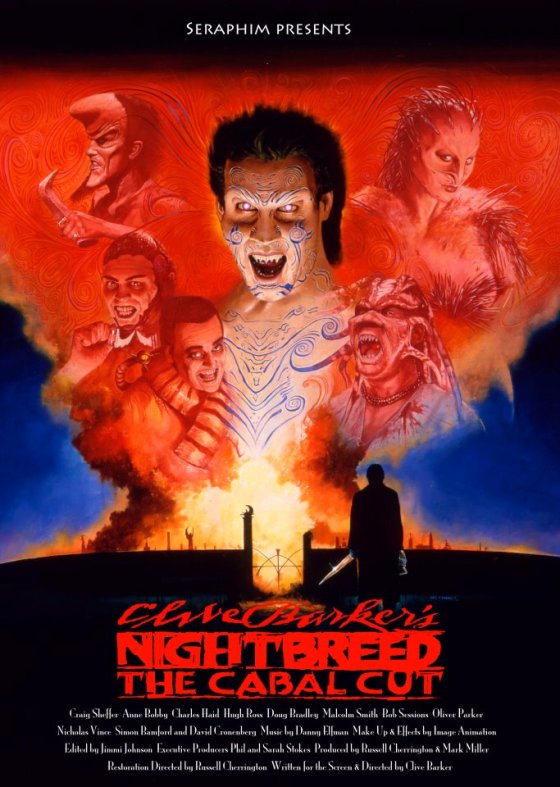

“I wanted to see more of Midian,” said Russell Cherrington when asked why he decided to restore Clive Barker’s Nightbreed (1990) to its original length of 155 minutes. It was a good answer, as far as I was concerned. He might as well have said, “I really like monsters. We all do, and that’s why we’re here.” The occasion was the July 13th screening of the long-awaited “Cabal Cut” of Nightbreed at Chicago’s Portage Theater. Cherrington, who attended the screening with actress and singer Anne Bobby (who plays Lori in the film), has spent years assembling the most complete cut of the film possible, using workprints and rough cuts, some of which were discovered, he states, buried behind some books in Clive Barker’s bookshelf. (I would like to imagine he pulled the horn of gargoyle and the shelves slid aside, revealing a secret alcove of Barker’s lost treasures, but this was probably not the case.) He had to work from cassettes of inferior quality to stitch together Barker’s original vision of the film, using the screenplay as a guide. And it’s a patchwork object, rough to say the least, with some moments of sound dropping out, and the rare footage washed-out and grainy. But when he showed the author/director/artist the final product – just recently revised and expanded from earlier “Cabal Cut” screenings – Barker was moved to tears. There was his film. He’d forgotten what it was.

Boone (Craig Sheffer), at the gates of Midian, encounters two of the Nightbreed, Kinski (Nicholas Vince) and Peloquin (Oliver Parker).

When Nightbreed was released in 1990, it was a foregone conclusion that it would find its audience over time, and over home video, rather than on its initial theatrical run: it had “cult following only” written all over it. Barker, having struck gold with Hellraiser (1987), was taking the opportunity of success for a film that would stretch the limitations of horror cinema even further. Both were based on novellas he’d written; Nightbreed would adapt Cabal, the tale of a man named Boone who discovers Midian, the subterranean realm of an ancient race of shapeshifters. But the true monster is revealed to be his psychiatrist, Dr. Decker, who has a secret life as a serial killer, and frames his patients for his crimes. It was an ambitious project for a genre film, not just in its scale (constructing an underground city of monsters) but in its unconventionality. Much more so than Hellraiser, Nightbreed is representative of Barker’s fiction – violent, sexual, with strong elements of the fairy tale, and a fascination with the wonders of transformation. To that latter point, Barker has something in common with director David Cronenberg; so it was only natural to hire Cronenberg for the role of Dr. Decker. (He’s excellent.) Craig Sheffer, with an uncanny resemblance to David Boreanaz of Angel, was cast as Boone, and Pinhead himself, Doug Bradley, was once more buried under elaborate makeup to play the Nightbreed’s leader. The score was supplied by Danny Elfman, at a creative peak following his work on Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure (1985), Beetlejuice (1988), and Batman (1989), not to mention his memorable TV themes for The Simpsons and Tales from the Crypt. Ralph McQuarrie of Star Wars fame provided matte paintings and designed the opening credits mural.

