After a decade of hits in his native U.K., Ken Russell arrived in Hollywood with the mind-bending Altered States (1980). It’s the story of an experimental psychologist, Eddie Jessup (William Hurt, in his big-screen debut), who theorizes that experimenting with hallucinogens in an isolation tank can lead to physical transformation – evolutionary regression. The Timothy Leary-meets-2001 plot is based in part on the research of “psychonaut” John C. Lilly, who invented the isolation tank and did similar experiments in the 50’s and 60’s, though with less impressive results; in other words, a hole did not actually open in the fabric of space-time (though I suppose I can’t prove that it didn’t). In the film, Jessup’s increasingly risky experiments parallel his deteriorating relationship with his wife, Emily (Blair Brown); his obsession with isolation and stripping his life of all distracting clutter means terminating his marriage. After visiting a tribe of Indians in Mexico to find a holy entheogen that can trip him further than ever before, Jessup unlocks a key to his “primordial self.” His bone structure temporarily changes to something simian. On one trip, he actually becomes Primitive Man, and takes a trip to the zoo where he goes hunting for goats. On his next trip, he reverts even further, and that’s when things get really weird.

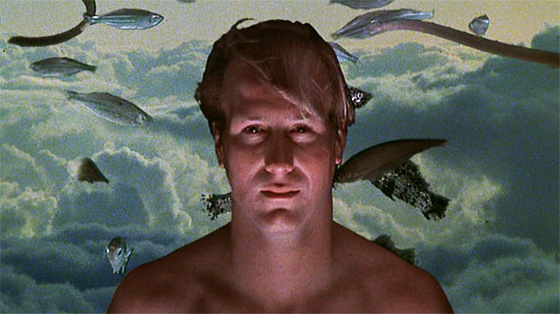

One of the isolation tank-induced hallucinations, as imagined by Ken Russell.

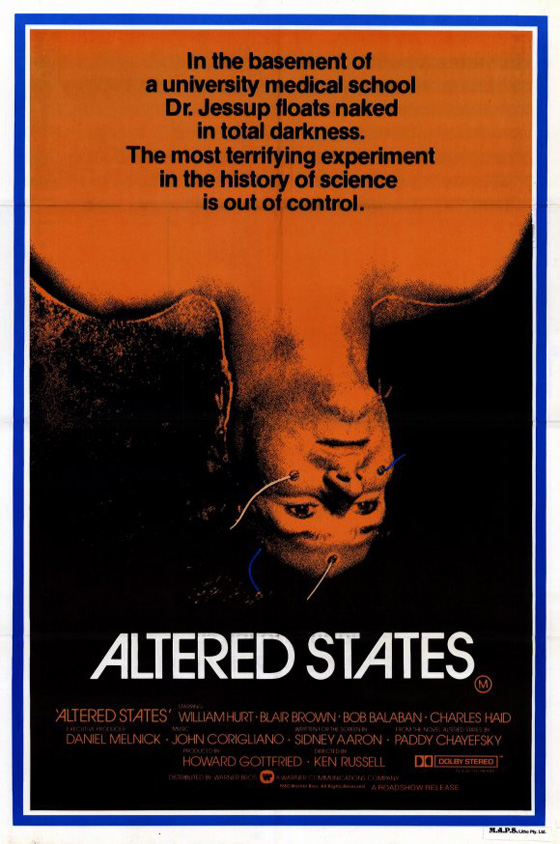

With its hallucinatory visual effects, grotesque makeup, and pioneering surround-sound design, Altered States was one of the wildest cinematic spectacles of the 80’s. And though it bears Ken Russell’s stamp, it’s unique in his filmography, very different from the flamboyant historical dramas he helmed in the prior decade. It was the first time the iconoclastic director was a gun-for-hire since his Harry Palmer spy film Billion Dollar Brain (1967). He accepted the project after the original director, Arthur Penn, walked off, reportedly following a dispute with the screenwriter, Paddy Chayefsky. Chayefsky was a creative force to be reckoned with, famous for his pioneering work on television, as well as the screenplays for The Americanization of Emily (1964), The Hospital (1971), and Network (1976); Altered States was adapted from his only novel, written in 1978. The two artists, having long since established their distinctive artistic voices, were destined to lock horns. Russell won the battle – Chayefsky took a pseudonym for the credits (actually his real name, Sidney Aaron) – but the director’s days in Hollywood were numbered. Russell would not make another film in the States until 1984’s Crimes of Passion, before returning to England to continue his filmmaking career, the budgets now smaller, the spectacle a little less spectacular.

Examining an unusual X-ray: Bob Balaban, John Larroquette, William Hurt, Charles Haid.

