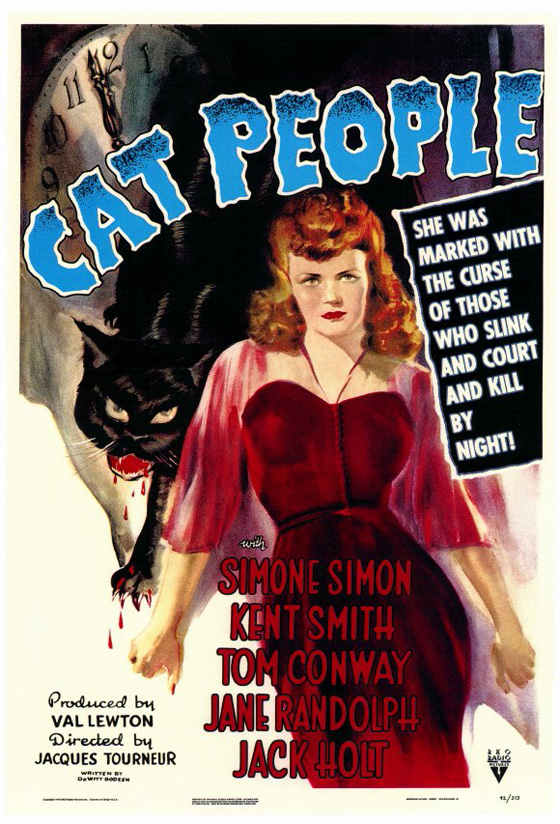

In certain ways, the Hays Code was a boon. Beginning in 1934, all Hollywood films had to obtain content approval via the Motion Picture Production Code, but although it’s certainly eye-opening to watch many of those scandalous “Pre-Code” films, it was not the end of cinema for adults: witness Cat People (1942) from producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur, one of the most truly adult films of the 1940’s. It’s not that it is explicit. There is no on-screen sex and little violence, but without those distractions the themes flourish. With surprising maturity it portrays a marriage coming to pieces through mistrust, isolation, and – most of all – fear of intimacy. Its poster portrays Simone Simon in a blood-red dress accompanied by a panther with blood dripping from tooth and paw; above the title – chosen by RKO, not by Lewton – hovers a clock about to strike midnight, as though to imply that is what will cause this woman to transform into a deadly animal. That’s not quite accurate. Passion will enact the metamorphosis. The real subject of this horror film is the marriage bed.

Irena (Simone Simon) shows Oliver (Kent Smith) her statue of King John of Serbia, cat-impaler.

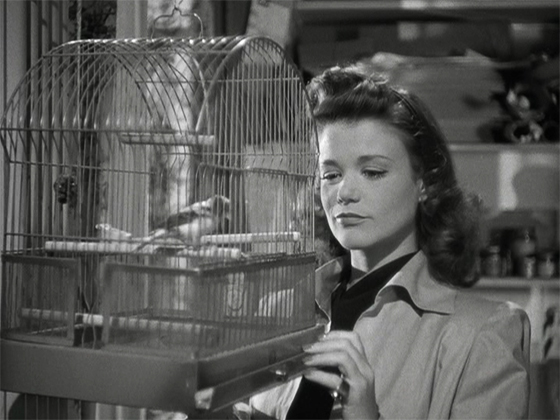

It all begins so happily, like a breezy romantic comedy with only a few ominous signs here and there. A beautiful Serbian immigrant, Irena (Simon), is sketching a panther at the zoo, and a handsome man flirts with her. That man, played by Kent Smith, is coincidentally named Oliver Reed – no relation to the better-known actor who would, almost two decades later, transform not into a cat but a wolf (The Curse of the Werewolf). After they leave, the camera follows her discarded sketch as it drifts with the leaves and finally settles against a wall: disturbingly, she has drawn the panther impaled by a sword. Irena and Oliver quickly become a couple, despite further unsettling signs. She has a statue of King John of Serbia, Jovan Nenad, impaling a cat upon his sword, and she tells a story of the 16th century figure driving out Satan-worshiping witches from the land, people who had the ability to transform themselves into cats. He buys her a cat, but it hisses and won’t go near her. He replaces it with a bird, which she finds herself pawing at in its cage, until it dies of fright. She continues to pay visits to the panther, keeping an eye on the key to its cage, poorly guarded by the zookeeper. Despite the fact that they have never kissed – Irena is unusually reticent – they are wed. Their wedding banquet at a cafe called The Belgrade is interrupted by a mysterious woman dressed entirely in black who calls Irena “my sister” in Serbian, and the bride is mortified. That night, she closes the bedroom door on her groom. “I want to be Mrs. Reed…but I want to be Mrs. Reed really. I want to be everything that name means to me, but I can’t, I can’t. Oliver, be kind, be patient. Let me have time, time to get over that feeling there’s something evil in me.”

