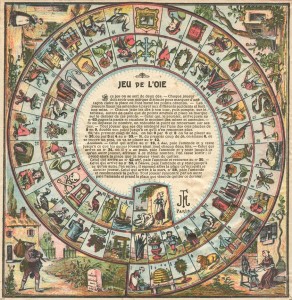

There is an ancient game called jeu de l’oie, or the “Game of the Goose.” Players throw dice and progress through a spiral path divided into sixty-three spaces. The goal is to be the first to reach the center, and landing on a Goose or a Bridge can be advantageous, advancing your piece further along the path. But many of those spaces contain traps, the nature of which varies from board to board. You can be delayed by landing on the Prison or the Inn, and if you’re unlucky enough to land on Death, you will be plunged back to the start. It’s an ancient game of uncertain origins, but provided the literal roadmap for modern-day board games such as Monopoly or The Game of Life. Wikipedia informs me that in Jules Verne’s Le Testament d’un excentrique (The Will of an Eccentric, 1899), part of his Voyages Extraordinaires series of novels, a millionaire wills his fortune to the one who can complete his Game of the Goose-inspired treasure hunt that uses the United States as one vast game-board (which means that Verne can list It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World as one of his many successful predictions). Eight-two years later, filmmaker Jacques Rivette would make Le Pont du Nord (The North Bridge, 1981); halfway through the film, the two main characters realize that the nonsensical series of events in which they’re entangled can actually be mapped to the Game of the Goose, and by following its rules, they might progress one space at a time toward a solution – a goal that lies somewhere within the streets of Paris.

There is an ancient game called jeu de l’oie, or the “Game of the Goose.” Players throw dice and progress through a spiral path divided into sixty-three spaces. The goal is to be the first to reach the center, and landing on a Goose or a Bridge can be advantageous, advancing your piece further along the path. But many of those spaces contain traps, the nature of which varies from board to board. You can be delayed by landing on the Prison or the Inn, and if you’re unlucky enough to land on Death, you will be plunged back to the start. It’s an ancient game of uncertain origins, but provided the literal roadmap for modern-day board games such as Monopoly or The Game of Life. Wikipedia informs me that in Jules Verne’s Le Testament d’un excentrique (The Will of an Eccentric, 1899), part of his Voyages Extraordinaires series of novels, a millionaire wills his fortune to the one who can complete his Game of the Goose-inspired treasure hunt that uses the United States as one vast game-board (which means that Verne can list It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World as one of his many successful predictions). Eight-two years later, filmmaker Jacques Rivette would make Le Pont du Nord (The North Bridge, 1981); halfway through the film, the two main characters realize that the nonsensical series of events in which they’re entangled can actually be mapped to the Game of the Goose, and by following its rules, they might progress one space at a time toward a solution – a goal that lies somewhere within the streets of Paris.

Ex-convict Marie (Bulle Ogier) and vagabond Baptiste (Pascale Ogier) try to decipher a mysteriously coded map of Paris.

Those two characters are Marie and Baptiste, women who are strangers to one another but form a fast and symbiotic partnership. (A recurring motif in Rivette’s work are two paired females; and one is deliberately reminded of his classic 70’s fantasy, Celine and Julie Go Boating.) One of the reasons they seem so perfectly matched is that actress Bulle Ogier, playing Marie (and veteran of both Rivette and Buñuel), is the real-life mother of her co-star Pascale Ogier, playing Baptiste. Tragically, Pascale, who appeared in Eric Rohmer’s Perceval (1978) and Full Moon in Paris (1984), would die in 1984 after a drug overdose. Here, Rivette’s camera cannot leave her intense gaze, which can be alternately amusing or unnerving – either naïve or dangerously unhinged. She meets the older Marie through a series of chance encounters, and on the third, deciding it’s fate, commits herself like a loyal dog, looking out for Marie with a knife and some martial arts moves, though it is not exactly clear, at first, why Marie could possibly need protection. Baptiste, a vagabond first seen patrolling Paris on a moped, detects danger everywhere. She tracks the number of lion statues she finds throughout the city, as though they belong to some indecipherable codex, or as if they are beasts that might suddenly lunge at her. When she confronts the ubiquitous advertisements plastered in posters on every wall, she slashes with her knife at the eyes of the models (or, in one case, a samurai in a poster for Kagemusha), paranoid she’s under “surveillance.” Marie accepts her services regardless, though she expresses skepticism that the girl’s name is really “Baptiste” (conspicuously offered only after she said her name was “Marie”), and does her best to convince the girl that the world is not really out to get them. Baptiste has her uses. Marie, who has just been released from prison after serving time for a bank robbery, has developed a phobia for confined spaces, and prefers not to step indoors, even when she just needs to order a croissant or deliver a postcard to her partner, who’s still behind bars. So when one needs to pee in the bushes, it’s handy to have Baptiste keeping a lookout, crouched in defense.