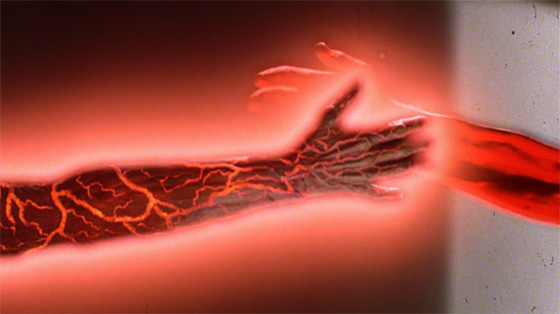

Supposedly one of Chayefsky’s complaints was that the dialogue (cluttered with technical and philosophical detail) was delivered too quickly. One wonders if he had ever seen a Ken Russell film before. The director’s favorite subjects were artists straining against the bonds of society and underappreciated by their contemporaries: Debussy (The Debussy Film), Tchaikovsky (The Music Lovers), and Wilde (Salome’s Last Dance), to name a few. One of his chief strengths as a director was channeling the imaginative energy of his subjects into the style of the film; in this regard, Savage Messiah (1972), about the sculptor Henri Gaudier, ranks as one of the most effective portraits of artistic fervor ever committed to celluloid. What is most surprising to me about revisiting Altered States, which I haven’t viewed in many years, is how the main character, a Harvard professor played by William Hurt, fits right in with all the misunderstood geniuses of Russell’s ouevre. If there is a fundamental conflict between the writer and director in the material, it is that Chayefsky wrote a film criticizing a man in love with isolation – his redemption is discovering human love in the film’s climax – but Russell has always been enamored by obsessive artistic explorers. In other words, Russell is not one to condemn Hurt’s cold-hearted genius, but to revel in it; which is perhaps why the emotional resolution, when Hurt finally reunites with his ex-wife, feels so tepid and unconvincing. Mind you, this denouement occurs after a climax in which Hurt transforms back and forth between his buck-naked self and a melting mutant, and Brown stumbles about their bedroom as a being apparently made of lava and starlight. I need to be careful not to accuse this film of conventionality.

Dr. Jessup paints the town red when he reverts to his primal self (played by Miguel Godreau).

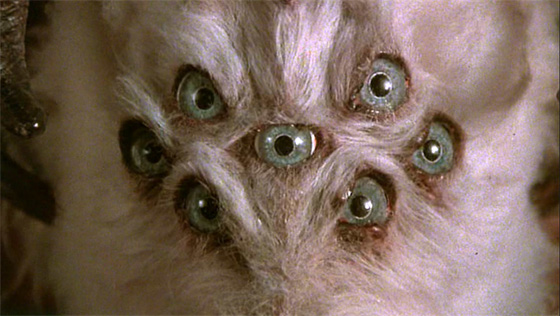

The crazy begins early, with some Catholic-themed hallucinations induced by Hurt’s time in the isolation tank: he witnesses naked bodies tormented in the fires of Hell, and a Satanic goat with many eyes being crucified, images that are kin with the dream sequences in Russell’s The Devils (1971) and Lair of the White Worm (1988). The Mexico scenes dial up the intensity of the strange images, including an eerily quiet scene in which the bodies of Hurt and Brown are overcome – and then swept away – by a desert storm. This moment in particular evokes the early Surrealist films of Luis Buñuel, Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L’Age d’or (1930); Russell cuts back and forth between the two bodies as the sand is blown away and the human forms slowly disintegrate, a visual evocation of the film’s theme of returning our selves to the dust that made us. The extended scene in which Hurt becomes an ape-man is less imaginative: as the creature stalks some security guards, then gets loose in the streets, the film becomes a much more typical horror movie. Granted, the sequence underlines the film’s ongoing Frankenstein motif, but the ape-man stuff takes the story’s philosophical concepts and makes them disappointingly literal. Our imaginations are grounded when the endless possibilities of Jessup’s experiments become one specific and tactile thing: a naked, hairy man who, to the modern eye, looks too much like one of those cavemen in the GEICO commercials. More exciting – however absurd – is the final transformation of Jessup, which finds us firmly in 2001 “Star Gate” territory, and Jessup’s Harvard lab turning into an actual primordial soup.

Emily (Blair Brown) is transformed by contact with state-changing Jessup (Hurt).

I think Chayefsky wanted a more cerebral film. The film is hectically paced, and the visuals do, at times, distract from the dialogue and its concepts: but perhaps Russell thought that an overloaded style was necessary to sell the audience on the credibility-stretching “externalizations” that Hurt undergoes in the film’s second half: right from the start, he establishes the film as a ride. Still, one can catch glimpses of what Chayefsky would have liked the film to have been, largely by watching the superb cast do their thing: in addition to Hurt and Brown, both of whom are excellent, the film features Bob Balaban and Charles Haid in strong roles as his skeptical – but ultimately indulgent – Harvard colleagues. The first half is undoubtedly the strongest, as we follow Hurt and his driven quest to uncover he-doesn’t-know-what, apathetic that his personal life has fallen to pieces; by the time the theories give results, and we see a hairy arm opening the lid of the isolation tank, the film switches into something else – possibly something regrettable, depending on your disposition. Altered States remains unique among the special effects extravaganzas of the early 80’s, and it’s a fun movie, but ultimately it falls short of its (vertigo-inducing) ambitions. In the film’s final scenes, you can see what it’s trying to do, while being removed from the experience you’re supposed to be having. And in this case, blame can be assigned to both Russell and Chayefsky.