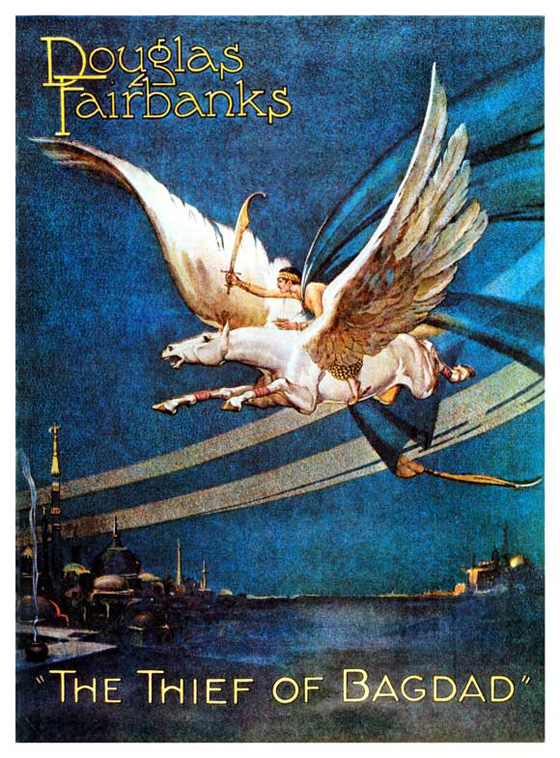

When movies learned to talk, they forgot how to see. The advent of sound was such a distraction that elegant story construction through visuals was temporarily a lost art. Just watch The Thief of Bagdad (1924) to be reminded of how sophisticated silent cinema had become by the mid-20’s. Cinematic language had evolved rapidly in the twenty-nine years since the Lumière brothers patented the cinematograph, and Douglas Fairbanks (1883-1939), whose film career began in 1915, was an important player in the key period of film’s transition into lavish spectacle. (The recent documentary series The Story of Film: An Odyssey posits that The Thief of Bagdad‘s stated moral, “Happiness Must Be Earned,” specifically reflects the morals of Hollywood’s newly monied.) Fairbanks was one of the first movie stars, and helped to define what that meant: athletic, charismatic, and fronting big-budget productions with wide appeal. His Arabian Nights pastiche was released at the height of his popularity (which would decline rapidly when the Talkies came): he made headlines by co-founding United Artists and marrying the most popular actress of the day, Mary Pickford; he was coming off a string of hits, The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), and Robin Hood (1922). He could do no wrong – never mind that his relationship with Pickford began while she was still married – and The Thief of Bagdad sealed the deal. It is a wonder to behold. The towering sets, the imaginative use of special effects, the neck-risking stuntwork by Fairbanks: it is cinema as a visceral dream. Sound would be extraneous.

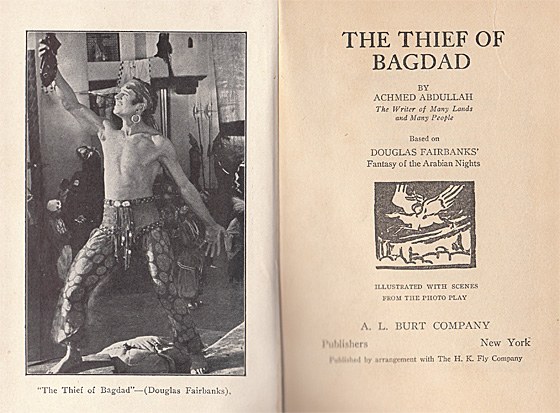

Frontispiece from the 1924 film novelization, written by the then-popular author of exotic romances, Achmed Abdullah.

As for the story itself, it is not faithful to any particular Arabian Nights story, but rather borrows scattered elements to assemble an Orientalist romance and adventure that would seem comfortable to audiences who had enjoyed Fairbanks’ Robin Hood and Zorro. There is a flying horse, as in “The History of the Third Calender” and “The Story of the Enchanted Horse,” and a flying carpet, as in “The Story of Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Pari Banou.” There is an imperiled princess and a valiant hero, as in so many of the Nights. But it’s an original, emerging from Fairbanks’ fevered imagination: he gets a story credit, and was producer, working closely with director Raoul Walsh and production designer William Cameron Menzies. The film is designed to hit every sensationalistic note in its two-and-a-half hour running time: prophecies, monsters, magic, swordfights, harem girls, Mongol invaders, and a dashing thief (Fairbanks) who loses his heart to the Caliph’s daughter (Julanne Johnston). Walsh had been directing films since 1913, but given that he’s now best known for his studio work of the 30’s, 40’s, and 50’s (in particular the classic James Cagney film White Heat), it’s always something of a surprise to be reminded that he helmed a multi-million dollar extravaganza like The Thief of Bagdad. His collaboration with Fairbanks here is noteworthy not just for its scope, but for its delightful affinity with the breathless and imaginative films of Buster Keaton, Charles Chaplin, and Harold Lloyd. The sight gags frequently rely upon Fairbanks’ stuntwork, such as a memorable sequence in which he hops, like a cartoon character, from one oversized jar to another (courtesy a hidden trampoline), or another in which he breezily escapes the Caliph’s palace by walking blindly off a wall, grabbing hold of a tree, and bending it to the ground. Like those great silent comics, he makes it look easy. In the finale, when he and Johnston ride the flying carpet over the throngs of Bagdad, it’s not trick photography: they’re really sailing perilously through the sky on a steel platform suspended by piano wires attached to a swinging crane.

Ahmed (Douglas Fairbanks) holds hostage a Mongol slave (Anna May Wong) beside the bed of the sleeping princess (Julanne Johnston).

But what always sticks firmest in my mind is Menzies’ production design, which consciously evokes fairy tale illustrations. Those extraordinary sets that tower above the actors; the oversized props such as the gigantic jars through which Fairbanks makes his escape; the strangely curved portals and windows, like a more sensuous version of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari; the “shining” streets of the city that are actually polished enamel floors; the huge, multi-limbed idol that squats in the desert; the undersea kingdom of (real) blown glass through which Fairbanks swims before battling a giant spider; or Bagdad’s fearsome gate, which opens in four snaggletoothed sections, like the mandibles of a colossal insect. I first saw this film some years ago with live organ accompaniment at a revival theater that specialized in silent films, and was transported; but the new Blu-Ray from the Cohen Media Group is an ideal showcase, featuring a new restoration, a perfect score by Carl Davis that uses themes from Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, and the color tinting from the original release. The film looks brand new, and in high-definition you are easily lured into the world of The Thief of Bagdad.