I was a gullible kid, but I always struggled with the concept of Bigfoot. I grew up in California and my family lived along the Pacific Northwest – to top it off, I was born in the 70’s – so it was hard to avoid tales of sasquatch. And some of my early reading memories are books from the library on cryptozoology: The Loch Ness Monster and other lake monsters, mokele-mbembe, yeti, and so on. But while I was intrigued by Bigfoot, and stared hard at fuzzy stills from that Patterson-Gimlin film allegedly depicting Bigfoot striding through the woods and glancing toward the camera, I couldn’t understand how, if it were all true, we hadn’t captured one yet. Surely one of the sasquatch would trip up, get hit by a car, step in a bear trap, or get caught on camera stealing a dumpster from behind a German restaurant? Yet supposedly one did get into a car accident, leaving prints near a ghost town called Bossburg in Washington State in December 1969: the “Bossburg Cripple,” they called it, since one of the footprints resembled a fractured foot. One of the men associated with this find was Ivan Marx, soon to become one of the most notorious characters associated with tales of Bigfoot. A self-described tracker, with his wife Peggy he worked as an animal trainer on Walt Disney’s “True-Life Adventure” nature films, and shot many color 16mm films of animals in the wild before getting himself tied-up in sasquatch hunting. (I find it interesting that the Marxes worked on Disney’s nature documentaries, since those films, though award-winning and groundbreaking, contain many staged or dubious sequences in their attempts to elicit drama and excitement. For 1958’s White Wilderness, lemmings were imported to the non-native habitat of Alberta and herded off a cliff to depict a “lemming suicide.” I am not alleging the Marxes were involved, but the Disney “documentaries” would not measure up to modern standards of non-fiction filmmaking; it was a different time.) Ivan Marx soon produced some 30 seconds of 16mm Bigfoot footage in 1971, which he claimed to have shot the prior year. Peter Byrne, then director of the California Bigfoot Project, briefly hired Marx, and the group agreed to purchase a sealed canister of his master footage for $25,000, before some investigation of the evidence uncovered some troubling inconsistencies in Marx’s story, and Marx skipped town, leaving them with a canister that, luckily, they never actually paid for, since it contained only Mickey Mouse cartoons. (Byrne tells the whole fascinating story here.) Nevertheless, Marx continued to hunt Bigfoot, and edited his footage – including longer shots of the sasquatch – into a 74-minute film called The Legend of Bigfoot (1976).

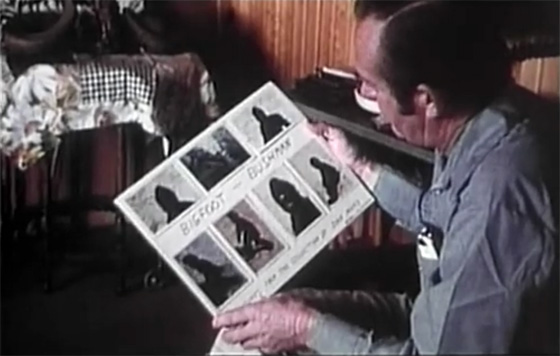

Ivan Marx examines stills from his Bigfoot footage in "The Legend of Bigfoot."

It barely qualifies as a movie, and certainly not as entertainment. Taking its lead from the True-Life Adventure films, Marx’s “documentary,” directed by Harry Winer (SpaceCamp), collects reels and reels of his older nature footage padded with new footage of our “last of a dying breed” tracker following a theoretical sasquatch migration trail into Canada and finally north of the Arctic Circle, to his breeding grounds. Marx narrates, overemphasizing his initial skepticism about the existence of Bigfoot so that he can guide us gradually toward more outlandish theories, and his quest for evidence to convince non-believers of their truth. Since most of the footage lacks a soundtrack, we’re dependent on Marx’s voice to sell the excitement of his work: “The Lava Beds, Modoc, California… A track, centuries old, preserved in the lava. My theory was working! But I wondered how Bigfoot survived the violent eruptions that brought the lava rock…” At every opportunity he squeezes in his unrelated nature footage, including one preposterously harrowing scene of two ground squirrels. After the “lovers” frolic in the road to a medieval jig, one is struck by a car. While the squirrel tries to drag its injured companion through the dirt, Marx cuts to other shots of squirrels “looking on.” A hawk circles overhead, ready to strike. For a good minute, the soundtrack entirely disappears, until the squirrels have reached safety. Marx finally concludes, “Nature was reminding me of her basic law: survival. This same will to survive must have somehow kept Bigfoot going throughout all these years.”