David Cronenberg as Dr. Decker, psychiatrist and serial killer.

Barker’s sophomore effort effectively balances its shocks with the more challenging ideas of his fiction; there’s gore for the gorehounds, but the story and characters are more nuanced than your typical slasher film or monster movie (and this film incorporates elements of both). The Nightbreed aren’t sinister, but neither are they harmless. They can be genuinely beastly, when roused, and they don’t take kindly to strangers. Many of them are physically repulsive and frightening, a fact from which Barker doesn’t shy, but he nonetheless emphasizes the attraction of Midian for the humans who seek it out. “To be able to fly, to be smoke, or a wolf?” one of the Nightbreed tells Lori. “To know the night and live in it forever? That’s not so bad. You call us monsters, but when you dream, you dream of flying, and changing, and living without death. You envy us, and that which you envy…” …we destroy, and the second half of the film picks up on that theme with a siege of Midian by a cast of humans both hateful and jealous, including a mad priest, Ashberry (Malcolm Smith). Ashberry’s presence underlines one of the film’s leitmotifs, fanaticism, and likely points to Midian’s origin as an obscure Biblical tale, a city whose population was slaughtered at Moses’ command for tempting the Israelites into sin. (Numbers 31, 1-2: “And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying, ‘Avenge the children of Israel of the Midianites.'”) Barker seems to be indicating that the most righteous rage is rooted in the most intense envy. But what’s clear is that Nightbreed, like much of Barker’s fiction, places its sympathies with the Other when pitted against the status quo; just as the surviving Midianites have been hunted, tortured, and executed over the centuries, Barker seems to invite the viewer to compare the “Cabal” to any traditionally maligned minority group. A queer reading is obligatory in light of the author’s sexuality, but – again – what makes Nightbreed so interesting is that the Other has teeth.

Lori rescues one of the Nightbreed children from the harmful rays of the sun. In the "Cabal cut," we learn of Lori's developing psychic connection with the child.

Nightbreed was heavily cut by Twentieth Century Fox upon its release, a pointless endeavor since they didn’t really understand the genre-bending project in the first place (Barker was deeply upset when he saw how the studio misrepresented the film through its marketing). The final 102-minute cut is a drastically simplified version of the new “Cabal Cut,” but for decades it was the only film the fans had, and it developed an earned following among horror fans. As someone who came to Barker through his novels and short stories instead of his films, I always liked Nightbreed but never loved it; something seemed off, though I couldn’t quite put my finger on it (admittedly, the film got better with each subsequent viewing – there’s a lot of heady material to unpack in 102 breathless minutes). Now having seen the Cabal cut, I can attest the film is both greatly improved and more flawed, if that’s possible. To the good news: much of the excised material is valuable character development between Boone and Lori – we get to see them as lovers so their separation feels more tragic. (Anne Bobby also loses a nightclub musical number in the final cut, which is unfortunate given her splendid voice.) We do see more of Midian, but the most significant loss to the Nightbreed sequences is Lori’s relationship with the shapeshifter child she’s seen rescuing from the daylight in the finished cut. In the Cabal edit, we watch as she develops a psychic connection to the child, suggesting that she, too, is one day destined to join Midian. (This also gives her a stake in Midian’s fate.) Much of the material is simply extended versions of existing scenes, such as some additional dialogue between Boone and Narcisse (Hugh Ross) in the hospital, which helps develop their relationship while establishing the importance of Midian. There’s more of Ashberry and the final siege on Midian, but too much, I fear: the climax now seems to drag on forever. At 155 minutes, Nightbreed overstays its welcome, and viewers are likely to feel exhausted by the time the credits roll. But if Russell Cherrington were to now trim the film back some more, he’d find a happy middle ground between the “Cabal Cut” and the too-brief theatrical version. This quibble doesn’t really matter; there’s time for that later, if we can just convince Fox and Morgan Creek to go back to the vaults to find the original footage (rather than the rough-quality workprint tapes Cherrington used), and then perhaps have Barker himself edit his own cut of the film. Cherrington is screening Nightbreed: The Cabal Cut at select venues to raise interest and money for the endeavor, and if we’re lucky, we’ll see Barker’s original vision on Blu-Ray someday soon. It’s not a perfect film, but it’s becoming more evident than ever that it’s a significant one. You can find more info at Occupy Midian.