Two of Jean Rollin’s most fascinating experiments have now come to Blu-Ray courtesy Kino’s Redemption line. They may also be two of his best films. The Grapes of Death (Les Raisins de la mort, 1978) and Night of the Hunted (La Nuit de traquées, 1980) both have titles which recall other, completely different films (The Grapes of Wrath and The Night of the Hunter, respectively), but Rollin’s use of exploitation was never all that straightforward – and these are very unusual, even by his standards. They bookend one of his best-known efforts, Fascination (1979), and both feature that film’s star, blonde-haired Brigitte Lahaie, who had appeared in hardcore films and was making the transition to mainstream thanks to Rollin. The director had reluctantly made pornographic films to continue financing his own personal projects, for he was not a populist entertainer, and surreal, gothic, erotic, and psychedelic films like his Rape of the Vampire (1968) were never bound for either mainstream or critical success. Though he was undoubtedly an auteur, his artistic style was just a little too specific, appeal would always be limited, and his only commercial outlet – according to his financiers, at least – was going to be porn. Lahaie appeared in one of his pseudonymous efforts, Vibrations sexuelles (1977), and Rollin felt that the actress had potential for the mainstream, so he gave her a significant part in The Grapes of Death. Reportedly, much of the Grapes cast refused to associate with this actress from adult films, and wouldn’t speak to her on the set; nonetheless, Rollin went on to grant her leading roles in Fascination and Night of the Hunted. She would subsequently appear in more Rollin films, as well as other pictures like the horror film Faceless (1987) and Philip Kaufman’s Henry & June (1990), the first film to receive the NC-17 rating. Today she’s something of a sex icon in France, an author and the host of the radio show Lahaie, l’Amour et Vous. Rollin, meanwhile, would remain prolific but obscure, a marginalized cult filmmaker, until Redemption Films began introducing his oeuvre to a wider audience in the 90’s via home video releases. He was able to enjoy a minor revival before his death in 2010, just before Kino partnered with Redemption to introduce the director to an even wider audience via these handsome Blu-Rays.

A bloodthirsty Brigitte Lahaie leads two dogs on a hunt in "Grapes of Death."

Newcomers to the Rollin canon will inevitably pay extra (and undue) attention to spotty acting and unconvincing special effects; but Rollin aficionados will note the better-than-usual acting and a few scenes of notable FX, including a very convincing severed head. With a high-def transfer and Kino/Redemption’s usual sprinkling of extras, including insightful and thorough liner notes by Tim Lucas, the film is easier to appreciate for what it is: a macabre, dreamlike take on Night of the Living Dead (1968) filtered through the director’s haunted imagination. I watched this one a week ago for the first time, and the images and morbid tone have stuck with me to a potent degree. Technically, it is not a zombie movie, but a horror film about disease; one could as easily compare it to Romero’s The Crazies (1973) but for the telling, somnambulistic gait of the infected. So for all intents and purposes, it’s a zombie movie. But what a zombie movie! Rollin dials down his usual erotic elements – though they are present, as when Lahaie strips down (apparently in freezing cold temperatures) to prove she’s not infected. He emphasizes instead the nightmarish, almost stream-of-consciousness quality of the story, which follows a woman, Élisabeth (a riveting Marie-Georges Pascal), who finds herself stranded in a mountain village populated by psychopaths. The residents have consumed wine fermented from the local grapes as part of its annual Grape Harvest Festival, but the drink is tainted by a mind-and-body-altering pesticide. The chemical causes the skin to boil, burst, and decay, like some flesh-eating virus, and as the brain deteriorates, psychosis sets in.

Lobby card for "The Grapes of Death" featuring Mirella Rancelot as the blind, doomed Lucie.

As with Requiem for a Vampire (1972) and The Iron Rose (1973), dialogue is absent for long stretches, relying instead upon images – always Rollin’s strength. Élisabeth’s journey through this dark Wonderland begins as she’s riding with a friend in an eerily empty train into the mountains; when her friend leaves their compartment briefly, she’s murdered by one of the local grape-harvesters, who is the first poisoned by the pesticide, his face leaking blood and goop. He then walks down the aisle of the passenger train and takes a seat in the compartment next to Élisabeth: a scene which is a minor masterpiece of polite awkwardness, as the poor girl tries to ignore this unwelcome, unpleasant intruder, until finally she realizes that his face is starting to melt right off. So begins her journey – fleeing into the village where she meets some bizarre characters, the first being a beautiful blind woman, Lucie (Mirella Rancelot), whose eyes are pupil-less contact lenses that bring to mind The Plague of the Zombies (1966), though, ironically, she’s one of the uninfected. Lucie is searching for her guide, but the man has consumed the wine and begun to transform – something which she can’t perceive through her blindness. “Je t’aime, Lucie,” says the man after killing the poor girl, fulfilling his unrequited love with a kiss only after severing her head from her body, which has been nailed to a door. More horrifying is the parade of villagers who follow him through the streets, chanting “Je t’aime, Lucie,” in a hollow echo. Vintage Rollin.