Ivan Marx introduces "The Legend of Bigfoot."

Marx’s conviction that the sasquatch are migrating north provides for some convenient remedies to the whole lack-of-evidence problem. As he tells us, over shots of giant chunks of glacier-ice dropping into the ocean, “The constant movement of the glaciers could either crush the [Bigfoot] remains or wash them out to sea.” Of course – the sasquatch, clumsier than polar bears, are falling between cracks in glaciers. At one point, following the clues of some helpful Eskimos, he sets up walkie-talkies in little stone cairns placed at strategic locations and waits inside a tent in the middle of the wilderness, oddly confident that Bigfoot will show. Sure enough, in the night his wife Peggy sees what she at first thinks are car headlights approaching from a distance, but are in fact “shining eyes.” It’s unclear whether the footage which accompanies this is intended to be a reenactment, but I hope so, because it’s a pretty terrible special effect (and, indeed, looks like two car headlights hovering over a low black mound; if Bigfoot’s eyes can really shine this brightly, it must make it awfully difficult for him to hunt at night). When Marx finally gives us the goods – reaching a particular river where he expects Bigfoot will show, building himself a little nest, applying ammonia to hide his scent, and breaking out the binoculars – he provides so much footage of big and small sasquatch cavorting in and around the water that his credibility floats far downstream. They look like people in suits of black fur. Skeptics believe it’s his wife Peggy who wore the costumes. Marx proclaims, “I now know why the Eskimos call Bigfoot ‘the king of the animals,'” and expresses how his footage backs up his latest scientific discovery: that the creatures aren’t carnivores, and shouldn’t be feared. Though increasingly dismissed by Bigfoot enthusiasts, Marx went on to make two more films, In the Shadow of Bigfoot (1981) and Bigfoot: Alive and Well in ’82. He died in 1999.

In "Bigfoot," Joi Lansing is kidnapped by love-hungry sasquatch.

The 70’s saw a surge of sasquatchsploitation, and why not? It’s easy enough to put a guy in an ape suit and have him terrorize some actors in the woods. Bigfoot (1970) was early out the gate, and had the promising idea of putting the creature up against both a biker gang and John Carradine, though the film itself doesn’t quite live up to the concept. The film opens with 41-year-old model/actress Joi Lansing (Touch of Evil) crashing her small-engine plane over the California mountains. No sooner has she stripped down to skimpy clothing than she gets carried off by Bigfoot, kicking and screaming. Tied to a tree on an obvious set, she soon has guests, including another buxom gal, and Bigfoot hunters Carradine and John Mitchum (Dirty Harry), who fill lots of screen time with their “comic-relief” interplay. The movie feels a bit like Eegah! (1962), and doesn’t get much further than sasquatch carrying off people, tying them to rather fragile-looking trees, and stomping around, grunting, as though there’s a black monolith nearby. Occasionally we cut away to a local diner or sheriff’s office where colorful locals use up as much running time as they can. In the climax, Bigfoot, who wants to breed with Lansing, is buried under rubble after one of the bikers lobs sticks of dynamite at him. Carradine paraphrases King Kong, muttering, “It was beauty did him in.” (Not really. It was the dynamite.) The homage to Kong extends to the opening credits, which boast, in giant typeface, “And Introducing James Stellar as ‘Bigfoot,’ the Eighth Wonder of the World.” I enjoyed the groovy score (by Richard Podolor, whose resumé includes producing Three Dog Night’s “Joy to the World”), but the film isn’t terribly thrilling. The ending credits proclaim, “All outdoor sequences were actually filmed on various mountainous locations where ‘Bigfoot’ has been documented and reportedly seen by several individuals,” but the film’s heart is really with B-movies of decades past.

Some bikers take their time coming to the rescue in "Bigfoot."

