Midnight Only is a proud participant in The William Castle Blogathon: Scaring the Pants Off America (July 29th-August 2nd, 2013), presented by The Last Drive In and Goregirl’s Dungeon.

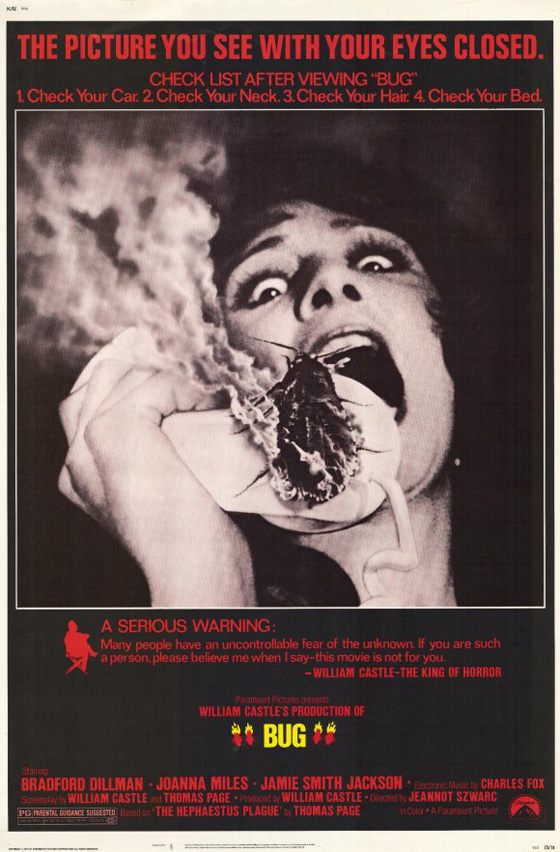

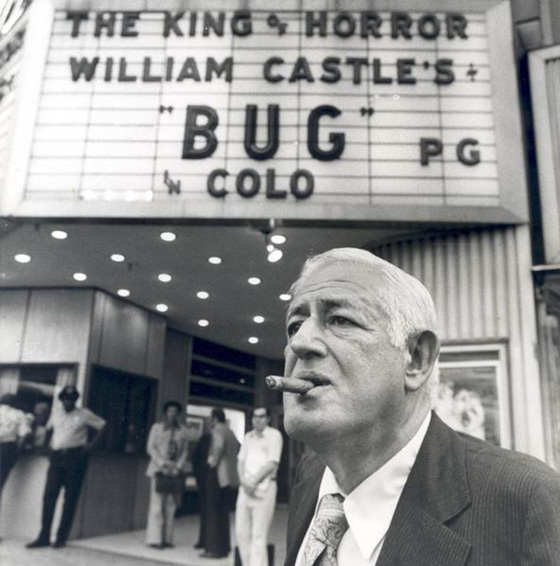

The times were catching up with William Castle, in more ways that one. His unusual horror film Shanks (1974), starring Marcel Marceau, failed at the box office with no help from an unenthusiastic Paramount; in declining health, he decided to take a step back from directing. His next film would be a retreat to the audience-pleasing exploitation that made his name. Alas, released the same month was Jaws (1975), a film that was to cinema the kind of seismic event depicted onscreen in the opening minutes of what would be Castle’s last effort, Bug (1975). Castle’s film made its money back, but naturally it was eclipsed in the wake of Spielberg. Some adapted quickly. Bug‘s French-American director, Jeannot Szwarc – who was using the film to graduate from television gigs like Night Gallery and Marcus Welby, M.D. – would land Jaws 2 (1978). Bug‘s star, Bradford Dillman (The Way We Were), would move on to the best of the Jaws knock-offs, Joe Dante’s Piranha (1978). As for Castle, he prepared the story of a haunted apartment complex for MGM, to be called 2000 Lakeview Drive (“An Address of Extinction”), but the project fell apart. He died of a heart attack on May 31, 1977 – closing the door on a golden era of schlock films and good-natured hucksterism.

Professor Jim Parmiter (Bradford Dillman) communicates with a squirrel during a classroom demonstration.

