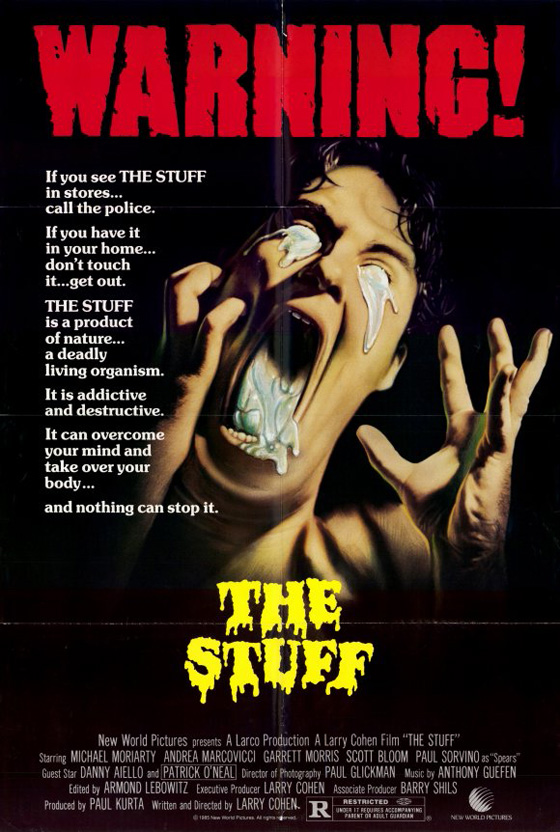

“Are you eatin’ it, or is it eatin’ you?” asks a cynical Michael Moriarty at the end of Larry Cohen’s The Stuff (1985), and that’s the plot in a conveniently-packaged cardboard carton. For his thirteenth directorial effort, Cohen, the man behind It’s Alive (1974), God Told Me To (1976), and Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), once again proved he could deliver on an absurd but irresistible premise. What if a new kind of food swept the nation, ubiquitous, filling up the aisles in grocery stores, franchising out like Krispy Kreme or TCBY at their zeniths, clogging the airwaves with flashy commercials replete with Abe Vigoda and breakdancing? What if the white, gloopy product was so addictively delicious that as soon as you taste it, you can’t stop eating it? And even though its packaging boasts that it contains no artificial ingredients, not even the distributor knows where it comes from or what it is. Thus its name: The Stuff. As its commercial jingle goes, “Enough is Never Enough” – an appealing slogan, but one that doesn’t exactly deny Moriarty’s more blunt statement. Are you eating it, or…?

A fashion shoot for a Stuff ad campaign.

Moriarty, who starred in Q and has periodically reunited with Cohen over the years, plays David “Mo” Rutherford, an industrial saboteur hired by an ice cream manufacturer to investigate The Stuff, which is wreaking havoc on the dessert industry. One exec justifies their hiring of a spy with a resigned “I suppose we do have to keep the world safe for ice cream.” The cocky, Southern-fried, smooth-talking Rutherford, an ex-FBI agent, finds some unusual allies in his quest: Nicole (Andrea Marcovicci, The Hand), an advertising whiz who branded The Stuff and falls for Rutherford’s quirky charms; Charlie Hobbs (Saturday Night Live‘s Garrett Morris), founder of the Chocolate Chip Charlie chain (a thinly-disguised parody of Famous Amos Cookies); Colonel Spears, an unhinged right-wing militant who has no trouble believing their conspiracy theories (Paul Sorvino, channeling Sterling Hayden’s Jack D. Ripper from Dr. Strangelove); and a young suburban pre-teen named Jason (Scott Bloom), who suspects The Stuff is nefarious after witnessing it moving around inside his fridge, and watches as his family gets taken over, Body Snatchers-style. As they become more insistent that he be a good boy and eat The Stuff, he finds himself taking extreme measures, such as substituting shaving cream and wincingly swallowing it down; and going on a rampage at the local grocery store to destroy its aisles and aisles of Stuff cartons.

Mo Rutherford (Michael Moriarty) and Nicole (Andrea Marcovicci) discover the source of The Stuff.

So what’s so nasty about The Stuff? The gloop has a life of its own, bubbling, frothing, and shooting at its victims, in one scene lifting a man off the ground and pinning him against the wall and ceiling. Apparently it doesn’t digest very well: those who consume it eventually find themselves controlled like puppets, and when it leaves their bodies – via a gaping, unnaturally-wide mouth, “It sort of – vacates the premises when it’s through,” as Chocolate Chip Charlie puts it. The bodies are left as dry, empty husks. The only antidote seems to be fire, which Nicole learns when The Stuff covers Mo’s face, suffocating him, and she decides to just light his face on fire to burn it off. For a low-budget New World production, The Stuff delivers some inventive special effects: in certain shots the goo seems to be defying gravity as it pours forth in all directions, evidently achieved by creating sets tilted at extreme angles. Interestingly, among those who worked on the film are two icons of stop-motion animation, Jim Danforth and David Allen, though the most memorable effects involve mechanical heads that expand grotesquely and explode. The true source is a fissure in the earth from which The Stuff comes bubbling up, and in the film’s money shot we witness a mining company surrounding a large white lake from which strange geysers rise slowly upward, like slimy fingers reaching into the air. Cohen does a nice job of stretching his budget to present a sense of scale for this semi-apocalyptic film, but most of this is achieved with his script that often plays like a 70’s political thriller, as Rutherford interviews key suspects (including FDA exec Danny Aiello, in a creepy scene with his Stuff-hungry dog) while evading gun-toting “Stuffies.”

The Stuff "vacates the premises."

As for the satire, it’s naturally woven into the narrative and the imagery. When a Stuff restaurant is destroyed, Cohen frames the shot so we can see the McDonald’s planted right next door. The grocery store where young Jason goes berserk is contaminated everywhere by Stuff products and Stuff advertising. The commercials, integral to our understanding of how pervasive the product’s reach has become, are convincingly enthusiastic and over-the-top (typical of 80’s TV ads, anyway), and Cohen even squeezes in a “Where’s the Beef?” nod (“Where’s the Stuff?”). Decades after the film’s release, in a post-globalization world with greater sensitivity and alarm about what’s lurking on our grocery store shelves, The Stuff seems even more relevant. (I see little Jason, attacking his supermarket with a baseball bat, as a budding Michael Pollan. Eat local!) The film’s great fun, but it would be a mistake to single it out as completely unique among 80’s horror films. It arrived at a time when slasher films were beginning to overstay their welcome, and directors who grew up on 50’s and 60’s horror and science fiction started to pay overt homage to their inspirations. Just as The Stuff owes much to The Blob (1958) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), Cohen was not alone in looking backward. Tom Holland’s superb, nostalgic Fright Night was released the same year. John Landis had given us his spin on The Wolf Man with An American Werewolf in London (1981); Tobe Hooper paid tribute to Hammer with Lifeforce (1985), and would soon be remaking Invaders from Mars (1986); David Cronenberg would remake The Fly (1986); and even The Blob would be revived (in 1988). As for its satirical intentions, The Stuff compares well to John Carpenter’s They Live (1988), and bears a striking resemblance to the much-loathed (at the time), greatly underrated Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), with its similar characters investigating another sinister commercial plot, this one involving Halloween masks. But I’d much rather rewatch ads pitching the foamy, evidently-delicious The Stuff than the deliberately-maddening “Silver Shamrock” campaign featured in Tommy Lee Wallace’s film. I can’t get enough of The Stuff.