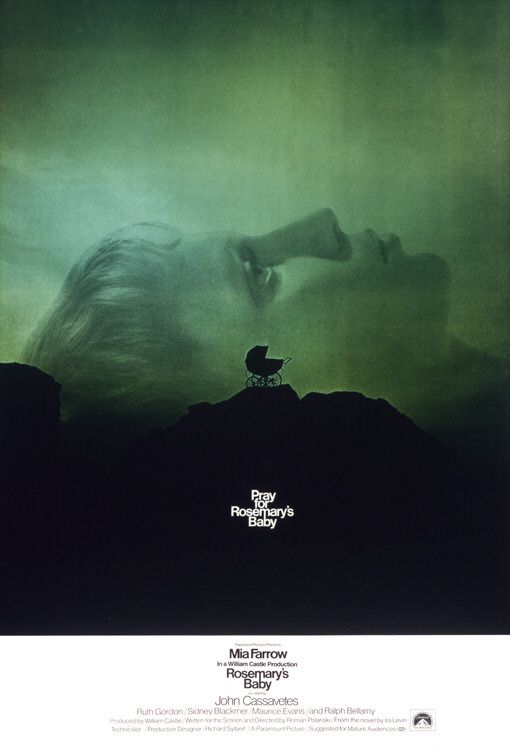

There is a key scene which sums up the whole of Rosemary’s Baby (1968). We are just over halfway through the film. Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow), who has been chalk-white, ruddy-eyed, and in physical pain since the start of her pregnancy, is upset that something is wrong with her child. She has just held a party with her friends, and in confiding to them, is more resolute than ever that she needs to get a second opinion from a doctor who was not recommended by her nosy next-door neighbors, the Castevets. In the aftermath of the party, she sits in a chair in the middle of a room, dirty dishes on the table behind her, the floor such a mess that it looks like a bomb has detonated, and her husband Guy (John Cassavetes), who was against the idea of the party from the start, paces angrily; “The thing to do now is move,” he mutters. “Guy,” Rosemary says, “I’m going to Dr. Hill Monday morning.” She repeats the concerns voiced to her by her friends, as though carefully recited; picking up on this, her husband calls those women “not very bright bitches,” and the argument quickly escalates to shouting. Guy has become strangely loyal to the Castevets, and Rosemary’s incredulity peaks when he offers a lame excuse for why she shouldn’t consult a different doctor than Sapirstein. “I won’t let you do it, Ro, because, uh – because it’s not fair to Sapirstein.” He can’t even look her in the eye as he says this. She suddenly rises and hovers over him, pencil-thin, blonde hair and white face and red eyes, as he cowers in his chair, the power suddenly shifted: “What are you talking about? What about what’s fair to me?” The argument continues, the struggle moves across the room. And finally she stops. The pain has subsided for the first time in months. She feels her baby kicking, and she is suddenly overcome with the wonder of carrying a life inside her, of being a mother. She knows her own body. The baby is okay. “It’s alive,” she says happily, in an eerie echo of another film’s famous line. She draws Guy’s hand to her belly to feel his unborn child, and he recoils and nervously retreats, his pitiful excuses now almost incoherent little phrases; “Don’t be scared, it won’t bite you,” she says.

Guy (John Cassavetes) and Rosemary (Mia Farrow): "It's alive, Guy, it's moving."

Famously, Cassavetes had a few rows with the film’s writer and director, Roman Polanski, whose first American film this was. Of course, Cassavetes was a groundbreaking filmmaker in his own right; his independent films were more freeform and improvisational, and one of his most influential films, Faces, would be released the same year. (I read an interview with Polanski some years ago in a magazine that was reprinting the script to Rosemary’s Baby. When asked what he thought of the then-recent The Blair Witch Project, the director responded that he liked the film, but that it was evidence of why you shouldn’t let actors write their own dialogue.) It is easy to see why the two directors would be at odds – and, poor Polanski, he had producer William Castle, originally slated to direct the film, hovering over his shoulder too, though he states they got on fine. Polanski plots his films painstakingly, much as Hitchcock did. Details are important. Blocking is important, and so is placement of the camera – what the camera sees and what it almost sees, like those famous shots in the film in which we peer around doorways to eavesdrop on conversations. His camera, in Rosemary’s Baby, is intensely subjective; it represents Rosemary’s gaze. With that gaze he likes to plant details that will pay off later. Just look at the initial elevator ride at the start of the film, as Elisha Cook Jr. takes newlyweds Farrow and Cassavetes to see the apartment on offer: Polanski’s camera takes particular note of the elevator operator, and then swings downward to mark that the elevator doesn’t stop evenly with the floor – the man has to manually adjust until they’re aligned. Unnecessary detail? No: later, in the film’s centerpiece dream sequence, we see the elevator operator steering Rosemary’s boat into a typhoon (“You’d better get below, Miss”); and in the climactic moment when she is being chased through the apartment building, she guides the elevator herself up to her floor, misses aligning it properly, and stumbles out face-first into the hallway as though that little gap were a steep cliff. Both of these moments emphasize the film’s nightmarish style.

