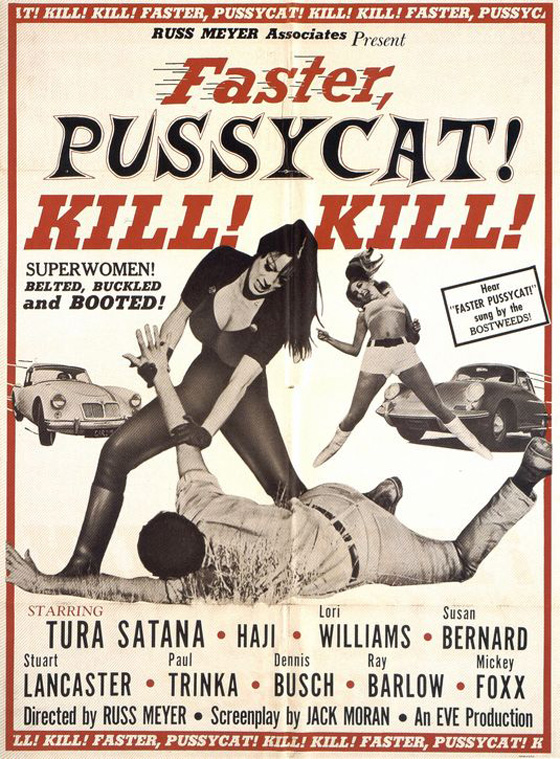

There’s a scene early in Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) which deserves to stand alongside the diner scene from Five Easy Pieces in iconic stature. A bumpkin working the pump at a gas station is making innocuous small talk with Varla (Tura Satana), a raven-haired, giant-breasted femme fatale with a conspicuously unconscious teenage girl in the passenger seat. He finishes his puttering soliloquy on traveling the American highway with: “Yessir, the thrill of the open road. New places, new people, new sites of interest. You know, that’s what I believe in, seein’ America first.” As he’s scrubbing the windshield, his eyes linger on Varla’s Grand Canyon cleavage. She barks at him, “You won’t find it down there, Columbus!” This is Russ Meyer poetry, and it’s all I need in life. Specifically, it springs from the pen of Jack Moran, who also wrote Meyer’s cartoonish burlesque Wild Gals of the Naked West (1962) and would craft equally rich-as-fudge dialogue for Common Law Cabin (1967) and Good Morning…and Goodbye! (1967). Many would argue that Meyer and Moran were the perfect marriage, even better than Meyer’s later partnership with Roger Ebert (Beyond the Valley of the Dolls), whose dialogue pushed the parody into overt Pop Art satire. (As for Meyer’s actual marriage, to his producer and former pin-up Eve Meyer, star of 1961’s Eve and the Handyman – well, that was on the rocks.) Moran marched Meyer’s love of big-breasted women and frenetic, euphoric editing straight into the realm of camp, but with its head held high. His punchy, hilarious script elevated the schlock to Shakespeare (with karate chops). But Meyer couldn’t have produced his first masterpiece without his “pussycats,” the lethal go-go dancers embodied by Tura Satana, Lori Williams, and Haji, who died this past week at age 67. They seduce, they scream their dialogue, they race cars, they kill – and often Meyer, in outright worship, shoots them from a low angle so that they tower, Village of the Giants-style, as powerful idols.

"The Old Man" (Stuart Lancaster), accompanied by his son "The Vegetable" (Dennis Busch), meets pussycats Haji and Tura Satana.

