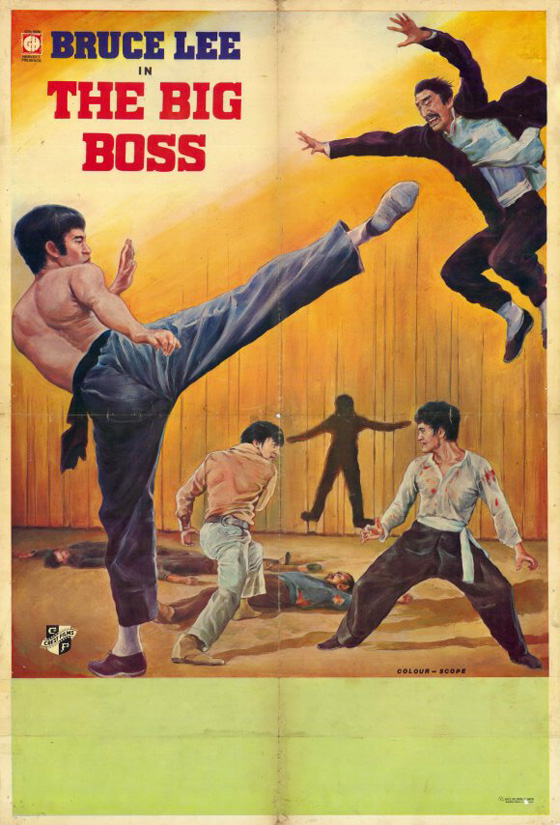

Bruce Lee died in Hong Kong forty years ago this past July, suddenly and tragically (doctors ruling it a cerebral edema; conspiracy theories still percolate), a rich and pioneering career ahead of him that would never be fully realized. For my money, he showed more promise than James Dean, being not just a charismatic screen personality but also a tireless entrepreneur (he started a martial arts school shortly after moving to America) and innovator (developing the Jeet Kune Do technique from his research into fencing and boxing). Through his work in TV – The Green Hornet, Longstreet, Batman – and those handful of starring roles in film, he helped combat Asian stereotypes, and left behind a significant legacy on screen, though not nearly enough. His biggest hit, Enter the Dragon (1973), was released days after his death; there’s no telling what he could have achieved had he lived to enjoy that success. Regardless, interest in the martial arts skyrocketed following his passing. His earlier films were re-released, sometimes retitled, and played drive-ins and grindhouses throughout the decade. His signature moves – and bestial facial expressions – were memorized and imitated, and posters of Bruce Lee adorned thousands of bedrooms and gyms from coast to coast. But before Lee invaded America, he conquered the East, a stepping-stone to lead him back to Hollywood with greater cachet. The San Francisco-born Lee was first lured back to Hong Kong, the city where he was raised, after learning that The Green Hornet was enjoying success as The Kato Show. He signed a two-picture contract with the new production company Golden Harvest, which was behind films like Zatoichi Meets the One-Armed Swordsman (1971) and The Angry River (1971, with a young Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung), and which was founded by Raymond Chow and Leonard Ho, formerly of the Shaw Brothers studio. The Shaw Brothers had offered Lee a deal too, but Golden Harvest seemed to have a better appreciation for his potential. For The Big Boss (1971), Lee was intended to have a supporting role. Instead, his part was swapped with co-star James Tien’s when it was apparent that Golden Harvest had a dragon on their hands.

Bruce Lee contemplates revenge after the slaughter of his family.

The Big Boss is written and directed by Lo Wei, an actor who also directed martial arts films such as The Brothers Five (1970) and, years later, helped further Jackie Chan’s persona as an action star with Shaolin Wooden Men (1976). The original Chinese title translates as The Big Brother from Tang Mountain, but The Big Boss was also released as King of the Boxers, before it became Fists of Fury, not to be confused with his next film, Fist of Fury (1972), which then became The Chinese Connection, and my head hurts. Though not as entertaining as the pulpy Enter the Dragon, much of the appeal of The Big Boss lies in its stripped-down simplicity. It’s a film about violence and revenge, and nothing more. Lee plays the pacifist Cheng Chao-an, who, in the film’s opening, arrives off a boat from China to stay with his extended family in Thailand. To remind himself of his vow of non-violence, he wears a jade necklace; whenever he’s tempted to break out his fists, he touches the necklace, and a gentle music-box jingle plays on the soundtrack. We know it’s a matter of time before that vow is broken and we don’t have to listen to that damn music box anymore, but the slowburn to that catharsis has a nice interruption when his cousin Hsu Chien (Tien) gets in a scuffle with a local gang, and Lee casually busts some heads while cousin’s back is turned, all without breaking a sweat. In that quick fight scene, the charismatic Lee becomes a star – in just a few audience-pleasing moves he’s already overshadowed the athletic, handsome Tien.

Lee and his co-workers at the ice factory confront a gang of dope-smugglers.

Lee goes to work with his cousins at an ice factory, where giant slabs of ice are handled with menacing-looking tongs before they’re sent sliding down wooden chutes, setting up an inevitable fight setpiece – and we’ll get two of them at the ice-works before the film is through. We quickly learn that the factory is a cover for a drug-smuggling operation, the bags of dope being frozen within the ice blocks, all of this run by Hsiao Mi, “The Big Boss” (played by the film’s fight choreographer, Han Yin-chieh). Those who discover the nature of the organization are taken out if they don’t fall in line, most dramatically when two of Lee’s cousins, one of them Tien, are killed in a brutal fight in the yard at Hsiao Mi’s house. When a large-scale fight breaks out at the factory, Lee’s necklace is broken, and the dragon is loosed. To gain control of the workers once more, Hsiao Mi makes Lee the new foreman, a promotion that comes with alcohol and prostitutes (breaking the heart of Lee’s love interest, played by Maria Yi, who spends most of the film weeping for one reason or another). Lee finally discovers both the heroin and the bodies of his cousins hidden in the ice, leading to a fight in which he kills Hsiao Mi’s thuggish son. In retaliation, Lee’s entire extended family is slaughtered, including a young boy. Enraged, he heads off to rescue Maria Yi and confront the Big Boss.

Lee pays the price for enacting his revenge.

Though the fight scenes are more straightforward than modern martial arts films (imagine what Jackie Chan’s Buster Keaton stylings could have done with all those ice props), Lee brings a ferocity and brutality that is arresting to watch. The fights become increasingly bloody, leading to a finale in which he actually punctures Hsiao Mi’s chest with his fingers. (Following its initial Hong Kong release, the film was heavily censored for its shots of explicit gore.) Han Ying-chieh resisted Lee’s newfangled moves, but his assistant, Lam Ching-ying, argued in favor of Lee’s fighting approach and formed a close bond with the actor (Lee even bailed him out of jail during the filming), going on to work with the star for the remainder of his film career; in the ensuing years, Lam would become a celebrated action choreographer, as well as a film star in his own right, thanks to his recurring role in the popular Mr. Vampire series. The Big Boss remains a landmark film in martial arts cinema, reinvigorating the genre in China and stoking interest in the States for all things Kung Fu. The film was recycled and revived many times; one notorious Cantonese cut even features bits of prog rock music (including songs by Pink Floyd and King Crimson), and various official and bootleg cuts in circulation feature different edits of the soundtrack (by composers Wang Fu-Ling and Peter Thomas), the dialogue (dubbed or Cantonese), and the fight scenes. Bruce Lee’s influential film has been fully appropriated by the masses.