The good news about Bug is that it’s not exactly what you’d expect. That, and the fact that Castle – who co-wrote the screenplay with Thomas Page, adapting Page’s novel The Hephaestus Plague – gets the action moving quickly; if there was one thing Castle cared about, it was making sure no one got bored. Quite a lot is packed into the film’s 99 minutes, from that opening earthquake (which tears a church to pieces while the worshipers run screaming through the aisles) to the introduction of the film’s stars, Madagascar hissing cockroaches (!), and through the story’s multiple permutations. A giant crack opens in the earth beneath Riverside, California, and out pours smoke and a host of large cockroaches with shells “like steel” and rear antennae that, when rubbed together, can ignite flame. Surely it’s no coincidence that the film opens with images of churchgoers singing hymns and ends with images of Hell: that chasm lit by a pulsating red glow, more and more roaches swarming forth. With another low budget, Castle delivers the Apocalypse in microcosm, witnessed through the eyes of one man – university professor Jim Parmiter (Dillman) – who grows increasingly unhinged as his experiments on the roaches progress. The film’s opening half, as the “fire bugs” wreak havoc on Riverside, might lead the viewer to expect an Irwin Allen spectacle for its finale; instead, the film becomes more intimate and strange as we lock ourselves into a remote house with Parmiter and his bugs. He breeds them. He tries to communicate with them, just like he does with a squirrel earlier in the film. Eventually, they talk back, in their own way…we’re suddenly moving into the bizarre realm of Phase IV (1974).

Carrie Parmiter (Joanna Miles) discovers the danger of hairspray.

Along the way are scattered shocks, some fairly effective, all of them delightfully ludicrous. After a pet cat is killed by one of the bugs, student Gerald Metbaum (Richard Gilliland) places its mutilated corpse in a box and shows it to Parmiter in the cafeteria while the poor guy’s trying to eat his lunch. In another scene, the camera reveals one of the roaches clinging to a phone, which then rings; the woman who picks it up gets her ear burned in bright flashes before blood starts oozing out. And Parmiter’s wife (Joanna Miles) meets an unfortunate end in the Brady Bunch house (the same set, reportedly), as one of the critters sneaks into her hair and sets her head ablaze. Later, when Parmiter goes to a secluded house to breed and experiment upon the roaches, they just won’t stay in that box of his, pushing up the lid to crawl out, and developing a taste for meat – first some raw steak sitting on a plate, and then Parmiter himself, biting into his chest while he sleeps. (Why he never places a lock on that box is a mystery.) Also worth noting: the roaches’ preferred method of killing is blowing up people in cars, Mafia-style.

Parmiter discovers his new breed of roaches enjoy the taste of human flesh.

After what seems to be an anticlimax – the roaches begin to die, unable to adapt to the lower-pressure surface world – Bug kicks into a different gear. The manic-eyed Dillman, looking increasingly gaunt (and increasingly bearded), decides to revive a captured specimen in a diving helmet with a pressure gauge, cross-breeding the roach and creating a race with a stronger chance of survival. By the film’s end, he is so simpatico with the roaches that they begin spelling out words on the wall, scurrying into place and forming first his name, then the letters he calls out (“Y…Z!”), like some particularly strange episode of Sesame Street. Following the killing of the visiting Patty McCormack (the Bad Seed herself), Parmiter confronts the creatures’ latest horrifying metamorphosis – they finally have wings.

William Castle in 1975

Castle had one last irresistible gimmick in mind, in the tradition of House on Haunted Hill (1959), The Tingler (1959), 13 Ghosts (1960), and all the other films that made his name so famous: he intended to install “Roach Seats” in the theaters. Not too dissimilar to the Tingler‘s “Percepto” device, this would be a mechanism like a windshield wiper that would be installed below the seat, tickling the audience members whenever cockroaches scurried across the screen. Paramount, which was wrapping up its contract with Castle, balked at the expense. He had to settle for a more scaled-down bit of publicity: a million-dollar insurance policy on one of the film’s stars, Hercules the cockroach. It’s a shame, as the Roach Seats could have been a last, nostalgic bit of William Castle showmanship, and given the experience of watching Bug a considerable entertainment boost. His idea might be even more welcome today. With the rising interest in “4D” theaters – the audience experiencing physical effects such as moving seats, a spray of mist, blowing wind, and so on – along with the current popularity of 3D and IMAX, film as an enveloping entertainment experience is becoming the standard. The movies, it seems, are now a William Castle world.