The opening scene depicts the quivering black waves of the soundtrack while the unseen narrator gushes a soliloquy on the film’s two main themes: violence and women. You’d be forgiven to think you’re watching a stranger interlude in Fantasia (1940), or perhaps The Girl Can’t Help It (1956). Then we’re off to the races, specifically the go-go club called The Pink Pussycat, where Satana, Haji, and Williams shake their stuff and crazed men scream, “Go baby, go! Faster, faster!” – as if they have money on this contest. At the orgasmic height we cut to Satana in her car tearing up the Mojave Desert, laughing wildly, and the opening titles with its theme, “Faster Pussycat,” sung by some group called The Bostweeds. One thing is clear: this isn’t just exploitation. This is insanity. Still, no time to take a breath, we move on – to a spontaneous nude swim in a watering hole by the blonde-haired Billie (Williams), which for some reason infuriates Rosie (Haji), who shouts, in an accent not distant from Chico Marx, “Go ahead, sponge, soak it up! I’m-a gonna love squeezin’ you out!” (As Billie dresses, Rosie doesn’t let up: “All right, you washed – now I’m-a gonna spin-dry you!”) All this good-natured go-go-dancer psychosis is interrupted by two young ones driving into the Mojave for some car-racing time trials. Rather quickly, the three pussycats bully the two – Tommy (Ray Barlow) and his bikini-clad girl Linda (Susan Bernard) – which Varla escalates to violence, karate-chopping Tommy to a bloody pulp and then snapping his spine. Taking Linda hostage, the pussycats travel deeper into the Mojave until they encounter a ranch owned by a crazed miser (Stuart Lancaster, Mudhoney), whom they plan to rob, having learned that he’s won a fortune in a settlement following a train accident. But “The Old Man” is as crafty and perverse as Varla’s gang, and plots to capture all four women, assisted by his two sons, a thick-skulled bodybuilder called “The Vegetable” (Dennis Busch, “a piece of mutton, a blob of flesh!”), and the morally conflicted Kirk (Paul Trinka).

Tura Satana as Varla: "You won't find it down there, Columbus!"

As the day wears on, hanky-panky, suggestive corn-on-the-cob-eating, and murders (by switchblade and charging vehicles) ensue. There’s also a bit of dementia: the Old Man’s near-death encounter with a train has left him with a hatred of women (it was a woman that nearly cost him his life on the tracks, you see) – and the Vegetable with a homicidal migraine akin to John Cleese’s in the “Dirty Fork” sketch. “It’s only a choo-choo,” Billie complains when her make-out session is interrupted. “Don’t lose the beat, hon!” The film gets plenty of traction from Meyer and Moran’s crisp portrayal of every character as a particular kind of crazed mess. Varla is described as a beast: “She’s a cold one all right, more stallion than man – more than one man can handle,” the Old Man says. And his oldest son laments – mostly to her chest – “You’re a beautiful animal, and I’m weak, and I want you!” Rosie is apparently in lust with Varla too – or so we gather when we see her weeping as she catches Varla and Kirk in a lover’s clinch (Haji later confessed she didn’t figure it out until Meyer told her, so it hardly informs her performance). Despite her tough demeanor, she gains the most sympathy when she can’t quite bring herself to pull a knife out of the body of one of her fallen friends, fear leading her to ask the Vegetable to do it instead. As for the carefree Billie: “Sometimes I see [Varla] try to figure me. I can’t even figure myself!”

Rosie (Haji) tries to convince The Vegetable to return her knife.

Meyer’s irresistible cocktail of drive-in joy was shot as quickly and efficiently as all his other projects – on the cheap, in the desert, tearing up the pages as he filmed them. He believed strongly that all energy be devoted to the filming, to the extent of prohibiting the cast and crew from indulging in sex until production had wrapped. (Tura Satana ignored that last rule, and got her kicks, much to Meyer’s frustration. No one tells Varla what to do.) Teenage model Sue Bernard (daughter of famed photographer Bruno Bernard, aka“Bernard of Hollywood”), was accompanied everywhere by her stage actress mother, who complained, made demands, and rubbed everyone the wrong way, in particular Meyer and the pussycats. All that resentment found its way on screen, in Varla’s manhandling of Linda, and in her contemptuous sneer. Just as convincing are the pussycats’ relationship to each other and their chemistry as a go-go gang. Exotic dancers Satana and Haji were good friends, with Williams bonding with them for the first time, a dynamic evident onscreen. As with Motorpsycho (1965), also starring Haji, this black-and-white exploitation film featured no nudity, just bare backs and shoulders – unusual for a man who made his name with “nudie cuties” and his photography for early Playboy Magazine. But it was a savvy commercial move, reaching a wider audience – and in retrospect it is his most accessible picture, the obvious entry-point into his lusty filmography, and championed by the likes of John Waters, who declared it one of his favorite films, and Rob Zombie, who screened it on Turner Classic Movies. As with many other Meyer films, any objectification of women becomes irrelevant under his abject worship of these powerful figures – to the extent that the three kick-ass pussycats have become feminist icons, of a kind. Two are gone now, and cinema will miss them, but their legacy lives on in every kick-ass action heroine in the multiplex. R.I.P. Tura Satana (1938-2011). R.I.P. Haji (1946-2013). You were beautiful, and we were weak, and wanted you.