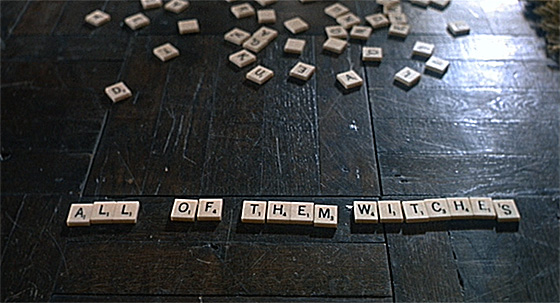

"The name is an anagram." Rosemary tries to decode Hutch's final message.

I find it easy to imagine this film as directed by either Castle or Cassavetes. Both directors had distinctive styles of their own. (Although thank God this film doesn’t have a “Fright Break.”) Castle wasn’t a bad director, and many of his films have genuine wit to them, but by as late as 1968 he was irretrievably typecast as a showman whose films leaned heavily on their gimmicks. He hadn’t the subtlety this film needed, and Robert Evans, newly appointed as Paramount’s head of production, insisted that Polanski would direct, impressed by his European thrillers such as Knife in the Water (1962) and Repulsion (1965), the latter another intensely subjective, hallucinatory horror film. Cassavetes would have been a more interesting choice than Castle. He had greater claims than Castle to being part of the New Hollywood, and though he seemed to despise this kind of pulpy genre material, perhaps at this stage of his career he might have invested himself fully in the project. There would be more hand-held shots, more exploration on the set, more input from the actors. It would have been a looser film, to be sure, and more raw. It may not have been superior to what Polanski pulled off – I strongly doubt that – but a Cassavetes-led horror film in the pivotal year of 1968 would have been a touchstone film of some kind, and is worth considering, even though we can’t be certain that Cassavetes ever would have considered it himself; he was never offered. It was only when he was on set that he began inserting his opinions, much to Polanski’s frustration.

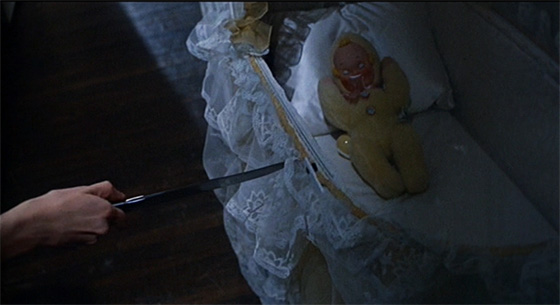

Rosemary on the prowl.

The after-party sequence I described is done in a single take, a virtuoso moment for both the director and the actors. It’s precisely designed and beautifully executed, but it’s easy to see why Cassavetes might have found Polanski’s style claustrophobic, his opportunities for exploration as an actor limited. Still, the confrontation between Guy and Rosemary Woodhouse is one of a handful of scenes in the film which can remind the viewer of a Cassavetes picture. Both he and Farrow let loose at one another in a way that we haven’t seen in the previous hour-and-twenty minutes; the film has been building toward this, as the newlyweds’ playful chatter and bedroom eyes have slowly given way to paranoia, isolation, and poisonous distrust. Later in the film, as Rosemary stumbles out of that elevator and locks herself in her apartment, frantically calling a friend for help while the barbarians are at the gate, we reach another moment than recalls the emotionally harrowing style of Cassavetes: suddenly Guy, Dr. Sapirstein, and friends of the Castevets are somehow inside her bedroom, and as the doctor prepares to inject her with a sedative, she explodes, screaming and raving, and they are forced to hold her down. Simultaneously, Sapirstein discovers she’s in labor. Here I cannot imagine Polanski directing very differently than Cassavetes. The horror in this horror film is never more clear, but it is rooted in the emotional betrayal of a loved one. Yet it took Polanski’s approach to give this moment such an impact: the rules, the structure, the fussiness and precision of his style are all shattered, such that the viewer can feel that a trap door has suddenly opened from below. Polanski – whose early shorts are every bit as jazzy as Cassavetes’ first film, Shadows (1959) – might be a controlling director, but he knows when to let go and unleash chaotic energy. That contrast lends the film much of its emotional force, and is part of the reason why the film has endured as a classic.

Rosemary’s Baby was issued on Blu-Ray last October as a spiffy Criterion edition. Extras are not carried over from Paramount’s prior DVD release – I’ll hang onto that, so I can keep the 1968 “Mia and Roman” featurette – but a new hour-long retrospective from Polanski, Farrow, and Evans is thorough and invaluable.