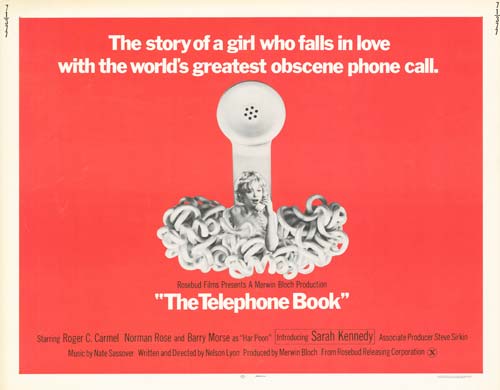

The tagline says it all: “The story of a girl who falls in love with the world’s greatest obscene phone call.” That didn’t sell many tickets – despite the fact that the film was produced by Merwin “Merv” Bloch, New Yorker and ad man whose lengthy resumé in advertising includes working on the poster campaign for 2001; and despite the fact that one of the film’s stars – the obscene caller himself – is the legendary, dulcet-toned Norman Rose, whose nickname was “The Voice of God,” and here appears in a pig mask while describing his life story from between a girl’s open legs. The Telephone Book (1971), intended as a low-budget R-rated film that went over-budget and X-rated, didn’t do anyone any favors. Rose reportedly lost some of his big contracts due to his association with the film. Bloch hoped that Hugh Hefner, who loved the film and screened it at the Playboy Mansion alongside Gimme Shelter (1970), would release it as the flagship title for Playboy Productions, but Hefner instead reached for a higher brow: Roman Polanski’s grim and bloody Macbeth (1971). Nelson Lyon, the film’s writer-director and a veteran of Andy Warhol’s Factory, hoped the film would launch a career, but despite Warhol’s fleeting involvement with The Telephone Book (he appeared in a brief “intermission” scene which was cut, and loaned out some of his starlets for cameo appearances), the film received little attention and mostly poor reviews. Lyon (who passed away in 2012) found himself a writing job at Saturday Night Live; and his later career was overshadowed by his involvement in the final days of John Belushi’s life (Lyon was given the same speedball that killed his friend). The Telephone Book was largely forgotten, until revival screenings in recent years which culminated, finally, with a new Blu-Ray/DVD release from Vinegar Syndrome, the fledgling label that’s also released the excellent documentary A Labor of Love (1976).

Alice (Sarah Kennedy) takes a call during an orgy hosted by Barry Morse.

The Telephone Book concerns Alice’s pursuit of a white rabbit who turns out to be a man in a pig mask. Living an empty life in a New York apartment wallpapered with dirty pictures, Alice (Sarah Kennedy, recruited from TV commercials and perfect in the role) receives a spiritual awakening when she receives a call from a man who calls himself “John Smith.” When she asks to meet him face-to-face, he invites her to look him up in the phone book, which leads her to strange encounters with impostors eager to take advantage of her sexual openness. Her final, extended, and completely surreal encounter with the real John Smith contains no physical contact and quite a lot of talking. The movie could only have been made in its particular era: floating in the wake of New York’s underground film scene (with its more groundbreaking pictures, including Warhol’s), but preceding the X-rating as a flag for pornography (there’s nothing hardcore here). Nonetheless, it’s clear to see why the film failed to connect with those few who would want to go see a film about a woman who falls in love with an obscene phone call. It’s neither this nor that: an oddity that was destined to escape down the cracks. The film is a satire with an irreverent, profane tone similar to Robert Downey’s Putney Swope (1969); it’s surreal and dream-like, established with its Alice in Wonderland structure; but it’s more sex-obsessed than the average art house film, with abundant nudity and an orgasmic ending featuring animation that’s both abstract and explicit. But the film has a rather European sense of ennui. What sex the film contains is Mad Magazine-broad, including an orgy sequence featuring a number of naked women stacked uncomfortably on top of The Fugitive‘s Barry Morse, playing a man who wants to become the Orson Welles of stag movies (when Alice is invited to participate, she can find little to do except awkwardly remove Morse’s fuzzy black sock).

The smitten Alice meets her obscene caller (Norman Rose), who refuses to touch her.

The black-and-white photography by Leon Perera is often lovely to behold; to indicate the transcendence of one final obscene phone call, the final sequence, initiated by animator Leonard Glasser’s dirty little cartoon, switches suddenly to color, providing a nice visual jolt. Avant-garde experimentation enlivens the proceedings – again, nothing groundbreaking, but constantly subverting any expectations that this is a blue movie. Some of Rose’s seductive dialogue is rendered in subtitles rather than through sound (by necessity, apparently: Rose wasn’t around to loop his lines), and the film is frequently interrupted by confessionals to the camera by everyday people, expressing why they decided to become obscene callers. One self-described “steady guy” says, “Now I don’t feel the need to make obscene phone calls anymore. You see, I know that the world is going to come to an end in a year because of the violent emergence of Atlantis and the coming of little green men with the scorching white light of Mu, and this secret knowledge has given me the peace I need to develop a regular sex life.” Rose’s final monologue, in which he describes a psychological breakthrough during a weightlessness test at Cape Canaveral, is appropriately cosmic and deranged; Lyon films his pig-masked face against various female body parts during the long speech, until his face spins into the cosmos and melts into a starfield.

Alice, satisfied at last.

Though it’s no lost masterpiece, what sticks with me is the strange conviction and commitment of the cast. Lines are spoken rapidly, declaratively, with clenched jaws and glazed eyes. (An argument could be made that the whole film is like a dirty soliloquy made by veterans of advertising about advertising. Advertising, obscene calls – same difference.) What lingers is Morse, piled under those women, stating that his new stag film will be “a bold modern statement of the condition of man,” while breasts dangle above his stern face. (And Alice’s hilarious line delivery of “What’s the plot?!” – which makes the whole film worth seeing once.) What lingers is Roger C. Carmel (Star Trek‘s Harry Mudd) lasciviously working his change-maker belt to pay for every second of Alice’s awkward tale of a man with priapism (familiar character actor William Hickey, humorously bored as he tells his tale of woe to the camera). What lingers is that final image of Alice in the phone booth, the sun having risen, sexually satisfied and now asleep at the phone, an ending both sweet and melancholy. Perhaps The Telephone Book was prescient; it speaks to our current, disconnected era of virtual sex. It has an authentic loneliness. It’s telling that when Alice ventures out of her apartment, seeking an actual one-on-one connection with another human, she scares off the flasher she encounters when she tries to reciprocate. It’s one thing to lust. Real connection is scary.