It is a struggle to extricate The Shining (1980) from its iconic moments – to properly “see” the film. It has taken me many, many years, and I am almost there, but not quite. Much of this is the fault of Stanley Kubrick, who had a damnable knack for creating “pure cinema” that would sear itself upon the cultural imagination; it is still difficult for me to understand that someone had to actually assemble 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) from scratch (source material notwithstanding); it is easier to believe that they were conceived out of a Star Gate to which only Kubrick had access. I have always hated – and deny – the concept of something being “ahead of its time.” All things are of their time, and it is more insightful to see how a work holds a dialogue with its contemporaries; but the films of Stanley Kubrick were certainly forward-thinking, and made great, risky leaps into untested realms. But in their accomplishments for the medium, the films became over-familiar, sectioned into clips that would play in every clip show. For The Shining, it was “Here’s Johnny,” it was the twins in the blue dresses asking Danny to come play with them, it was “Redrum,” it was the axe and the hedge maze and “All work and no play…” – and on and on. The first time I saw The Shining (as a teenager, on a VHS tape, shown to me by a friend who was already an acolyte of the film), I had two reactions. One was that I could only see those famous moments, so many of which I already knew from clip shows, and I couldn’t see how they all stuck together and formed a fluid story. The other was that it was scary as fuck.

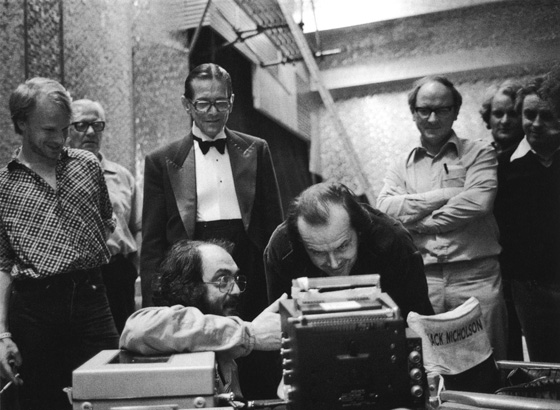

Behind the scenes at the Overlook Hotel: Joe Turkel, Stanley Kubrick, Jack Nicholson, and crew.

I warmed to it with subsequent viewings; whatever criticisms I had began to erode. Seeing it on the big screen, for example, accentuated the film’s hypnotic power. It means something to not be able to pause a film, to have it take up so much of your field of vision, to have it towering over you. I remember feeling the urge to look over my shoulder and down the aisle of the cavernous Oriental Theatre in Milwaukee, half-expecting to see a psychotic with an axe limping toward me. The film has a genuine effect of paranoia and choking dread. In anticipation of seeing Room 237 (2012), the documentary collecting conspiracy theories surrounding the film, I just rewatched The Shining to hold it fresh in my head. Even though I knew that was hardly necessary, because we all know The Shining and have it committed to memory, more or less. The only difference with this viewing is that it was on Blu-Ray, and the (excellent) high-resolution transfer creates a certain level of intimacy that I did not find on my old DVD. But, for whatever reason, I was drawn more into the narrative on this viewing, and in particular was able to better track the emotional lives – and psychic deterioration – of the Torrances. Yes, the story was fluid. Kubrick built his films with steel girders. The film holds up. Only the hammy “Heeere’s Johnny!” struck me as unnecessary. Why The Tonight Show? Why then? I suppose it doesn’t matter. Every home video release has the moment preserved on the cover, which says something for its popularity. You can’t argue with Kubrick, who knew what would stick.

Australian lobby card.