The MacGuffin, a map of Paris sought by gangsters.

But as Marie renews a connection with her lover, card shark Julien (Pierre Clementi), we begin to see the patterns that Baptiste does, like a folie à deux: strange connections, suspicious behaviors, familiar faces. A stranger makes a hilariously botched attempt to switch briefcases with Julien while his back is turned. A motorcyclist Baptiste distrusts at the start of the film now begins popping up wherever they go. Another man turns up dead. Baptiste calls these people “Maxes,” and to her, there’s a Max on every corner, which is why she’s always practicing her karate. When she steals Julien’s briefcase against Marie’s wishes, the two discover a collection of newspaper clippings, many of them sensational headlines regarding the French criminal Jacques Mesrine (who was killed by the police in 1979). Most curious is a map of Paris with a spiral drawn in black marker, which reminds Marie of the Game of Goose. Since they discovered a dead body lying in a graveyard, they use this as the key to decipher the code: they can now number the squares and see exactly where they stand in the game. But Baptiste is so taken by this particular conspiracy theory that she can’t stop drawing connections, and begins to see Maxes everywhere. In one memorable sequence, she envisions an urban flame-throwing dragon guarding a bridge, cementing her transformation into the film’s Don Quixote.

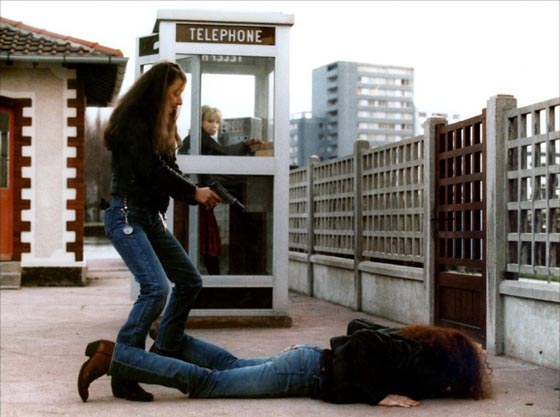

Baptiste confronts a "Max" - actually a harmless foreigner who was reluctant to surrender a phone booth to Marie.

Jacques Rivette helped to invent the French Nouvelle Vague, and yet his work remains so idiosyncratic that it seems reductive to classify him. Although, like his fellow critics-turned-directors from the influential Cahiers du Cinéma, he elevated and revered certain studio films and directors of decades past, he seems just as equally informed by literature (in this case, Cervantes) and the stage; he’s less overtly stylish than many of his peers, and is more concerned with the avant-garde but rigorous construction of his stories, which are like metaphysical labyrinths. His films also tend to be long – the notorious Out 1 (1971) is over twelve hours in length in some versions, though Le Pont du Nord is a more palatable 129 minutes. Doubtless these are all reasons why his films have never been as popular as those of Godard or Truffaut; to date his films are very hard to see in the States since so few are available on Region 1 DVD, and most of my viewings have been in revival screenings (such as this one, in a newly-subtitled 35mm print just screened in Madison). Yet I’ve never found a Rivette film unrewarding; his works are challenging but always playful, with a sharp sense of humor. Le Pont du Nord is intriguing for a number of reasons. As with his earlier films such as Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974) and Duelle (1976), the characters follow strictly outlined rules that, at first, seem random and meaningless, before he finally begins infusing them with purpose and gravity; we have to learn the game before we can play. The names of the doomed lovers, Marie and Julien, are reused in a belated pseudo-sequel, The Story of Marie and Julien (2003), which offers a few intriguing parallels to this film (I must revisit it soon). But what remains with the viewer is the film’s ultimate ambiguity: Marie and Baptiste’s indulgence in the fantastic both rewards and harms them. Rivette anticipates Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985) and especially The Fisher King (1991), in which Robin Williams plays a kind of Baptiste, with Jeff Bridges his accidentally-enabling Marie. The ending is both conclusive and elliptical. We may have reached the goal, yet we are still deep inside the labyrinth.