Out of the 70’s came the sasquatch sleeper hit The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972), followed by Return to Boggy Creek (1977) and Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues (1985, the “official” sequel from original Boggy Creek director Charles B. Pierce). The decade also gave us documentaries like Bigfoot: Man or Beast? (1972) and In Search of Bigfoot (1976), and thrillers like Sasquatch: The Legend of Bigfoot (1977) and Revenge of Bigfoot (1979). The Leonard Nimoy-hosted TV series In Search Of…, which I watched constantly as a child, got to Bigfoot as quickly as its fifth episode (in April, 1977). Artist John Byrne created a Marvel Comics character called Sasquatch (who is one) for the Canada-based superhero group Alpha Flight, debuting in the pages of Uncanny X-Men in 1979. Kids also had the TV series Bigfoot and Wildboy (1977), which surely has one of the greatest opening title sequences ever:

Several years ago I attended part of a “Bill Rebane Film Festival” in Madison, Wisconsin, spotlighting the work of the local director behind films like Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake (1975), and The Alpha Incident (1978). Introducing the festival were Mike Nelson and Kevin Murphy from Mystery Science Theater 3000, which featured Rebane’s best-known film, Giant Spider Invasion (1975), in one of its episodes. (All I remember from their introduction is that some problems with the video meant the screen behind them was projected in a solid blue color. Murphy deadpanned, “Ladies and gentlemen, Derek Jarman’s Blue.”) Before the screening of a documentary on Rebane’s career (directed by his wife), I wandered past a display in the lobby containing memorabilia from his films, including stills from something called The Capture of Bigfoot (1979). The film intrigued me with its images of a Gilligan’s Island-style cavern and a man in an Abominable Snowman suit standing inside a cage. The documentary barely touched on the film, if it mentioned it at all, so I was left wondering – and finally, years later, I’ve caught up with it.

The creature in Bill Rebane's "The Capture of Bigfoot" takes its vengeance on some snowmobiling poachers.

Truth be told, as the third part of this Bigfoot marathon, the film comes across quite well; that is, at least by comparison to what we’ve just watched, The Capture of Bigfoot passes the time fine, and is competently made (high praise, I know). The film takes place in and around a snowy Midwestern town in which a local Indian legend of the “Arak” proves to actually be a Bigfoot, though one of the albino variety, apparently, since it looks like a yeti. Poachers, led by the evil Olsen (Richard Kennedy, The Buddy Holly Story), first shoot one of its adorable pubescent offspring in the chest, then capture an adult and lock it up in the woods. Officer Garrett (Stafford Morgan, Cleopatra Jones) sympathizes with the rare creatures and goes to free Bigfoot with a blowtorch. That’s about it, but The Capture of Bigfoot has a few things going for it. Unlike Bigfoot (and, let’s face it, The Legend of Bigfoot), the sasquatch suits are pretty nifty, to such an extent that I’m mystified that Rebane doesn’t use them more. In one scene, Bigfoot lifts a snowmobile and throws it at the hunters who murdered his son, and if the movie was all this, it would be a drive-in classic. Rebane does manage a few amusingly homegrown action scenes, including a snowmobile chase that would not make James Bond jealous, and a nighttime car chase along snowy streets, including a car flip. What makes this all so damn charming is that it’s filmed in small-town Wisconsin, principally Gleason, northwest of Green Bay. (Gleason is just south of Rhinelander, which takes great pride in its own legendary monster, the Hodag.) And this movie really captures the feel of northern Wisconsin in the dead of winter, with its loud, nondescript diner where Garrett’s girlfriend works and all the locals gather to gossip, to the glowing Old Style Beer sign hanging over the door of the bar where a lynch mob gathers – even to the image of two young boys hunting rabbits with real rifles and real bullets in the snowy woods. Yep, this is definitely 1979 Wisconsin. What comes across is the joy of locals enthusiastically shooting a Bigfoot movie, probably between Packers games, and when they blow up a car in a fiery explosion, it’s easy to cheer. (As usual, the Rebane clan gets in on the action. The credits list Randolph Rebane as “Little Bigfoot.”) So yes. This is what I want out of a Bigfoot movie. Rebane got it right.