A strange thing happened to me this time around. While I was enjoying and admiring the craft of the film from the start, the acting seemed stilted or (as we know is the case) over-rehearsed. Unnatural. Jack Nicholson, as Jack Torrance, smiling sweetly during the job interview – the weird pauses between each spoken line during this scene. The over-politeness when the Torrances arrive at the Overlook, Barry Nelson standing stiffly while he delivers his lines, beaming at them – all of this, by the way, really no different from the acting styles of 2001, also much-criticized. Mind you, I didn’t have a problem with this – it’s Kubrick, it’s The Shining, we all know what we’re getting by now – but what I was not quite conscious of this time around was just how much I was being manipulated. As the film progresses, we see Jack’s slow decline. We have learned that he is quitting alcohol after injuring his son; we know his marriage is on shaky footing, and his wife and son are afraid of him. We can see that fear grow as Jack begins to snap at them. We see him staring off into space, possibly “shining” with the Overlook. We don’t know for sure just what he is anymore. At a key moment about halfway through the film, Danny Torrance walks into Room 237. We’re screaming at him to get back on his Big Wheel and peddle down the hall, but curiosity overcomes him. (And of course it does. After all, Hallorann – played by Scatman Crothers – had told the boy not to go in there. Which means that any boy then would.) Kubrick here makes a crucial decision. As Danny walks into the room, and we see the lights lit within and suggestions of the interior geography, Kubrick dissolves away. He withdraws at the moment of greatest dread (my recollection is that Stephen King showed what transpired within the room, but it has been many years since I’ve read the novel). The dissolve takes us to Wendy (Shelley Duvall) inspecting the furnaces and the power, checking to make sure all gauges are level – essentially reading the temperature of the Overlook, which is about to spike. She hears a disturbing screaming, and discovers her husband having a nightmare. We haven’t yet seen him so vulnerable. Those masks he has heretofore worn – the seemingly rehearsed dialogue, the insincere politeness, the demonic sarcasm – are suddenly gone. Panicked, he tells his wife that in his dream he chopped her and Danny into pieces. Danny enters the room, his collar torn, red marks on his throat; he’s sucking his thumb, in shock. Immediately Wendy turns on her husband, who remains recoiled; she accuses him of hurting Danny again, and takes her child safely out of the room. Jack remains alone, his face frozen stiff – as it has been before, and will be, permanently, in the film’s closing images. The world, it seems, has turned against him. His only ally is the hotel. Enter Lloyd the Bartender, ready to pour drinks. By now, Kubrick had me completely in his grip.

Wendy (Shelley Duvall) discovers that her son Danny (Danny Lloyd) has been injured, and blames her abusive husband rather than ghosts.

Really, it was Wendy that did it for me. Duvall plays Wendy as a complete wreck, pitiful and doe-eyed before Jack’s wrath, unable to confront him. In this moment, Jack’s most helpless, she glimpses the scope of his monstrousness and abandons him. Of course, she is both right and wrong. Jack Torrance is a monster, and for her and Danny’s safety, she should leave him posthaste. But we know Jack is innocent of this particular crime. Somehow, it’s possible for the viewer to be in sympathy with both Wendy and Jack; but, importantly, we understand what will now drive Jack back to drinking, and – an even greater leap – we can believe that now drinks will magically be available (and on the house). Consider that Kubrick has spent the previous hour drawing every element of the story to this one critical turning-point. Repeated images, monotone line readings occasionally interrupted by loud, abusive insults, sudden hallucinations (Danny sees visions of the twin girls and their dead bodies), not to mention the ominous, unnerving score (by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind with selections from György Ligeti, Béla Bartók, and Krzysztof Penderecki), all contribute to a feeling of dislocation and paranoia, which prepares us for the film’s second half, in which ghosts can not only appear but hold long conversations. But Kubrick is also setting up the real story of The Shining, which is a domestic horror story about alcoholism and abuse. (King was wrong when he claimed Kubrick failed to get this theme across.) In the moment when Wendy accuses her husband, credibly, of an injury to her son that was actually committed by a ghost, Kubrick achieves what all horror films should strive for: an emotional center derived from the horrors of everyday reality, accentuated by the supernatural/fantasy element. The haunted house genre should elevate the emotional theme of the story, and it does. So, yes, The Shining most definitely works as a cohesive story, and it has taken me a while to see it. And the film is still scary as fuck.