Élisabeth (Marie-Georges Pascal) reunites with her fiancé Michel (Michel Herval), whose body is transforming from the poisoned wine.

More ingenious is the character played by Lahaie, a beautiful woman occupying the mayor’s manor in a white nightgown and a too-happy smile. Her body bears no signs of corruption, but, as with the character she’d play in Fascination, her physical beauty disguises a dangerous madness within. She betrays Élisabeth to the village, then leads the hunt when she escapes, in one hellish scene pulling two black dogs by a leash past a burning cottage. Her end, poetically, comes as she rages at the disintegration of her porcelain face – her corruption finally made physical. All this is foreshadowing for Élisabeth’s reunion with her fiancé Michel (Michel Herval), the White Rabbit she’s been pursuing all along. Michel is responsible for the pesticide, and though he’s been infected, he’s managed to keep hold of his rationality for just a little while – long enough to confess to his lover and ask for absolution. Just when you see where this is going, Rollin adds a twist – one tied into a final, macabre image which is one of those that’s stuck with me so vividly this past week.

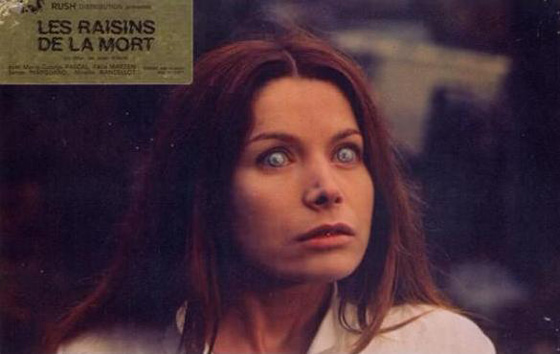

Lahaie as the lost Élisabeth in "Night of the Hunted."

There is a different Élisabeth in Night of the Hunted (1980), and she is now played by Brigitte Lahaie. As with the protagonist of Memento (2000), she lacks the ability to create permanent memories. We meet her as she emerges from the woods, running from something (she can’t remember what), and rescued by a passing driver, the young, handsome Robert (Vincent Gardère). The opening is rich in Grimm’s fairy tale overtones – the black forest, the lost girl – and it becomes all the more Jungian when we glimpse a naked woman (Dominique Journet) kneeling in the woods calling out to Élisabeth, unseen and unheard as the car drives off. The fairy tale feeling continues when Élisabeth is abducted by two mysterious strangers and taken to a place which is only referred to as “the black tower.” The building of steel and glass is a kind of mental institution, but all of the patients share Élisabeth’s strange affliction: a worsening amnesia. The rooms and corridors are lacking in decoration, cold and soulless. One of the attendants is a serial rapist, exploiting his power over women who can never find their way back to their rooms, and won’t be able to remember that they were raped. Élisabeth is told that she’s been here before, and is “reunited” with her roommate Catherine (Catherine Greinier, aka hardcore performer Cathy Stewart, another marginalized exile entering the Rollinverse). Catherine not only suffers from amnesia, but also a lack of motor control, and can barely feed herself. One of the more fascinating moments in the film comes when Catherine invents a past for herself and Élisabeth, “old friends” – breaking into tears as she pleads for the vacant-eyed Élisabeth to confirm her false memories. One is reminded of Rachel’s struggle with her invented past in Blade Runner (1982).

Amnesiacs Élisabeth and Catherine (Catherine Greinier) explore the "black tower" in "Night of the Hunted."

Indeed, science fiction elements begin to intrude upon Night of the Hunted as the plot gradually reveals itself. The amnesia, we learn, is an illness brought on by a disastrous radiation leak. The infected were brought to the “black tower” as part of a government cover-up of the incident. With overtones of the Holocaust, the ultimate fate of each patient is to be taken aboard a train and shipped off to be exterminated. But all that knowledge comes later. Night of the Hunted, like The Grapes of Death, is firmly fixed to the POV of its Élisabeth. She falls in love with Robert, and spends the rest of the film looking for him, even though her memory is fading fast. When she is discovered in the institution by that girl we glimpsed naked in the forest, we see the happy recognition in Lahaie’s eyes – elated to discover that someone is familiar, even though she doesn’t know why or who this person truly is. All of this leads to one of the most powerful endings in Rollin’s filmography, a beautiful image married to a tonally-perfect metaphor. But it comes attached to an imperfect film; such are the pangs of being a Rollin fan. Gratuitous sex scenes, forced upon the director by the money-men, go on for too long and compromise the film’s higher intentions. It’s an exploitation movie bowing to “commercial” interests, and women doff their clothes for no other purpose than the demands of the market. To keep the budget low, Rollin reportedly shot the film in seven days, a Corman-esque feat that, thankfully, doesn’t hurt the film too much. The important thing is that enough of Rollin’s sensibility pushes through to make this a truly memorable B-movie, one that’s strangely touching. It’s compelling evidence that Rollin and Lahaie could transcend the seedy industry that fed them, and produce something with more than a passing resemblance to Art.