb to anything simplistic. He expects an eventual merging between man and his technology (thus, eXistenZ). It’s not that merging we should beware, but how it’s used; Max becomes a puppet of greater forces, literally programmed like a VCR: a vaginal slit opens in his stomach, where pre-recorded cassettes can be inserted and which produces a gun that merges with his hand, firing cancer at his targets. In the wild final half-hour of the film, Max ping-pongs from one manipulating agency to another, helplessly enacting their causes. Sex and violence prove to be nothing more than a smokescreen for the real danger: government mind control.

Max hallucinates that he enters the world of "Videodrome."

But what a smokescreen! Videodrome gains its electric charge from the taboo world Max explores, starting with the “tame” softcore entertainments of “Samurai Dreams” and advancing into some queasy and violent realms (Is it for real? Are these political prisoners? People snatched off the streets of Pittsburgh?), until finally the television is reaching out for Max, and he finds himself drawn into its world (whipping a screaming television, in one of cinema’s strangest moments). The effects, by Rick Baker, Michael Lennick, and Frank Carere, are occasionally gruesome but wondrously tactile, in the pre-CG era for which many of us are now nostalgic; this, and John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), demonstrate how creative FX artists could be without relying upon computer graphics. I also found myself nostalgic for television sets with dials, and the now-forgotten possibilities of discovering some strange, fuzzy transmission high up in the UHF dial. If you adjust your rabbit ears just so. If you don’t grow those fleshy appendages right out of your head in the effort. Remake this? Videodrome? Better to reach into the darkest corners of your own brain and produce an original waking nightmare for the internet age; only that approach would honor Cronenberg’s intentions.