Irena plays with her pet bird.

The easy-going Oliver, it turns out, has vast reserves of patience, but every man has his limits. Growing closer to his co-worker, the smart and sassy Alice (Jane Randolph), he begins to share his unhappiness; when she recommends that Irena see a psychiatrist, Irena feels betrayed. Oliver says that Alice is “such a good egg she can understand anything,” to which Irena responds, “There are some things a woman does not want other women to ‘understand.'” Spiraling into jealousy, but still mortified that physical intimacy with her husband might cause her to change into a beast, she begins stalking Alice. This leads to two justifiably famous sequences of suggestion, shadows, sound, and terror. In the first, Alice walks down an empty street at night while Irena follows from a distance. At first we hear Irena’s sharp footsteps quickly approaching. Then they suddenly stop. Alice glances behind her and sees the gradual bend of the sidewalk, the street lamps, and nothing else. She continues to walk. Suddenly we hear what sounds like the beginning of a panther’s growl, very close, which fuses with the squeal of a bus skidding to a halt in front of her; for a moment our senses are fooled into thinking that the screaming animal has pounced.

The Other Woman, Alice Moore (Jane Randolph), is stalked on a lonely street at night.

The second moment comes when Alice decides to take a swim in an indoor pool (again, at night, and with the lights turned down). After she’s left for the locker room, we see Irena arriving at the front desk and being given directions to the pool. Alice has just changed into her swimsuit when she hears a growl and sees the shadow of something low creeping down the stairs. To escape, she plunges into the pool and swims to its center, and Tourneur’s camera moves in close as she treads water, her face just above the surface, panting for breath as feral sounds echo throughout the room, and a strange shadow moves along the wall. She screams, the lights are flipped on, and Irena is standing there, smiling with kind menace. These two moments have become textbook examples of what horror can do through implication rather than explicit expression – and they’re still terrifying. But the film, at a lean 73 minutes (to meet RKO’s requirement that Lewton’s horror films run no longer than 75), is stuffed to bursting with moments of low-budget invention. After a panther (escaped from its cage, or Irena herself?) slaughters some lambs in the zoo, a scene to which John Landis would pay homage in An American Werewolf in London (1981), the camera tracks bloody paw prints along the street as they seamlessly transform into the prints of high-heeled shoes. Scene transitions frequently use a feline theme, extending even to a close-up of a model ship’s cat-shaped figurehead. Oliver and Alice’s workspace is transformed at night into a realm of deadly shadows, assisted by the eerily-glowing lights of their desks, setting the stage for a tense stand-off with the panther. A dream sequence, weighted by fashionable Freudianism, contains scattered surreal images but also eye-catching cel animation of slinking cats. A climactic showdown between Irena’s smitten psychiatrist, Dr. Louis Judd (Tom Conway of the Falcon series), and the panther is played entirely through shadows cast against the wall, as he battles the beast like the Serbian King John, wielding a sword hidden in his cane.

Tom Conway as Dr. Louis Judd.

Tragically, Irena Dubrovna never gets to overcome her apprehension of sexual intimacy, but, as we’ve learned by the film’s climax, fears of her ethnic heritage were well-founded. What’s more surprising is that a film of 1942 is willing and able to tackle such matters at all. The film is sophisticated enough in its treatment of the touchy material that lifting the Hays Code would not have made it any more of a perfect work of art than it already is (certainly Paul Schrader’s spell-everything-out remake from forty years later could not improve upon it, though I’m probably overdue for a second viewing). Cat People became the flagship film of a short-lived horror renaissance from Lewton courtesy his contract with RKO: an exceptional and utterly unique genre franchise that lasted from 1942 through 1946. Each of his films borrows the expressionist use of lighting from the early Universal horror films while running far from any “monster mash” temptations. He was given free reign to apply the horror genre to his pet themes of mental illness, suicide, depression, and a Poe-like obsession with death – just so long as he kept the running times short and used the titles RKO supplied. (The best example of this is the second film of the series, 1943’s I Walked with a Zombie, whose sensationalistic title does not begin to suggest the poetic brilliance of the film’s content.) No wonder that in the latter half of the series Lewton would join forces with none other than Boris Karloff, who was dismayed at the direction Universal had taken. Tourneur would make a couple more films for Lewton, including the similar The Leopard Man (1943), before moving onto other projects such as the film noir classic Out of the Past (1947) and the Lewton-esque horror/noir hybrid Night of the Demon (1957). When Lewton was obliged to provide a follow-up to the very profitable Cat People, he delivered one of the most unconventional sequels ever made, Robert Wise’s The Curse of the Cat People (1944), a children’s film with fairy tale overtones. Meanwhile, Tom Conway’s Dr. Judd reappeared in the extraordinary The Seventh Victim (1943), directed by Mark Robson.